Politics

16:17, 05-Jul-2017

China issues 15 more registration certificates for overseas NGOs

When China passed a law in April 2016 requiring overseas non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to secure approval from authorities before they are allowed to operate on the Chinese mainland, concerns swarmed around the requirements needed to get the go-ahead.

Accusations were also rife that Beijing was trying to stifle civil society and restrict its members’ activities, despite repeated reassurance from relevant Chinese authorities. But since the law came into effect on the first day of 2017, registration of foreign NGOs has been swift and smooth, with over 84 organizations receiving their registration credentials across the country.

Last week, Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau issued the latest batch of registration certificates and chief representative certificates to the Beijing offices of 15 overseas NGOs, granting them legal status and green-lighting their operations.

The not-for-profit entities are from Hong Kong and a number of foreign countries, namely the US, Switzerland, Japan, and South Korea. Their work covers a host of fields, ranging from environmental protection (Environmental Defense Fund) and poverty alleviation (Caterpillar Foundation) to copyright of a musical work (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry) and trade (World Trade Centers Association).

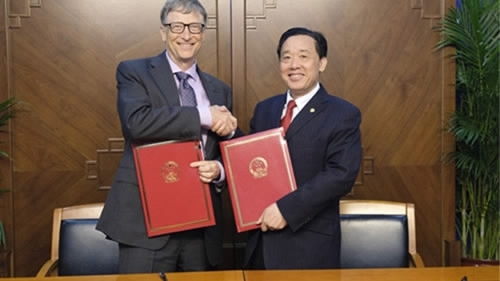

The awarding of certificates came after Chinese authorities granted similar approvals to the offices of four German NGOs in the capital in May, and 20 offices of NGOs from Hong Kong, Taiwan and foreign countries, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the World Economic Forum and Paulson Institute in January.

A total of 62 overseas NGOs have succeeded in setting up representative offices on the Chinese mainland, including in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Wuhan since January 1, 2017. Another 150 organizations are going through the registration procedure.

To protect and inspect

The Law on the Administration of Activities of Overseas Nongovernmental Organizations in the Mainland of China was adopted during the bi-monthly session of the National People's Congress (NPC) Standing Committee on April 2016, following three readings that saw a handful of previous restrictions eased or removed.

Poverty alleviation is one of the fields of overseas NGOs on the Chinese mainland. /VCG Photo

Poverty alleviation is one of the fields of overseas NGOs on the Chinese mainland. /VCG Photo

The law aims to provide a clear code of conduct for NGOs from outside the Chinese mainland, conferring legal status and ensuring the protection of their rights while keeping them in line with the country’s rules.

The law “will help to protect their (NGOs from outside the Chinese mainland) legitimate rights and interests and promote exchange and cooperation, while also helping to strengthen China's law-based oversight and regulation and safeguard China's national security and public interests,” read the report on the work of the standing committee of the NPC delivered at the Fifth Session of the Twelfth National People's Congress on March 8, 2017.

Groups of the civil society are prohibited from compromising the country’s unity, security or ethnic solidarity, engaging in commercial and political activities or illegally sponsoring religious activities, Xinhua News Agency reported, noting that their certificates could be revoked if they were found guilty of misconduct.

Meanwhile, their legal operations are also protected by law.

“Governments at all levels will be obligated to accommodate the legal operation of overseas NGOs, providing necessary assistance and service. The NGOs will enjoy preferential tax policies,” Xinhua noted.

Dynamic drafts

Before coming into effect, China’s public security authorities solicited public opinion about the draft manual and held on October 2016 a seminar in Shanghai which was attended by representatives of nine overseas NGO offices and trade associations in the city, including the United States-China Business Council and China-Britain Business Council, where participants gave their feedback, placed their remarks and voiced their concerns.

Authorities also responded to more than 12,000 questions from over 780 overseas NGOs.

The adopted law saw noticeable changes from the original and the second drafts pertaining to its scope, the hiring procedure and permission for temporary activities of overseas NGOs, among other areas the revision had touched upon.

The breadth of the law was narrowed down to exclude foreign schools and hospitals, and research and academic institutions focused on natural science, engineering and technology.

The law also nixed a provision that limited offices of overseas NGOs on the Chinese mainland to one location, and crossed out the five-year operational limit on representative offices. Previous restrictions on staff and volunteers were also removed.

The US-China Business Council is among the 62 NGOs who set up offices in China. / USCBC Photo

The US-China Business Council is among the 62 NGOs who set up offices in China. / USCBC Photo

The adopted guidelines also replaced the permit for NGOs wanting to operate temporarily on the mainland with a notification by a local co-sponsor presented 15 days before the start of the program.

Anxieties and antidotes

Despite the adjustments, concerns remained about certain provisions of the law in the lead-up to January 1.

Some described as “worrisome” the broad powers placed in the hands of law enforcers to supervise and regulate the sector, including interviewing representatives and executives if suspected of breaking the law and asking local partners to terminate cooperation programs.

However, Hao Yunhong, director of the overseas NGO management office of the Public Security Ministry, said authorities will ensure an “open, inclusive and transparent attitude” when dealing with overseas organizations.

“The police have not been handed unrestricted power, and systems will be in place to assure accountability and, should they fail in their duty, suitable punishments,” read an opinion piece titled “No need to overreact to China's overseas NGO law” published by Xinhua last June.

Another issue of apprehension was the obscurity in a specific provision that requires organizations to choose a government department to be their “business competent authority” prior to applying for credentials.

Director Hao said that a detailed protocol was being worked out which would produce a list of fields and activities open to NGOs on the Chinese mainland and the authorities in charge of them.

Over half a year after its introduction, the increasing number of overseas NGOs that are receiving their credentials reflects the careful planning that has been put in place. It also showcases the ability of authorities to take concerns into account and act upon constituencies' feedback to deliver their promise of providing efficient services to overseas not-for-profit organizations while they get regulated, supervised and protected.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3