Business

19:48, 05-Dec-2017

After hot debate, US tax bill a boon to businesses

CGTN

The sweeping tax reform package adopted by a slim margin of 51-49 early Saturday by the Republican-controlled Senate has sparked fierce debate among economists.

It also has yet to be reconciled with a separate version passed by the House of Representatives.

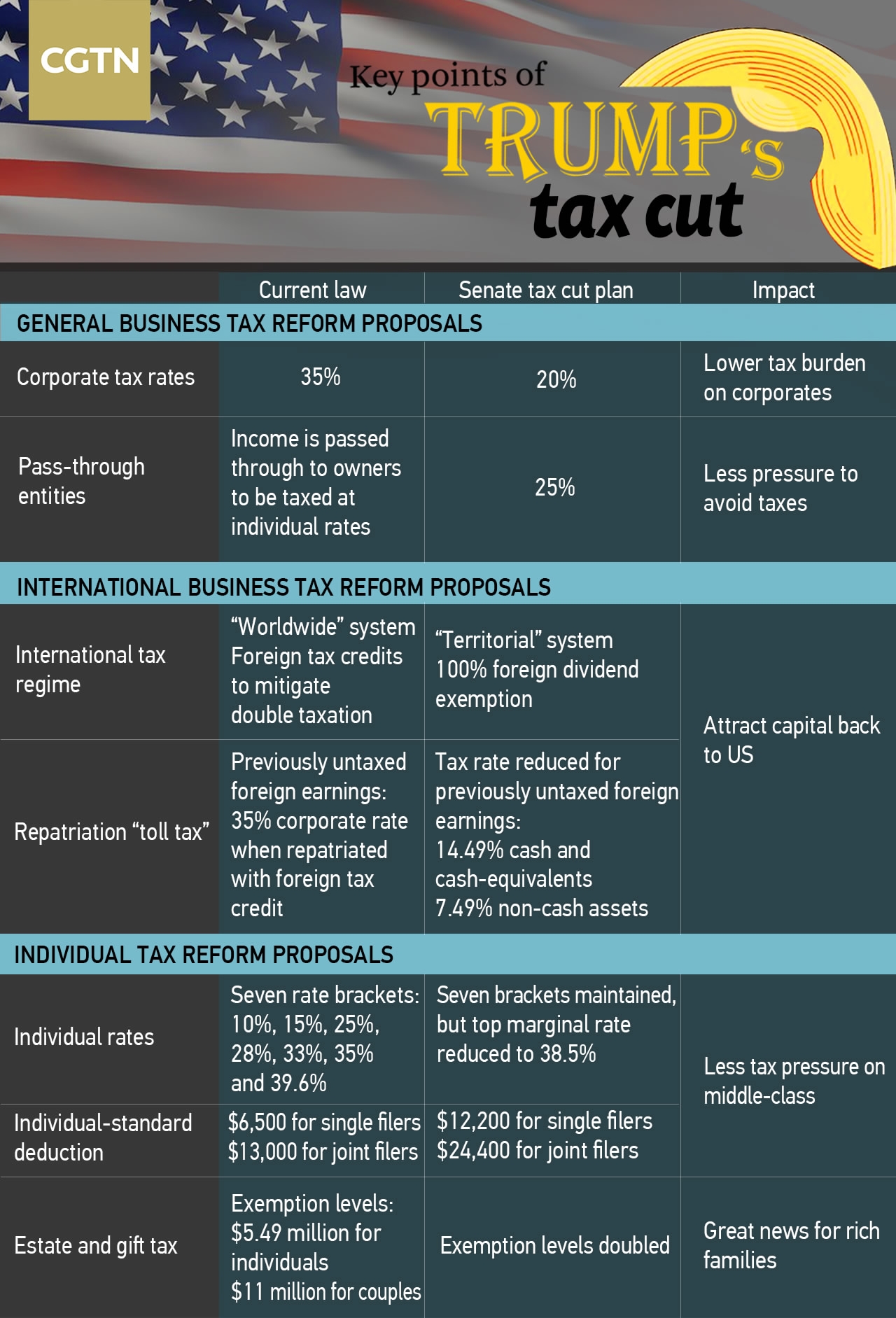

But the proposal's main planks included a reduction in corporate tax rates from 35 to 20 percent, increasing some deductions for individual taxpayers while eliminating many others and reducing taxation on partnerships.

Balloon the debt

The White House portrays the new tax package as the largest tax cut in US history and says it is aimed at spurring growth and producing higher wages and corporate profits while encouraging tax-shy companies to repatriate their wealth.

One of the proposal's main boosters, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, recently touted a letter from nine economists who asserted that the first comprehensive tax overhaul in three decades would lift annual GDP growth by 0.3 percent over 10 years.

But a University of Chicago study found that among 38 economists, the overwhelming majority doubt growth will increase and nearly all believed it would balloon the national debt.

The Joint Committee on Taxation, a nonpartisan committee which estimates the cost of tax policies, also found Thursday the bill now passed by the Senate would add 1 trillion US dollars to the deficit.

Many economists argue that this kind of stimulus has limited impact when the economy is growing at its full potential pace.

Disagreements have at times turned personal, with former Labor Secretary Robert Reich, a Democrat, writing in an opinion piece on Wednesday that Mnuchin was either a "fool or a knave," accusing him of lying about the supposed benefits of the tax overhaul.

Is now the right time?

Reich cited the findings of the Tax Policy Center, according to which over a decade most of the proposal's benefits are likely to go to the wealthiest one percent of Americans while the upper middle class would likely face a higher tax burden and the poorest would see only small tax cuts.

But according to Douglas Holtz-Eakin, one of the economists who signed the letter cited by Mnuchin, said the modified new tax code aims to boost production and supply, rather than demand.

Entrepreneurs are among the first who stand to gain, with corporate tax rates falling as much as 15 percentage points, supposedly down to a level in line with those in other developed countries.

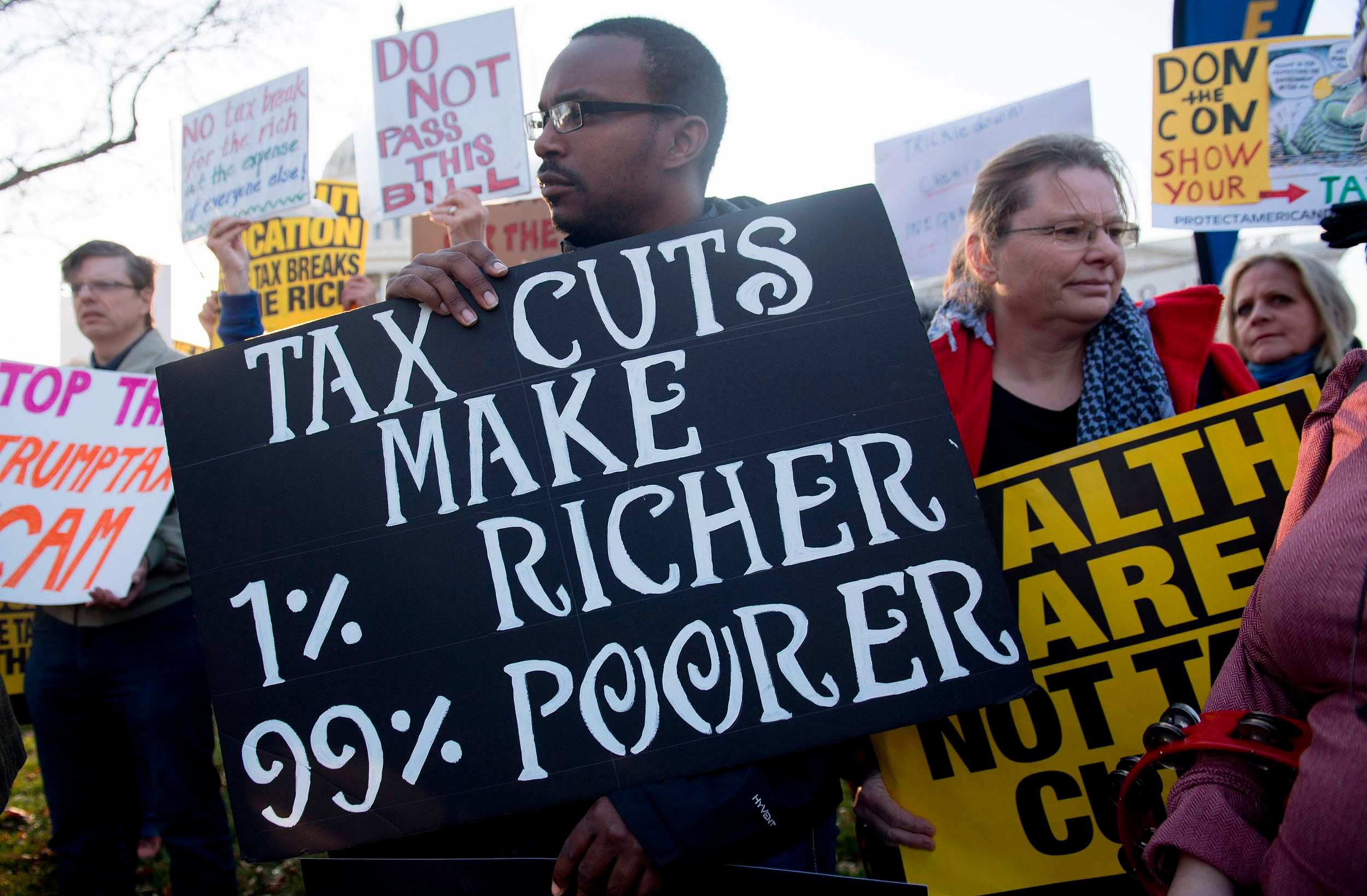

Demonstrators against the Republican tax reform bill protest outside Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, November 30, 2017. /VCG Photo

Demonstrators against the Republican tax reform bill protest outside Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, November 30, 2017. /VCG Photo

But US companies have long benefited from tax deductions that brought their effective tax rate down to around 21 percent.

Another boon for the business world: partnerships and other so-called "pass-through" companies whose profits are enjoyed directly by their owners – and which account for half of corporate revenue and 90 percent of small businesses – will see steep tax cuts.

Multinational companies also will be encouraged to repatriate their profits at a preferential tax rate.

According to Holtz-Eakin, these changes are all incentives for innovation and investment that will drive productivity in the US.

However, as White House economic adviser Gary Cohn found while attending a business conference recently, many companies plan to use excess cash from the tax cuts to increase their dividend rather than invest in equipment or hire more workers.

President Donald Trump's administration argues that wages should rise after having stagnated for decades when accounting for inflation.

Holtz-Eakin said productivity gains should make hiring workers more profitable and cause companies to compete for available labor by offering higher salaries.

Others call the timing of such a tax overhaul into question, given that the world's largest economy is already close to full employment and the Federal Reserve is poised to pounce on any sign of inflation by raising interest rates.

Lloyd Blankfein, the CEO of Goldman Sachs, expressed similar doubts last month in an interview with Bloomberg.

"I can't say this is the moment where you want the most fiscal stimulus in the market, when we’re mostly at full employment, when GDP last registered at 3 percent," he said.

"I don’t know that this is the moment that you provide the biggest stimulus."

Source(s): AFP

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3