Heroin is one of the most addictive of all drugs, and there are few places in Asia where it is as pure, cheap, and readily available as in northern Myanmar. Myanmar is now one of the largest consumers of this illegal narcotic in the world -- and it is grown right in its own backyard.

In Myanmar's Shan state, vast poppy plantations supply Asia with 80 percent of its heroin. Opium cultivation there was stopped in 2006. But almost a decade later, a combination of civil war and poverty has driven farmers back to cultivating the crop that feeds a seemingly insatiable global demand.

Myanmar's vast poppy plantations in Shan state are said to supply 80 percent of the world's opium. /CGTN

Myanmar's vast poppy plantations in Shan state are said to supply 80 percent of the world's opium. /CGTN

Today, some 300,000 families grow opium in the state, according to official estimates.

Growing poppies in Myanmar is illegal, but Pee Pilu says he has no other choice.

"I personally think I have made the wrong decision," he tells Assignment Asia. "But if we didn't grow opium, I have no idea how we could make a living."

Even with the choice of other crops, many farmers in Myanmar's Shan state choose opium because of its huge returns. /CGTN

Even with the choice of other crops, many farmers in Myanmar's Shan state choose opium because of its huge returns. /CGTN

Saw Gum, another opium farmer, says he has tried growing other crops before. "But I couldn't feed my family on that," he adds.

According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (ODC), poppy cultivation in Shan state has been growing in recent years.

Myanmar's vast poppy plantations in Shan state are said to supply 80 percent of the world's opium. /CGTN

Myanmar's vast poppy plantations in Shan state are said to supply 80 percent of the world's opium. /CGTN

"Myanmar is still a country with a lot of internal conflicts," says Jochen Wiese of the UNODC. "It's not controlled by efficient state institutions to get modernized."

In the neighboring state of Kachin, one gets a vivid picture of how opium has destroyed lives and shattered dreams in Myanmar. Beneath the state's picturesque scenery is a dark undercurrent of massive poverty and opium addiction.

In the town of Myitkina, community leaders say 6 out of 10 people are using drugs. The problem is so widespread that leaders have declared a major heroin epidemic in the town.

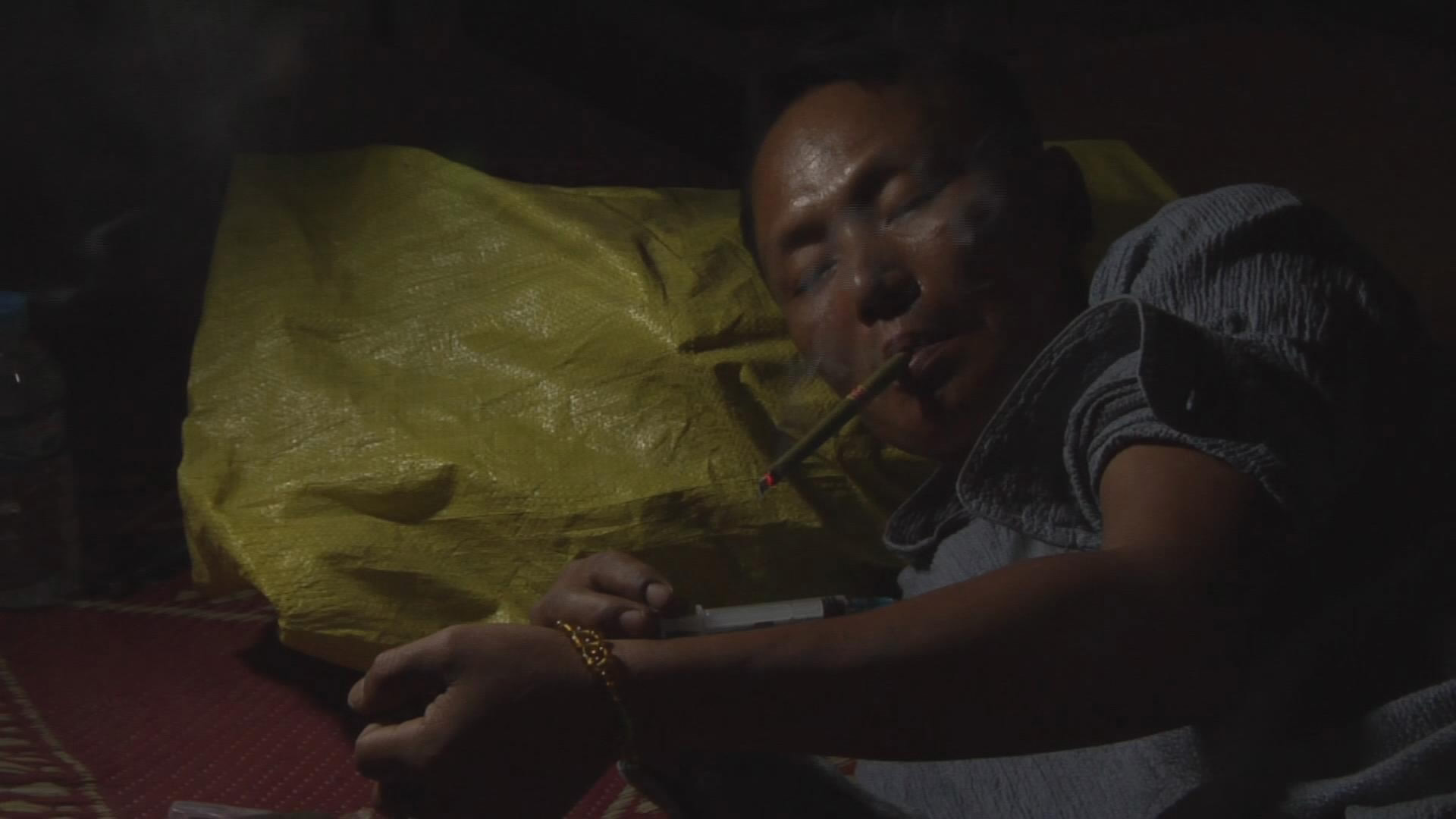

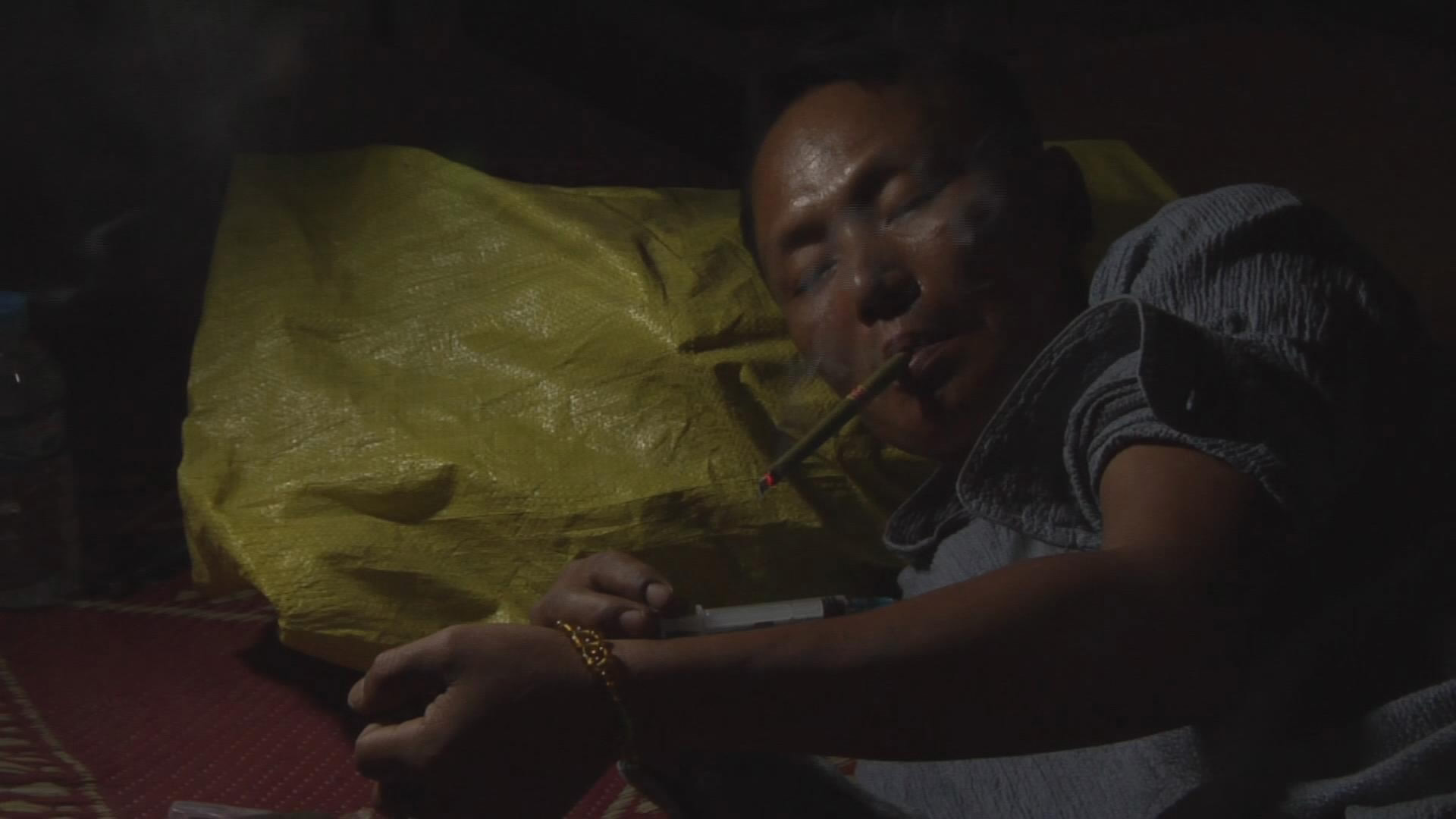

Footage obtained by Assignment Asia shows residents using drugs, illustrating the problem's magnitude.

For many people, a day starts with a cup of coffee. But for Zau Lay and his friends, it begins with a hunt for heroin.

Opium cultivation in Myanmar has grown in recent years despite government efforts to stop it and attempts by groups like the UN Office of Drugs and Crime to introduce other crops. /CGTN

Opium cultivation in Myanmar has grown in recent years despite government efforts to stop it and attempts by groups like the UN Office of Drugs and Crime to introduce other crops. /CGTN

"It is almost essential and a necessity," Zau Lay says. "I feel very disappointed with myself for becoming a slave to this substance."

Hawng Noi had high hopes for her three children. She believed they would help the family get out of poverty, and one of them even planned to work abroad.

Hawng Noi is a resident of Myitkina in Kachin state, where community leaders have declared a heroin epidemic. Her three children all died after becoming addicts. /CGTN

Hawng Noi is a resident of Myitkina in Kachin state, where community leaders have declared a heroin epidemic. Her three children all died after becoming addicts. /CGTN

But her eldest son became a heroin addict and died at 25. Her second son also got addicted and died years later, followed by her daughter, who contracted HIV before passing away.

"I cannot believe how much I had to sacrifice, my sons and daughters, all because of this nasty drug," she says.

Myanmar's Kachin state only has a handful of government-run rehabilitation centers. And so most of the time, religious ministries fill the gap.

At a Christian rehab facility, patients have a daily routine of songs and prayer.

Officials at the facility admit their efforts and resources are not enough. For one, they could not offer proper medical treatment. Addicts seeking treatment spend time in a prison-like room, where their main weapon is religion.

The risk of relapsing is high, officials say. Partly because of unemployment in the region, rehab leader Rajah says as many as 95 percent of their patients relapse after leaving the facility.

Rajah says Myanmar's government needs to do more to deal with the country's drug crisis.

Addicts seeking treatment spend time in a prison-like room, where their main weapon is religion. /CGTN

Addicts seeking treatment spend time in a prison-like room, where their main weapon is religion. /CGTN

"We are infuriated at the lack of help," he says. "But we try harder and harder to succeed."

Global pressure has led Myanmar to exert greater effort in tackling the problem. For more than a decade it has worked with its neighbors Thailand, Laos, and China to strengthen anti-drug law enforcement.

When opium is being cultivated in the backyard, however, the flood of heroin to the front door--and beyond--is inevitable.

Still, groups like the UN continue to encourage farmers to grow other crops. In Shan state, the UNODC has helped people cultivate rubber and coffee.

"We try to help them not only to match ... the poppy opium economy, but also to get them out of poverty," the UNODC's Jochen Wiese says.

For now, however, Myanmar's poppies stand tall, oblivious to the death and destruction it causes at home and abroad.

(Reported by Dusita Saokaew, written by Ryan Chua)