Opinions

10:09, 12-Dec-2017

Opinion: How one journalist changed the Nanjing story throughout the world

Guest commentary by Joel Schalit

When Iris Chang committed suicide in 2004, it was like a bomb dropped on American newsrooms. The 36-year-old journalist and author of the 1997 best seller, The Rape of Nanking, had single-handedly elevated Japanese war crimes during the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-1945), to a topic of mainstream discussion in the United States.

Why they had not been investigated to that point left many journalists and historians in the US feeling as though they’d failed. From the Nazi genocide to the killing fields of Cambodia, few publishing cultures had crusaded harder to expose human rights crises than those in America.

Undated file photo shows women and children killed in airstrikes by Japanese invading troops in China. During the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, around 2.2 million Chinese children were killed or injured by Japanese invaders. /Xinhua Photo

Undated file photo shows women and children killed in airstrikes by Japanese invading troops in China. During the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, around 2.2 million Chinese children were killed or injured by Japanese invaders. /Xinhua Photo

Though many scholars criticized Chang’s book, which brought to light the 1937 massacre in Nanjing, in which over 350,000 civilians were killed by Japanese troops, there was no disputing the fact that Americans had ignored Japanese transgressions in China in favor of focusing on those that took place in Nazi-occupied Europe.

For a country with substantial Chinese and Japanese populations going back to the 19th century, it was an especially problematic subject to bypass – especially during the first three decades of the Cold War, as America’s cadre of Asia analysts obsessed over the figure of Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution, and the Tiananmen Square crackdown, instead.

Anti-Communism played an obvious role. China had actively opposed American policy in Southeast Asia and Korea for over two decades, and had been allied with the former Soviet Union. The 1972 rapprochement between the United States and China had little cultural impact in the US, due, in no small part, to the perpetuation of the East-West conflict for another two decades.

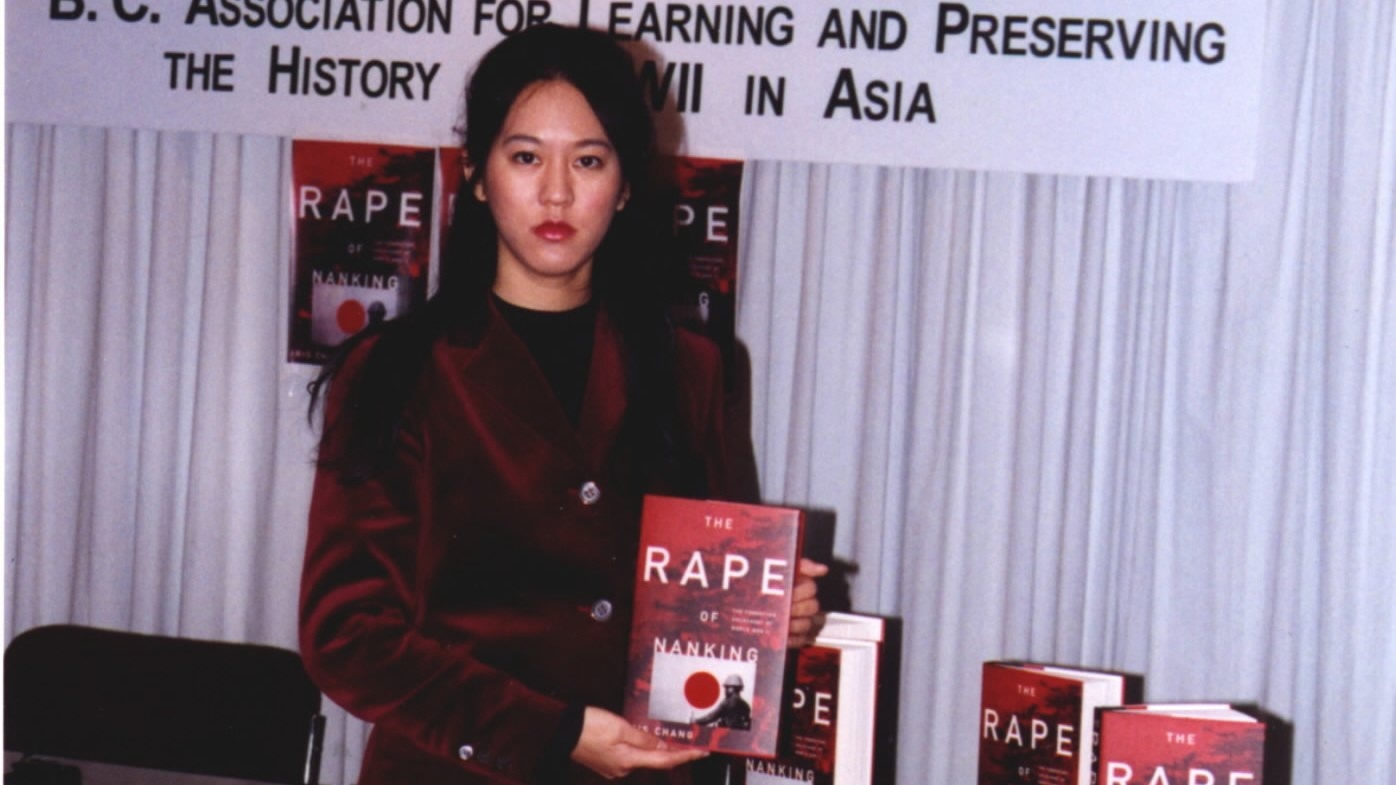

Iris Chang with her books. /CCTV Photo

Iris Chang with her books. /CCTV Photo

In its own small way, Chang’s book about the Nanjing massacre was the first sign of normalization between the two countries. Published six years after the collapse of the former Soviet Union, a Chinese-American journalist had summoned up the courage to write a book redirecting public attention to human rights violations which had preceded the Communist era.

As an Israeli-American journalist living in San Francisco’s other Chinatown at the time – the lesser-known Inner Richmond neighborhood – I was always on the lookout for ways of getting to know my neighbors better than just going out for dim sum. The controversy that had erupted over The Rape of Nanking was the perfect entry. It smacked of Holocaust denial.

Such connections are especially rare for Jews and Chinese, who, in the United States, have few political experiences that bind them other than that they are over-represented minority groups in America’s middle class.

Identifying with her on the basis of shared wartime persecution was an especially profound point of contact for me, a Jew of European heritage. Chang was a granddaughter of Nanjing massacre survivors. My parents’ generation, in France, was full of Holocaust survivors.

People attending the memorial service to Iris Chang on Nov. 9, 2014, at the Gate of Heaven Catholic Cemetery in Los Altos, California. /People’s Daily Photo

People attending the memorial service to Iris Chang on Nov. 9, 2014, at the Gate of Heaven Catholic Cemetery in Los Altos, California. /People’s Daily Photo

The same generation as Chang (I am one year older), we had also come of age as journalists in the late 1990s, and similarly lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. Chang spent the final years of her life nearby, in San Jose, and her celebrity was strongly felt in my west coast city, whose press corps often felt marginalized from the bigger publishing centers of New York and Washington, DC.

Now a resident of Berlin, I’ve decided to pick up The Rape of Nanking again. Reading it here, in the seat of the Nazi genocide, is an entirely different experience. Chang’s retelling of the story of the Nanjing-residing German Nazi, John Rabe, whom she dubbed “The Oskar Schindler of China,” has an especially personal significance that was absent two decades ago.

As the world continues to take stock of World War II, and how it informs our world today, books such as The Rape of Nanking are the equivalent of how-to manuals. Not just as literary models, but as calls to action. Without a doubt, there are other Nankings out there that have yet to be discussed. We just need to summon Iris Chang’s courage to make it happen.

(The author is the editor of Souciant.com and the head of publishing at Berlin’s Dialogue of Civilizations Institute. The article reflects the author’s opinion, not necessarily the views of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3