Politics

23:23, 21-Aug-2017

Three reasons why the US refuses to stop military drills with South Korea

By Wang Lei

Barely a week after the Korean Peninsula was pulled back from the brink of war, the United States and South Korea began their bi-annual war games on Monday, ignoring Pyongyang's warning that the exercises would be like "pouring gasoline on fire."

The decision to go ahead with the 11-day Ulchi Freedom Guardian (UFG) exercise has also reflected Washington and Seoul's refusal to accept Beijing's repeated calls for restraint and its "suspension for suspension" proposal, which would see the DPRK suspend its nuclear and missile activities in exchange for the suspension of large-scale military exercises.

As US President Donald Trump and DPRK leader Kim Jong Un just finished trading verbal threats of nuclear war, why has the US refused to halt these joint exercises, risking a revival of tensions? And why has it turned a deaf ear to China's calls?

Here are three possible reasons.

I. It's routine

The US and South Korea have held the Ulchi drills every autumn since 1975, which they say are based on their mutual defense agreement from 1953.

It is one of the two annual military exercises held by the two countries, the other being Foal Eagle/Key Resolve which usually takes place in spring.

This year's Ulchi drills come at a dangerously sensitive time. Following DPRK's two Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) tests in July, the US and the DPRK engaged in a war of words earlier this month, with Trump warning of "fire and fury" and "military solutions," and the DPRK saying that its strategic force was examining a plan for "making an enveloping fire at the areas around Guam."

Although Kim decided last week to hold off on the planned missile strike, he warned that Pyongyang would "make an important decision" if the US continues with its "extremely dangerous and reckless actions on the Korean Peninsula and in its vicinity."

South Korean protesters hold placards saying "stop war exercise" during a rally denouncing the Ulchi Freedom Guardian (UFG) drills, near the US embassy to Seoul, August 21, 2017. /AFP Photo

South Korean protesters hold placards saying "stop war exercise" during a rally denouncing the Ulchi Freedom Guardian (UFG) drills, near the US embassy to Seoul, August 21, 2017. /AFP Photo

Some analysts worry that a large-scale military exercise like this could reignite tensions and revive the possibility of armed conflict, describing it as "needless provocation," according to a CNN report last Tuesday.

But others believe canceling such a regular maneuver would make Trump look weak so soon after his bellicose threats.

Robert Carlin, a retired CIA and State Department analyst of the DPRK, told The New York Times that, "It would take a pretty extraordinary act of leadership" to call off the drills, a move that would draw criticism from "a lot of people."

Despite agreeing with proposals to scale back the exercise, Carlin said many policymakers would see concessions on the annual drills as rewarding DPRK's aggressiveness.

"A huge crowd" would say, if Trump gives in to Kim, the DPRK leader "will take advantage of" the US, Carlin said.

The DPRK tests a Hwasong-14 ICBM, July 29, 2017. /Reuters Photo

The DPRK tests a Hwasong-14 ICBM, July 29, 2017. /Reuters Photo

II. Washington, Seoul say drills are 'purely defensive'

The US and South Korea both say these joint exercises are purely defensive in nature, while the DPRK sees them as a rehearsal for an invasion.

"The Ulchi exercise is a defensive drill conducted annually. We have no intention at all to raise tensions on the Korean Peninsula," South Korean President Moon Jae-in said during a cabinet meeting on Monday, "The Ulchi exercise is aimed at checking on defense readiness aimed at protecting the lives and property of our people."

The DPRK "must understand that it is because of its repeated provocations" that Seoul and Washington "have to conduct defensive exercises," he explained.

Joseph Dunford, chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, said last Thursday that the exercises would be "very important to maintain the ability of the alliance to defend itself," adding that both countries "need to maintain a high state of readiness to respond" as long as the threat from the DPRK exists.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in. /AFP Photo

South Korean President Moon Jae-in. /AFP Photo

Christopher R. Hill, former US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia, said in a recent commentary that the ultimate goal of the DPRK is not just protecting itself but also seeking the reunification of the Korean Peninsula by force.

So it presents a constant military threat to South Korea and the US, he stressed.

On the basis of this judgement, Hill explained that joint exercises are necessary to prevent the US-South Korean military alliance from becoming "weak and hollow."

But not everyone outside the DPRK agrees that the exercises are "defensive."

"The US and South Korea can call the joint exercises defensive and regular as much as they want, but it's not defensive if you're sitting in Pyongyang," John Delury, a professor at Seoul's Yonsei University, told CNN.

On Monday, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying criticized the drills as "not conducive to easing the current tensions" and urged the DPRK, the US and South Korea to address each other's "reasonable security concerns."

III. US unconvinced by 'double suspension' approach

Another reason for Washington's refusal to suspend the drills is that it does not believe the DPRK will give up its nuclear program, even if the exercises are called off.

Many Americans resent Beijing's "double suspension" proposal, rejecting it as establishing a "false equivalence" between DPRK's violations of UN Security Council resolutions and the "defensive" and "legal" joint exercises.

Heather Nauert, spokesperson for the State Department, said last Tuesday that there was "no moral equivalency" between the two.

Pyongyang's "repeated violations of past diplomatic agreements with the US has eroded any appetite for concessions in Washington," Dr. John Nilsson-Wright, an expert on East Asian affairs at the University of Cambridge, wrote on the BBC website recently.

"I think it is a fool's errand to think that our postponing or canceling exercises will cause a positive reaction from the North," David Maxwell, associate director for the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University and a veteran of five tours in South Korea with the US Army, told The New York Times.

According to Maxwell, the US and South Korea agreed to cancel Team Spirit drills in the early 1990s, in exchange for the DPRK allowing international inspections of its nuclear facilities, but the country restarted its nuclear program soon afterward.

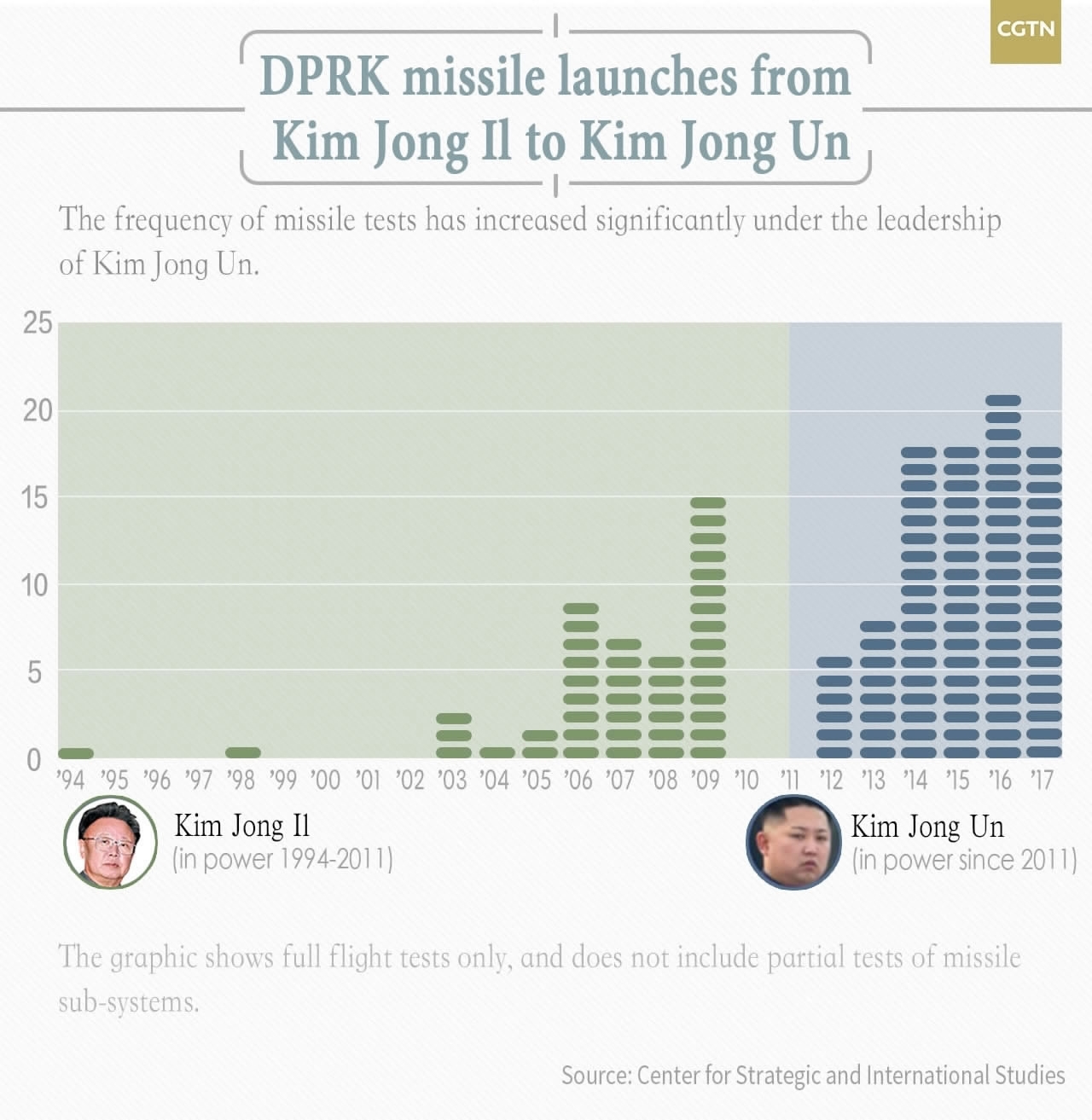

CGTN Graphic

CGTN Graphic

However, as China has repeatedly stressed, the most important thing at the moment is to defuse tensions and stop DPRK's nuclear program, so the "double suspension" proposal, also supported by Russia, is the "most reasonable" and "most realistic" approach under the current circumstances.

"The most urgent thing is to stop DPRK's nuclear and missile program and stop the vicious cycle of escalating tensions on the Peninsula," Hua said at a press conference on Monday, calling on all parties to seriously consider China's "double suspension" proposal.

With deep-rooted distrust between the US and South Korea on one side and the DPRK on the other, as well as disagreements on the cause of and solution to the crisis among the international community, the "vicious cycle" over the DPRK nuclear issue shows no sign of ending soon.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3