Culture

15:51, 19-Sep-2017

China Footprint: Border town bears witness to colonial history

By Tao Yuan

When the British sought to expand the borders of Hong Kong in 1898, the new frontier cut straight through the middle of a small market town called Sha Tau Kok.

The main street of this town, Chung Ying Street, literally translates to China England Street, lies on the border between Hong Kong and Shenzhen. One side of the four-meter street belonged to the Chinese mainland, the other, the former British colony.

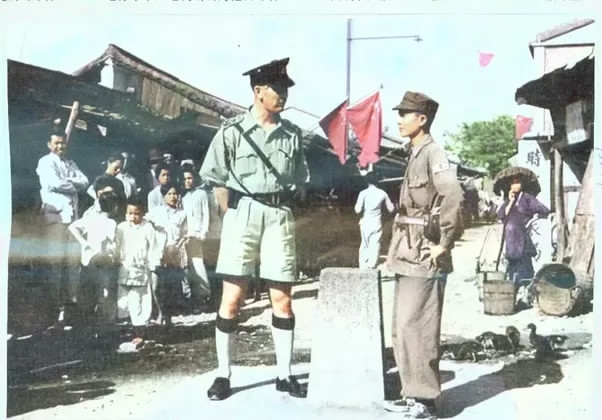

Boundary stone marking the border between Hong Kong and the mainland. /CGTN Photo

Boundary stone marking the border between Hong Kong and the mainland. /CGTN Photo

“It’s a very important demarcation line,” said Sun Xiao, founder and former curator of Chung Ying Street History Museum, comparing the street to the likes of the Berlin Wall and the Armistice Line of the Korean Peninsula. The retired historian came to Sha Tau Kok soon after Hong Kong’s return in 1997, attracted by the heavy historical weight of the small border town. “Chung Ying Street bears witness to a very dark chapter of the Chinese history.”

Shoppers’ heaven

Before China’s opening up, Chung Ying Street was the only part of Hong Kong that Chinese mainlanders could access. In the early 1980s, Sha Tau Kok was flooded by Chinese tourists, who came to buy foreign goods such as soaps, fabrics, and electronic appliances. Shops sprang up on both sides of the narrow street and they did a roaring trade.

“They wanted everything,” says Wu Tianqi, a local village chief. “Customers grabbed everything with passion. Shops sold out all the time.” Professor Lau Chi-pang of Lingnan University estimated the area received nearly 100 thousand tourists a day during that time.

Chung Ying Street boomed as a shoppers’ heaven for mainland tourists. /CGTN Photo

Chung Ying Street boomed as a shoppers’ heaven for mainland tourists. /CGTN Photo

And the mainlanders came for something else – they wanted to see Hong Kong. For many, it was a mysterious world of wonders, richer and better than the mainland. And Chung Ying Street was the only peephole into that world.

“Many first-time visitors would come and ask, is this Hong Kong? Where are the skyscrapers? Where’s Victoria Harbor?” says Bob Ng Ka Hing, a restaurant owner on the mainland side of Sha Tau Kok. “Little did they know they were still far away from the heartland of Hong Kong.”

One country, two systems

Mainlanders now fill the heartland of Hong Kong. At the Luohu immigration control point on Shenzhen’s border with Hong Kong, some 80 million crossings are made every year. About 300 thousand Hong Kong people are working on the mainland, accounting for 8 percent of the total working population of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong returned to China in 1997. Now Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of autonomy under the “one country, two systems” system; the two-way flow of capital, ideas and people has never been freer. Both sides thrive.

Chung Ying Street as a shoppers’ heaven and a peephole into a different world has lost its practical value.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3