Business

17:55, 12-Nov-2017

ECB links China's economy with the euro area

CGTN

China’s size, trade openness and dominant position as a consumer of commodities mean that its transition is crucial for the global outlook, and the spillovers from China’s transition to the euro area economies is estimated at an expansion slowdown of up to 0.3 percentage points, according to a report by the European Central Bank.

Yet China has ample policy space to cushion the economy against a slowdown, thanks to its vast reserves and current account surplus, the ECB noted in the report.

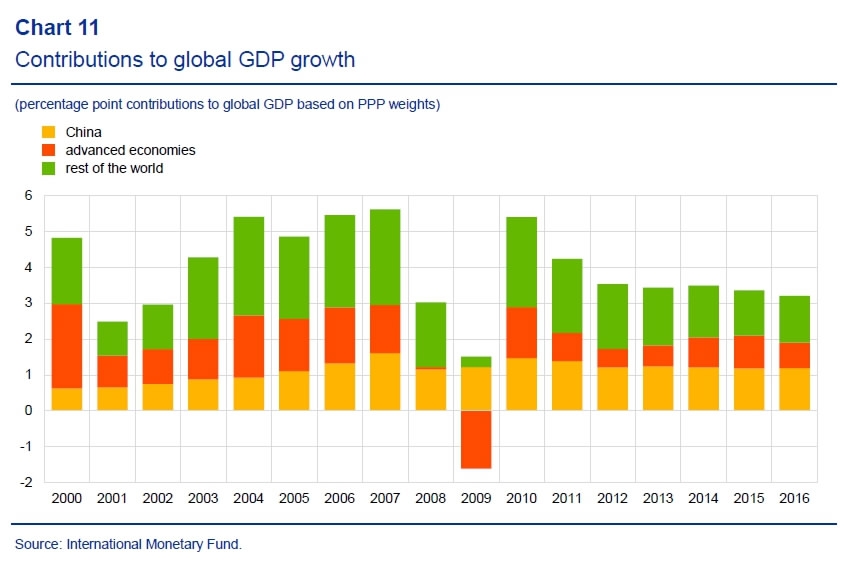

Since 2005, China has contributed an unprecedented one-third of total global growth – more than the combined contribution of advanced economies.

Furthermore, China accounts for around 10 percent of global imports. While that partly reflects China’s important position in global value chains, for many trade partners a significant proportion of value added depends on final demand in China, which means that if something terminal, or merely "bad" happens to China's economy, it would likely lead to a global depression.

Putting China's growth demands in context, the world's most populous nation is one of the world’s largest consumers and producers of many commodities, accounting for over half of global copper, aluminum and iron ore consumption, and a high proportion of global energy consumption.

China’s integration in global financial markets is considerably lower, but the events of the summer of 2015, when equity market and currency volatility prompted a bout of global risk aversion have shown that despite limited direct financial sector exposures, shocks emanating from China can affect global financial markets through the confidence channel.

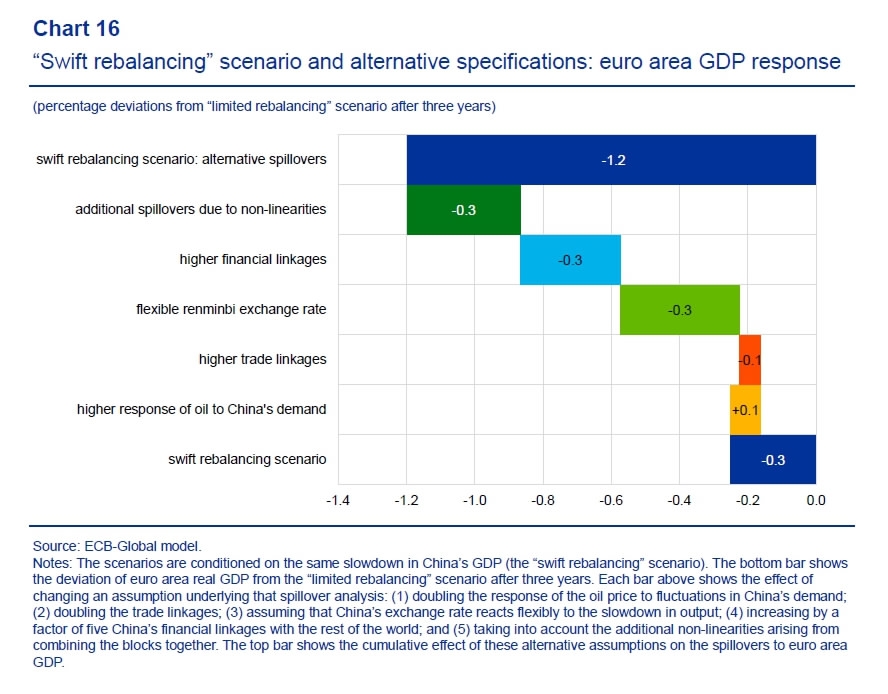

To understand the impact of a transition in China, the ECB used macroeconomic models to study China’s spillovers to the global economy in three possible adjustment paths, and the “swift rebalancing” scenario is more close to China’s reform pledges.

A “swift rebalancing” scenario, which envisages an aggressive reform effort to address existing fragilities and implies an additional slowdown in GDP of cumulatively about 3 percent in China over three years, would slow the currency bloc’s economic expansion by about 0.3 percentage points.

Taking into account larger effects on trade, foreign exchange and global financial markets, the slowdown would amount to 1.2 percentage points.

And while there are risks, especially in the financial sector, China retains policy space to counter a slowdown.

China towards a more balanced growth path

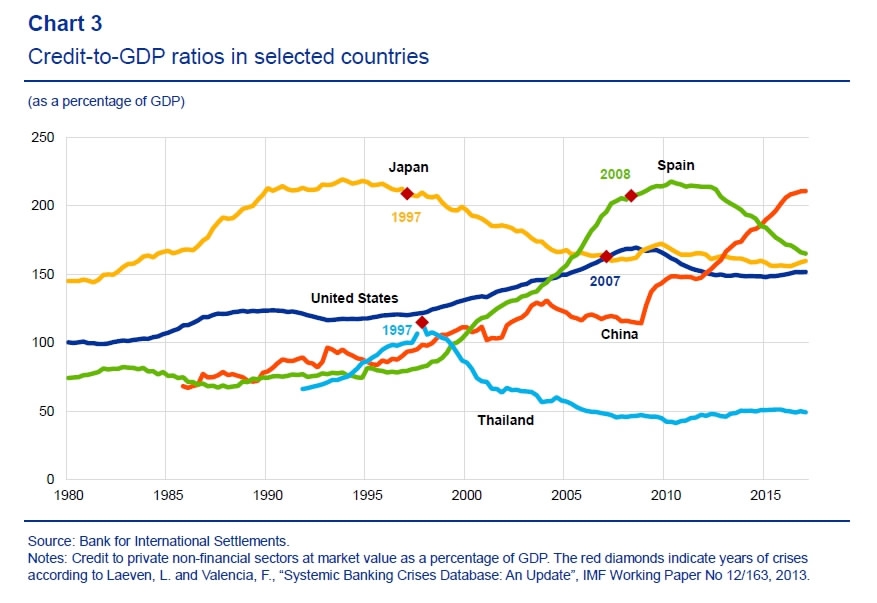

Investment has been particularly strong in China since the late 1980s. High investment rates have also been accompanied by a sharp increase in indebtedness. Both the level and the rate of growth of debt are exceptional for a country at China’s stage of development.

The risks associated with fast-rising indebtedness have been amplified by increased complexity in the financial system.

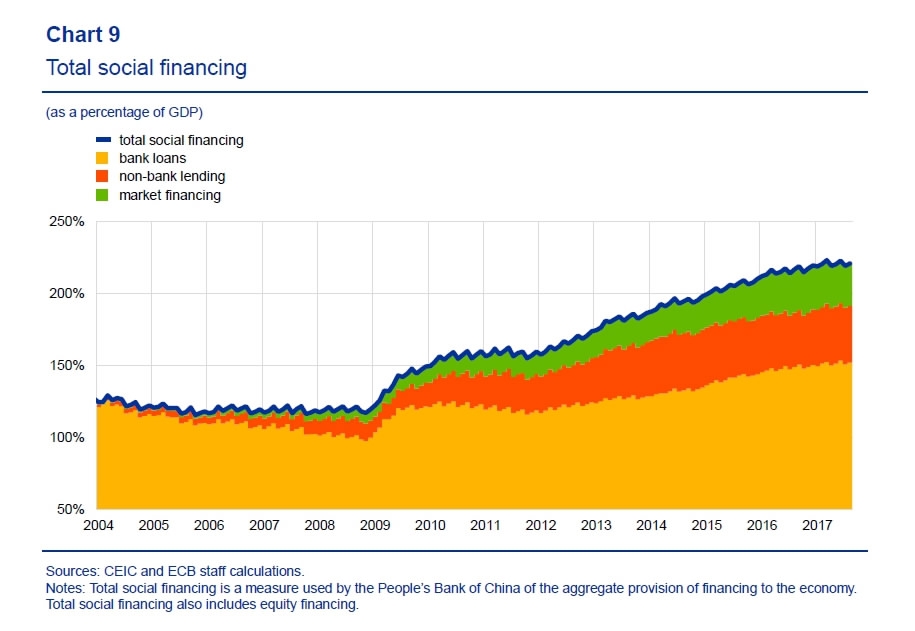

Banks remain the primary source of credit in China and their assets have grown substantially since the global financial crisis. At the same time, non-bank or “shadow banking” activities have also increased, with credit from non-bank sources to the non-financial sector rising to around 70 percent of GDP by 2016.

Although vulnerabilities have grown, China retains policy space to cushion against potential adverse shocks.

China has high national savings, large foreign exchange reserves and a current account surplus, which help to shield it against an external funding crisis.

Moreover, despite slowing growth, the interest rate growth differential remains favorable.

Importantly, the government also retains levers to manage the economy, particularly through its close links with SOEs and banks.

In addition, rebalancing and reform could help to move China onto a more sustainable growth trajectory in the medium term. An adjustment to the structure of production and demand, including less reliance on investment and credit-driven growth, could support the transition towards a more balanced growth path.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3