Opinions

13:03, 04-Mar-2018

Why has the West got China so wrong, so often?

By Zhang Weiwei

- Arguments about China’s collapse have crumbled

- Ideological bias and weak social sciences led to bad predictions

China has developed rapidly over the past 40 years, despite prophecies of doom from overseas observers. Chinese scholar Zhang Weiwei considers why so many predictions about China have proved to be so wrong.

China’s dramatic rise has taken many Western observers by surprise, as China has long been viewed in the West as a combination of a repressive regime clinging to power, and a society full of crises, led by pro-democracy dissidents bordering on rebellion.

This perception has led many China-watchers to predict a pessimistic future for China: the regime would collapse after the Tiananmen event in 1989; China would follow in the footsteps of the Soviet Union in its disintegration; chaos would engulf China after Deng Xiaoping’s death; the prosperity of Hong Kong would fade with its return to China; the explosion of SARS in 2002 would be China’s Chernobyl; China would fall apart after its WTO entry; and chaos would ensue following the US financial crisis 10 years ago. Even by 2017, many in the West still predicted the inevitable hard landing of the Chinese economy with all possible negative consequences for the world.

Yet all these forecasts turned out to be miserably wrong. China did not collapse, but the arguments about China’s collapse have crumbled.

China did not collapse, but the arguments about its demise have crumbled.

- Zhang Weiwei

China is now the world’s largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity. China has produced the world’s largest middle class and China has the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves. Most Chinese own property – China’s home ownership is higher than all Western countries – and China also “exports” more tourists than any other country in the world. China is also the world leader in renewable energy in terms of both investment and output, and it is also a vigorous champion for multilateralism and globalization.

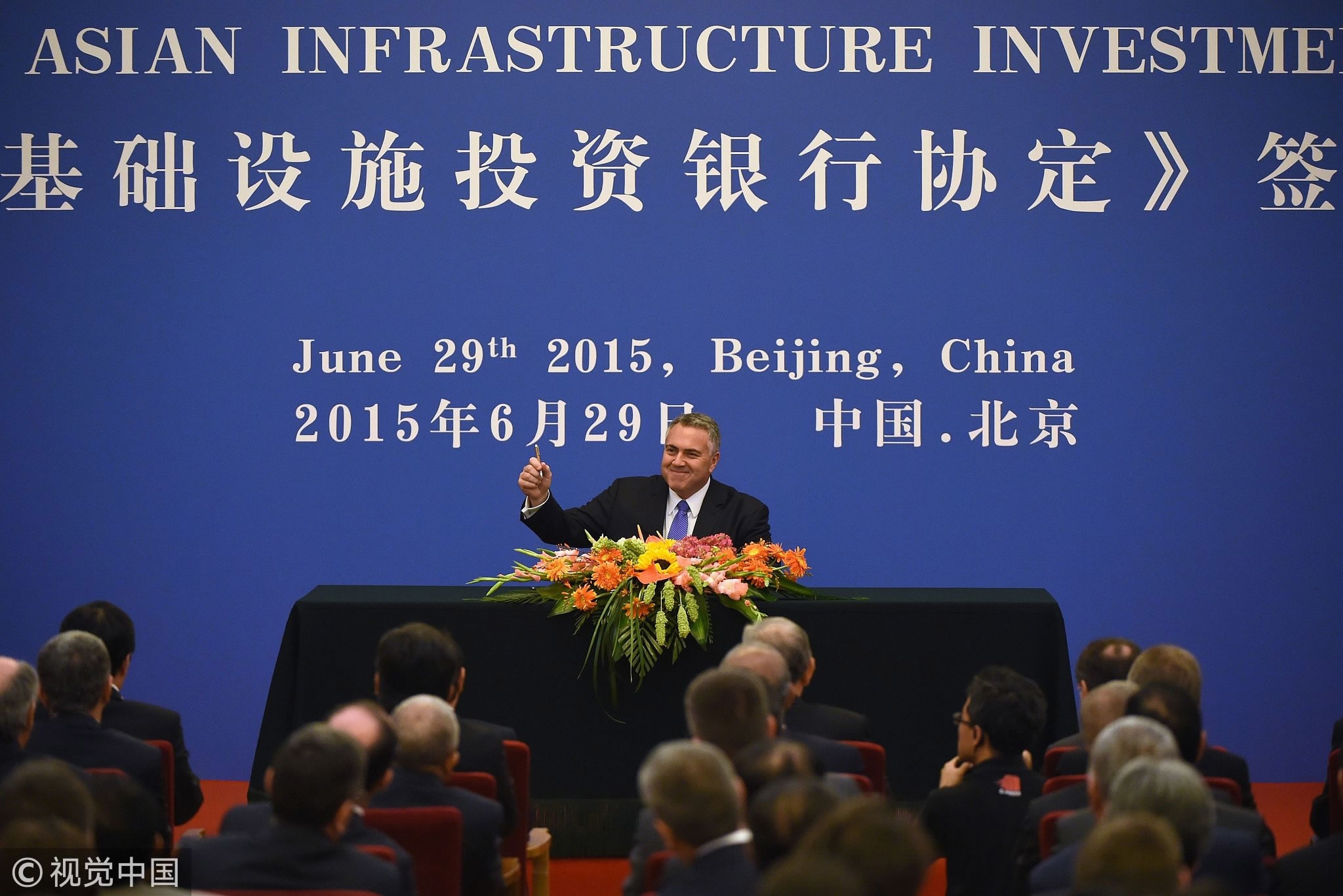

Australia's Treasurer Joe Hockey (C) holds up his pen as he becomes the first to sign the articles of association to set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Beijing, June 29, 2015. /VCG Photo

Australia's Treasurer Joe Hockey (C) holds up his pen as he becomes the first to sign the articles of association to set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Beijing, June 29, 2015. /VCG Photo

Why are so many forecasts wrong about China? There are perhaps three reasons.

First, entrenched ideological bias. Many in the West can’t believe that what they call a communist country, one-party dictatorship, non-Christian nation, could become so successful. My humble advice to these people with ideological bias is to look at China afresh, objectively, or in Deng Xiaoping’s words “to seek truth from facts,” not from ideological dogma.

People with an ideological bias should look at China afresh, or in Deng Xiaoping’s words, ‘seek truth from facts.’

- Zhang Weiwei

Second, the weaknesses of many social sciences developed in the West, especially mainstream political science and neo-liberal economics developed in post-war America, are that they are not only far from real science, but are also out of touch with the real China, and to a great extent, the real world.

No mainstream economists predicted the 2008 financial crisis, the worst since the Great Depression in the 1920s. No mainstream political scientists predicted China’s dramatic rise or the Soviet Union’s breakup. Are the economics and political sciences studied today scientific or simply pseudo-science? This question can be raised today.

Is much of today’s economic or political ‘science’ really scientific, or simply pseudo-science?

- Zhang Weiwei

People lay underneath the iconic Wall Street bull during a rally in the financial district against the proposed government buyout of financial firms, New York, September 25, 2008. /VCG Photo

People lay underneath the iconic Wall Street bull during a rally in the financial district against the proposed government buyout of financial firms, New York, September 25, 2008. /VCG Photo

The assumption that humans are rational beings, the discourse on categories borrowed from the hard sciences, the abstract mathematical models that leave out many variables – all these are inherent weaknesses in these so-called sciences.

If my memory serves me right, Professor John Lewis Gaddis, a leading scholar on Cold War history, once lamented that none of the international relations experts or political science experts predicted the coming breakup of the Soviet Union, joking that even Nancy Reagan’s astrologer could have done better in forecasting this event.

Third, the worst, of course, is the combination of the two mentioned above: ideological bias combined with pseudo-sciences, which is the case for many China watchers or so-called China experts.

Their ideological belief has entrenched their bias, and their pseudo-sciences have made their studies less and less objective, and naturally less and less relevant for China or the real world. Sometimes I have to wonder why I should care about them. Let’s leave them in the darkness.

(Zhang Weiwei is a Chinese professor of international relations at Fudan University and a senior research fellow at the Chunqiu Institute. He is the author of The China Wave: Rise of a Civilizational State. The Chinese Way by Zhang Weiwei is a 10-part CGTN Digital series casting a critical eye over the governance of modern China. Professor Zhang identifies merits and flaws in the Chinese system and contrasts the China model with Western equivalents in a series of short films. )

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3