Health

09:09, 20-Aug-2017

US study alleges cigarette makers promote "smoke without smoking"

Tobacco companies have known for decades that without counseling "nicotine replacement therapy" or NRT, used by consumers to complement smoking, hardly helps smokers quit, according to a study out from researchers at the University of California, San Francisco.

Nicotine patches, gum, lozenges, inhalers or nasal sprays - together known as NRT - came into play in 1984 as a prescription medicine to help people quit smoking. In 1996, at the urging of pharmaceutical companies, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allowed those products to be sold over-the-counter.

Published this week in the American Journal of Public Health (AJPH), the study titled "Tobacco Industry Research on Nicotine Replacement Therapy: 'If Anyone Is Going to Take Away Our Business It Should Be Us'" found that in 1987, three years after FDA first approved nicotine gum as a quitting aid, the tide had turned on the public perception of nicotine; and that by 1992, the tobacco industry had determined that patches and gum by themselves do not help smokers quit.

"It was surprising to discover the industry came to view NRT as just another product," Dorie Apollonio, associate professor of clinical pharmacy and lead author of the study, was quoted as saying in a UCSF news release. "The tobacco companies want people to get nicotine - and they're open-minded about how they get it."

For more than a decade, the companies did not act on this knowledge out of fear of FDA regulation. But once the federal agency started regulating cigarettes in 2009, they went all out in their bid to develop and sell NRT. The Tobacco Papers reveal that companies conjectured that their new nicotine products could successfully compete with pharmaceutical NRT and they set the goal of gaining market control of all products containing nicotine.

The tobacco industry once viewed nicotine patches and gum as a threat to their cigarette sales.

However, with formerly secret internal documents known as the "Tobacco Papers," dated between 1960 and 2010 from the seven major tobacco companies operating in the United States, researchers revealed that cigarette makers had started investing in alternative forms of nicotine delivery as early as the 1950s, but stopped short because people largely regarded nicotine as harmful, and such products might have attracted the attention of FDA regulators.

Smoking is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths every year in the United States, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and another 16 million Americans live with smoking-related diseases.

The costs of such illnesses total more than 300 billion U.S. dollars each year, when including both costs of direct medical care and lost productivity due to secondhand smoke exposure.

Clinical trials show that NRT can help people quit smoking, but only if used in conjunction with counseling and in tapering doses.

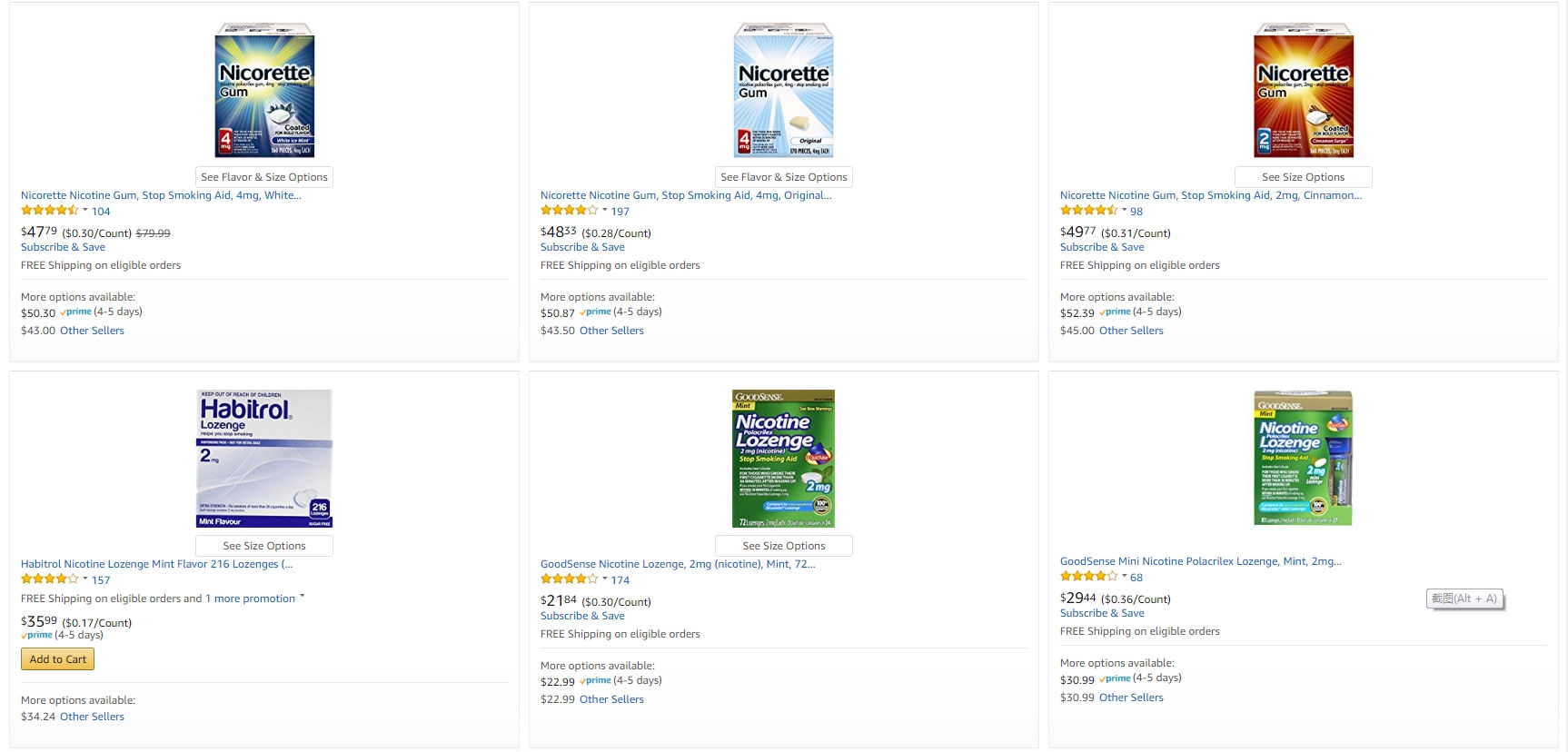

NRT products can be sold over-the-counter and online. / Screenshot via Amazon

NRT products can be sold over-the-counter and online. / Screenshot via Amazon

Over-the-counter availability of NRT made it easy for smokers to get a nicotine fix in non-smoking environments like offices and inside airplanes, with the net result that they were less likely to quit. And given that NRT products are widely available, one of the questions is whether they encourage nicotine abuse.

"Tobacco companies put out these (NRT) products as a way to sidestep policies, by giving people a way to 'smoke without smoking,'" Apollonio noted. "It would be interesting to see in the next 10 years if the companies come up with nicotine water, inhalers, gum, edible products - these are all on their agenda."

Alleging that NRT may normalize lifelong nicotine addiction, the authors urged that the FDA consider regulating the ways in which NRT is being marketed and its over-the-counter availability.

Source(s): Xinhua News Agency

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3