Business

16:35, 14-Sep-2017

How much support does Juncker have for stronger EU economic unity?

Nicholas Moore

Following European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker’s annual “State of the European Union” address on Wednesday, headlines focused on his calls for a “a stronger economic and monetary union” and a “European Minister of Economy and Finance.”

Juncker’s calls for stronger unity and a new minister arguably signal another step towards further economic integration – a bone of contention between member states split by an increasingly wide economic divide.

But does more integration have wide backing from member states, and what would an EU finance minister mean for Europe?

What would an EU finance minister do?

As per Juncker’s speech, the finance minister would act as a coordinator in the event of a financial crisis, promote and support “structural reforms” in member states and “build on the work” of the European Commission’s Structural Reform Support Service.

The Structural Reform Support Service mentioned by Juncker was established in 2015 “to help EU countries to design and effectively implement structural reforms, apply EU law…in a timely manner” and “use EU funds efficiently and effectively.”

Juncker stressed that the role would be created “for efficiency,” and emphasized that he was against “parallel stuctures” like a Eurozone budget or a separate Eurozone parliament, and that this would be a role for all 27 member states.

However, the establishment of a central figure involved in individual member states’ structural reforms and applying EU law would likely prove unpopular with some EU leaders, wary of the union moving towards becoming a federal body.

Who’s in favor?

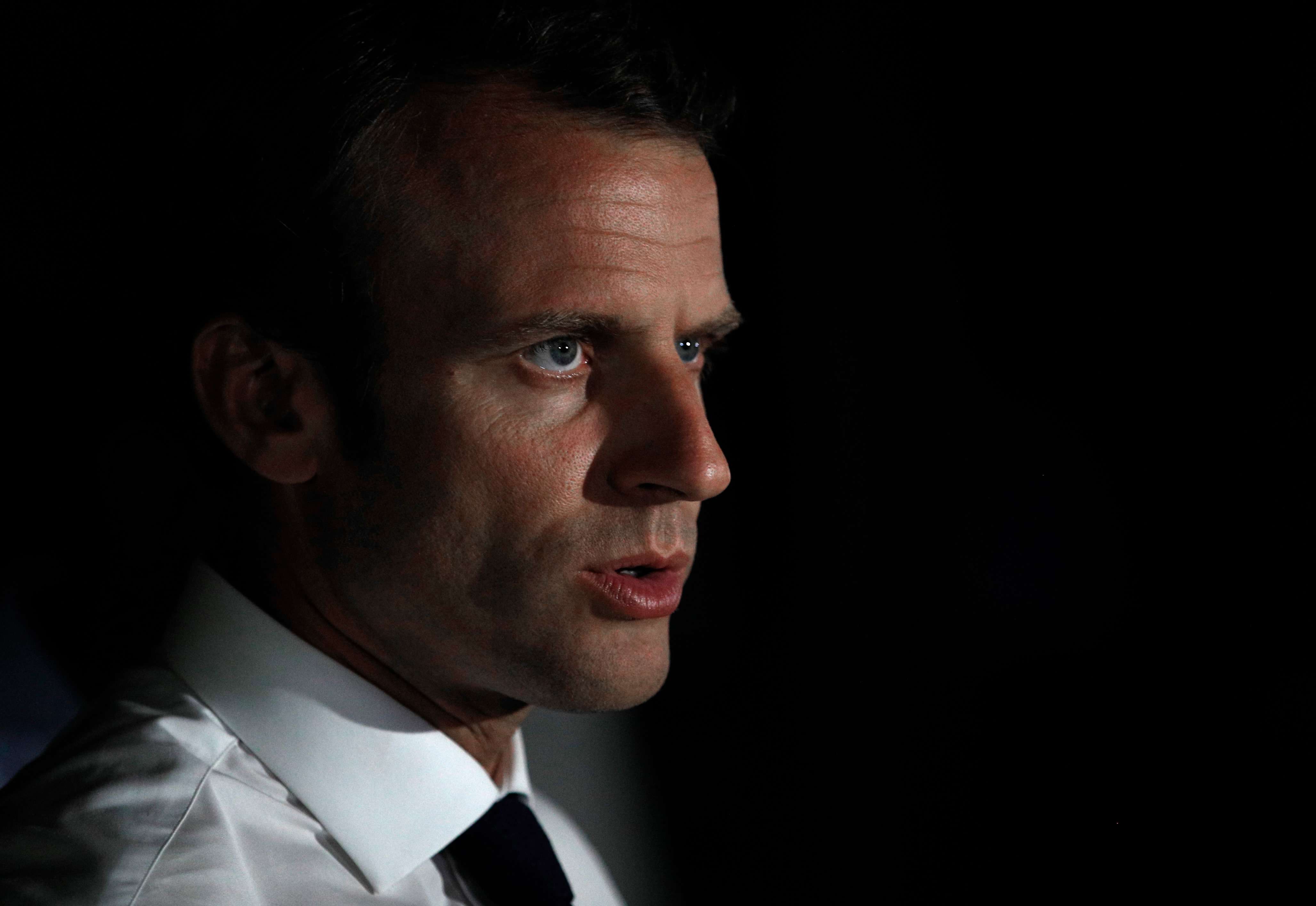

French President Emmanuel Macron, who has pledged to reform the European Union. /AFP Photo

French President Emmanuel Macron, who has pledged to reform the European Union. /AFP Photo

French President Emmanuel Macron has long been a campaigner for economic reform and a strong proponent of having an EU finance minister. Macron’s En Marche! movement’s manifesto included calls for a finance minister responsible just for the Eurozone, as well as the Eurozone budget and parliament. Speaking in Athens earlier this month, Macron called on EU member states to advance economic reforms with “maximum ambition.”

Macron and Merkel are expected to unite and forge ahead with plans for greater economic integration within the EU. /AFP Photo

Macron and Merkel are expected to unite and forge ahead with plans for greater economic integration within the EU. /AFP Photo

In Germany, Macron has an ally in Chancellor Angela Merkel with regards to more integration and creating a finance minister role, saying in June that both should be “strongly considered.” Like Macron, Merkel is in favor of greater European integration and alignment of economic policy, and if she is re-elected as Chancellor on September 24, the pair are expected to form a united front in favor of greater European integration.

Elsewhere in Europe, Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy in August said his country backs “a European finance minister and a European budget which will progressively bring closer together living standards and the wealth of all European countries.”

Who opposes further integration?

The European debt crisis has revealed a divided union, with calls for greater integration meeting resistance from countries like Hungary, which has already resisted central EU policy over refugee quotas during the migrant crisis.

In an interview with Reuters on September 12, Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto said, “I definitely do not share the approach ... that (the) less sovereignty on the level of the member states, the stronger the EU will be. When asked for Hungary’s stance on an EU finance minister, Szijjarto replied, “Since we are not members of the eurozone, this question will be decided without asking our opinion.”

Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto. /AFP Photo

Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto. /AFP Photo

Other Eurosceptic governments like Poland would likely be wary of having an EU finance minister, with Macron’s tough rhetoric on reforming EU labor laws on posted workers winning him no friends in Eastern Europe. Polish Prime Minister Beata Szydlo called Macron “arrogant” in August and lacking in “political experience.”

Juncker’s speech was also viewed with suspicion by the Republic of Ireland on Wednesday, with the Irish government saying it would not support, “Any change to existing EU voting rights on corporation tax,” and calling for “further careful consideration and analysis” of Juncker’s proposals “to avoid any potential unintended effects.”

Ireland is one of several EU states with low business tax policies which favor large corporations, and with the Republic’s GDP expected to grow by four percent in 2017 and 2018, threats to do away with veto rights for individual states on matters like tax law will be far from popular in Dublin.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3