China

16:15, 22-Nov-2017

Tackling poverty with taro in China

By Sim Sim Wissgott and Zhu Danni

Taro, bees and tourism – unlikely bedfellows, they however have one thing in common: they are all part of China's battle against poverty.

Fujian Province in the southeast has the 11th highest gross regional product in China. But this does not mean the battle is over, with poverty alleviation measures still being tried in various areas as the central government seeks to achieve a "moderately prosperous society in all respects" by 2020.

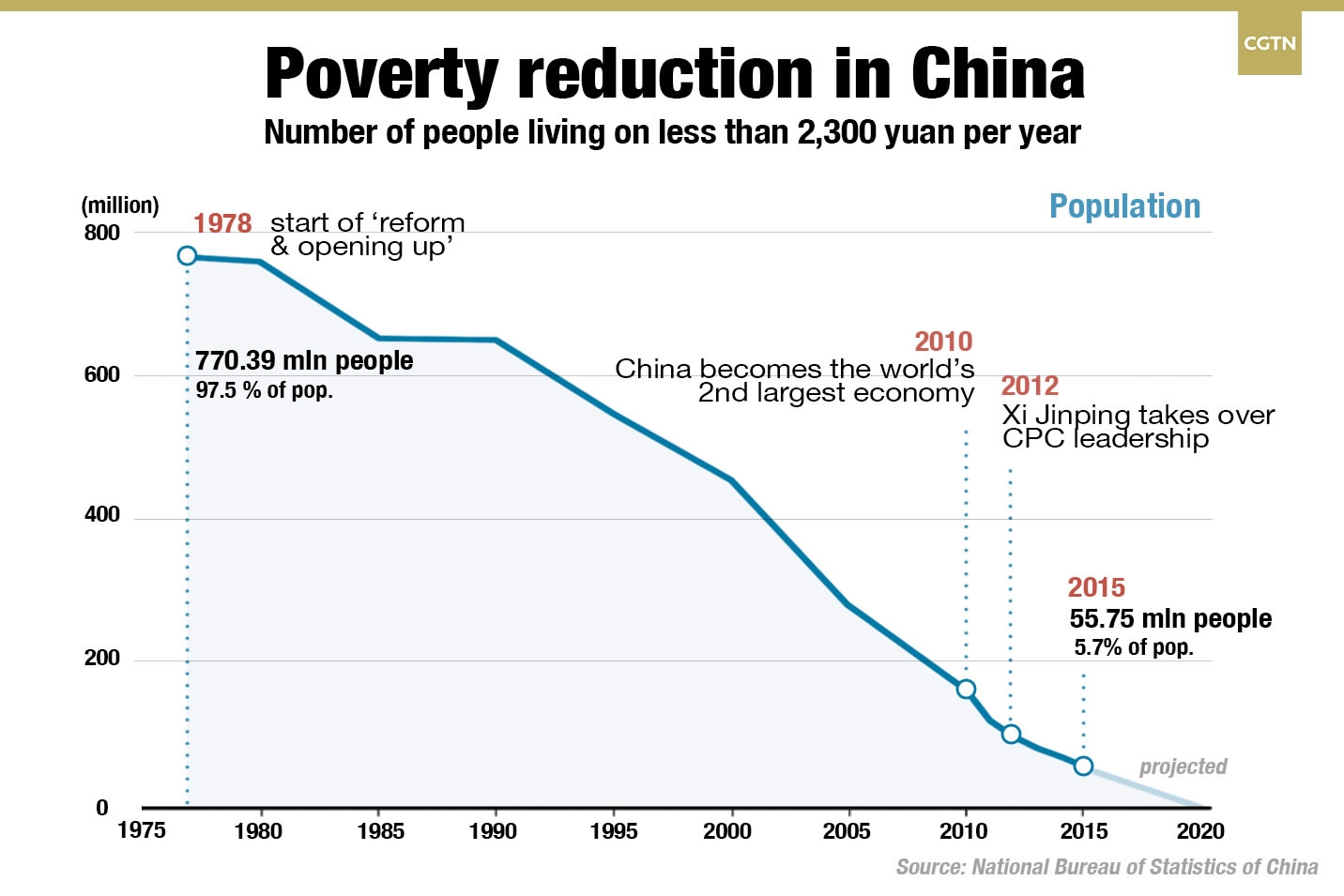

By then, China wants to have completely eradicated extreme poverty. That means pulling a remaining 40 million people – equivalent to half the population of Germany – out of poverty over the next three years. That’s an annual 10 million people who currently live on 2,300 yuan per year – 346 US dollars or less than one dollar per day.

CGTN visited several villages in Fujian to find out more about China's efforts in fighting poverty.

Going to the root of the problem

With poverty disproportionately affecting the countryside, rural development has played a key part in the government's anti-poverty efforts.

Taro grown in Toucheng Village, Fujian Province. /Fuding City Publicity Department Photo

Taro grown in Toucheng Village, Fujian Province. /Fuding City Publicity Department Photo

In Toucheng Village, in the northeast of Fujian Province, taro farmers have turned to organic production. A Beijing company supplies them with free fertilizer and new farming techniques, and buys all their taro at above-market prices – meaning the farmers need to invest less money up front and have more income security in the end. This pilot project, involving about 70 farmers, was just launched in the spring but if successful will be expanded to other villages in Fuding County.

Already, this year’s taro harvest was up 20 percent.

“The soil is better, the quality of the vegetable is better and it tastes better,” one of the farmers told CGTN.

“For each jin (0.5 kilograms), they are paid two yuan (0.30 US dollar) more than the market price,” added Wang Zongxu, deputy secretary of the local CPC committee. “One mu (0.07 hectares) on average is 2,000 jin… so per mu they will get 4,000 yuan more.”

Bees and tea

Another village CGTN visited has started beekeeping and producing honey to supplement locals’ income, while elsewhere investment has been poured into plantations of white tea – a Fujian specialty.

CGTN Graphic

CGTN Graphic

Beijinger Li Xiaojun, whose company recently acquired 10,500 mu (700 hectares) of white tea fields, noted that the process had been made easy for them. “The local government, local tourist offices and tea companies have all been very supportive,” he said.

Ziplining and rafting

Farther south, Chixi, labeled No. 1 Poverty Alleviation Village, has turned to tourism as a way to boost its economy. A youth camp set up by the river ensures regular visits from schools looking to organize outdoor activities for their students. Nestled in a green valley surrounded by low peaks, Chixi also attracts visitors from the city eager to escape to nature for a day.

“The scenery is beautiful and they have a good youth camp,” said Wang Ensheng, who brings middle school students from nearby Xiapu to the area twice a month. “The students are happy with the trip because they can be close to nature, get fresh air and get away from the city.”

Villagers in Chixi making tofu. /CGTN Photo

Villagers in Chixi making tofu. /CGTN Photo

“There was good advertising for this place and the fact that this is a poverty alleviation village. That’s why we came to visit,” another woman from Xiapu on a day trip with her girlfriends told CGTN. They planned to go water rafting and ziplining and would “definitely” recommend this place to friends for its beautiful scenery and nature, she said.

Under severe debt until a few years ago, Chixi is now making a profit, with 45 percent of that coming from tourism and 30 percent from white tea, according to the village's Party secretary Du Jiazhu.

Average income in the village of 1,800 is now 15,000 yuan per year, he said.

Centenary goal

As the Communist Party of China (CPC) prepares to celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2021, poverty alleviation remains at the core of its “centenary goal” of achieving a “moderately prosperous society”.

White tea plantation in Fujian Province, China. /CGTN Photo

White tea plantation in Fujian Province, China. /CGTN Photo

Besides rural improvement, anti-poverty measures have included: job training; subsidies to help local entrepreneurs set up businesses; incentives to attract young people back to the countryside; and an improved public healthcare and social security system, as many of those living in extreme poverty do so because of illness and an inability to pay mounting medical bills.

Access to education for all children has also been a priority, as has improving infrastructure in remote regions, relocating people away from disaster-prone areas, and pairing wealthy and poor provinces – such as Fujian and western Ningxia – to support development.

Historic efforts

In 1978, China had over 770 million people living in extreme poverty. Its efforts since then have seen “the fastest rate of poverty reduction ever recorded in human history,” Bert Hofman, World Bank director for China, Mongolia and Korea, noted earlier this year.

Poverty alleviation offices have been set up at all levels of the government and top officials have described it as a “battleground.”

Beekeeping in Banyueli Village, Fujian Province. /CGTN Photo

Beekeeping in Banyueli Village, Fujian Province. /CGTN Photo

Last year, the central and local governments reportedly spent a record 100 billion yuan (15 billion US dollars) in efforts to fight poverty.

President Xi Jinping – who spent 17 years in Fujian, including as governor, and is credited with introducing poverty eradication schemes already during his tenure there – again highlighted the issue last month at the 19th CPC National Congress.

Praising the “decisive progress” made over the last five years, he nevertheless warned that “poverty alleviation remains a formidable task.”

Some 800 counties and 128,000 villages are still deemed extremely poor, according to official figures.

Top officials also acknowledge that the last few million will be the hardest ones to help. With able-bodied workers already helped through job schemes, relocation and subsidies, those still suffering extreme poverty are likely to be the handicapped and elderly, especially in remote regions.

"The task has become more difficult and costly as the process approaches its end," Liu Yongfu, head of the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development, reported in August.

1444km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3