Business

16:43, 30-Mar-2018

Graphics: Why US trade protectionism belongs in the past

Nicholas Moore

US President Donald Trump’s proposed heavy tariffs on Chinese imports have sparked widespread concerns over a trade war, and what that would mean for the global economy.

Whatever happens, Trump was elected on the mandate that he would “make America great again,” promising to put America first and to tackle the country’s 350 billion US dollar trade deficit with China.

Why has the US faced such a backlash over its stance on trade and the economy?

The current administration’s train of thought and interpretation of data belongs to a different era. Its policies fail to take into account the changing world that the US helped create, and ignore the fact that the US is already, in many different ways, a strong and “great” economy.

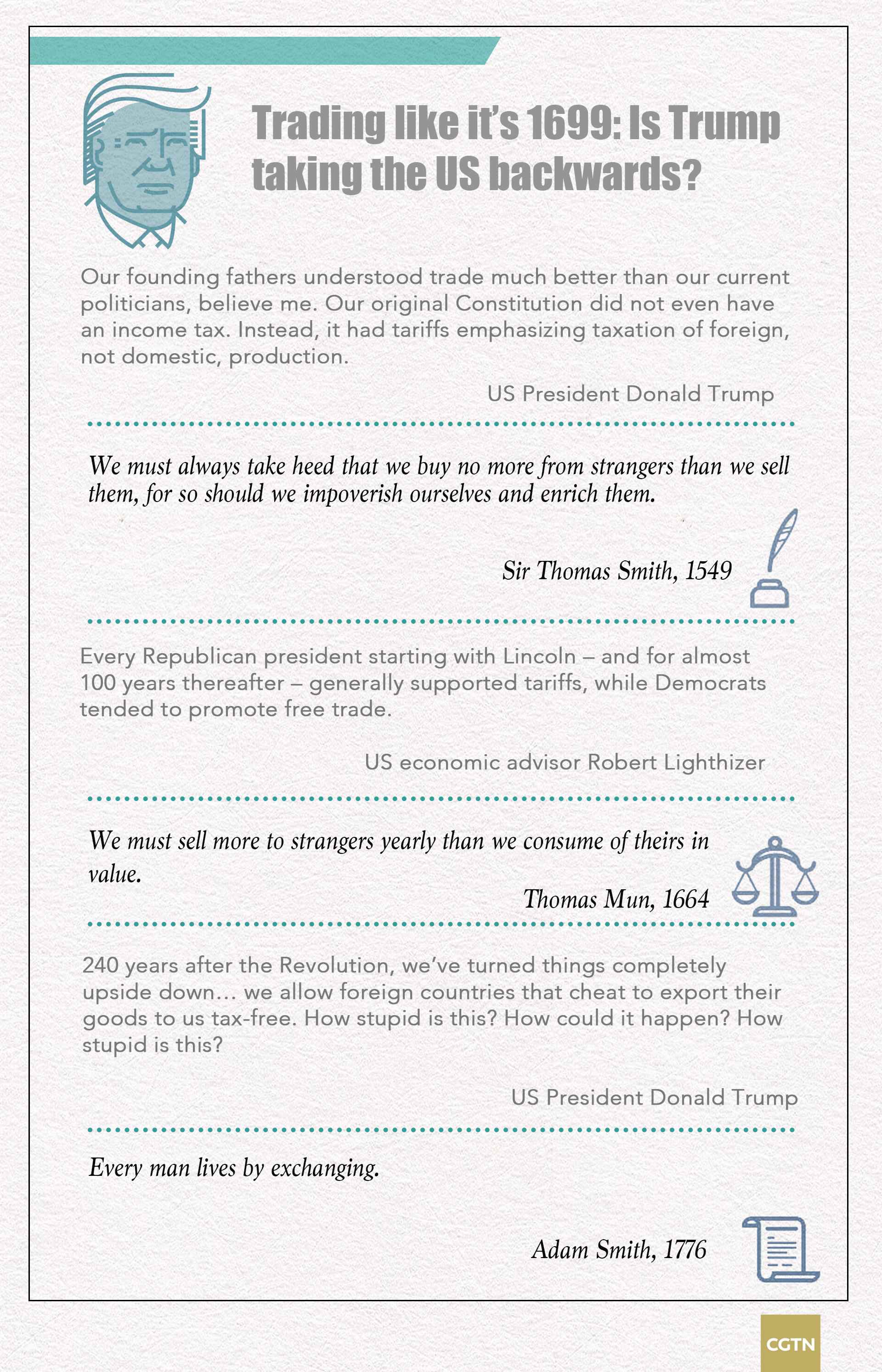

Trump’s obsession with the trade deficit harks back to protectionism and mercantilism, an ideal that died out centuries ago, when European colonial empires looked after their own interests in an era of competition and exploitation.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

Trump has spoken favorably and without irony about how the US founding fathers implemented a tariffs-based system rather than taxation, but he forgets that the US war of independence against British colonial rule began with a struggle against protectionism, in the form of the Boston Tea Party.

While it may be a stretch to say Trump wants to take the US backwards by a couple of centuries, protectionism belongs in the past. Even renowned economist Adam Smith consigned mercantilism to the past, and that was more than 200 years ago.

Since then the world has changed beyond recognition, and many of those changes are thanks to the US taking the lead in advancing globalization and free trade throughout the 20th century.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

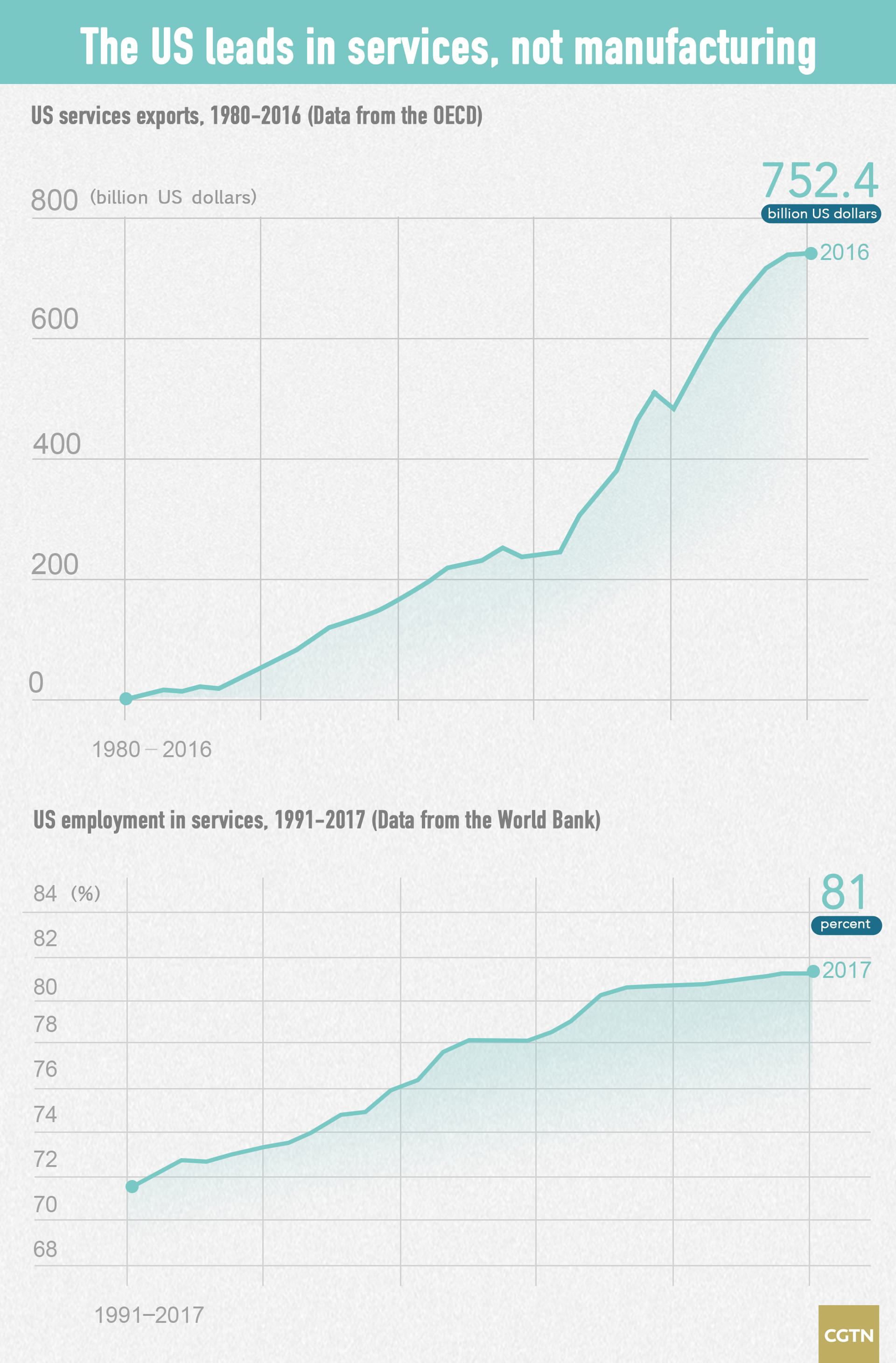

Going into the 21st century, the US economy – like other developed economies – is undergoing a dramatic shift, thanks to continued globalization.

The US is no longer an economy that relies heavily on manufacturing and production of goods – 81 percent of the workforce is employed in the services sector, according to the World Bank. No other country exports as much in services as the US.

It’s up to Trump to decide whether or not the US is a modern services-based economy, or still a 20th century manufacturing-led exporter of goods. The US leads a significant services surplus with many countries – including China, while the American services sector has shown strong growth for almost 100 consecutive months.

With China looking to transition from a manufacturing-led economy to a services-led model, the US is in an enviable position.

Many Trump supporters will point to the country’s huge trade surplus when manufactured goods are included, but the transition that the US has undergone has allowed it to move funding away from production lines and into world-beating innovation.

Forward thinking China has not only promoted free-trade and globalization, but it has also recognized that the future of manufacturing will revolve around automation – an area in which the US could have taken a commanding lead if there was less political focus on the trade deficit.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

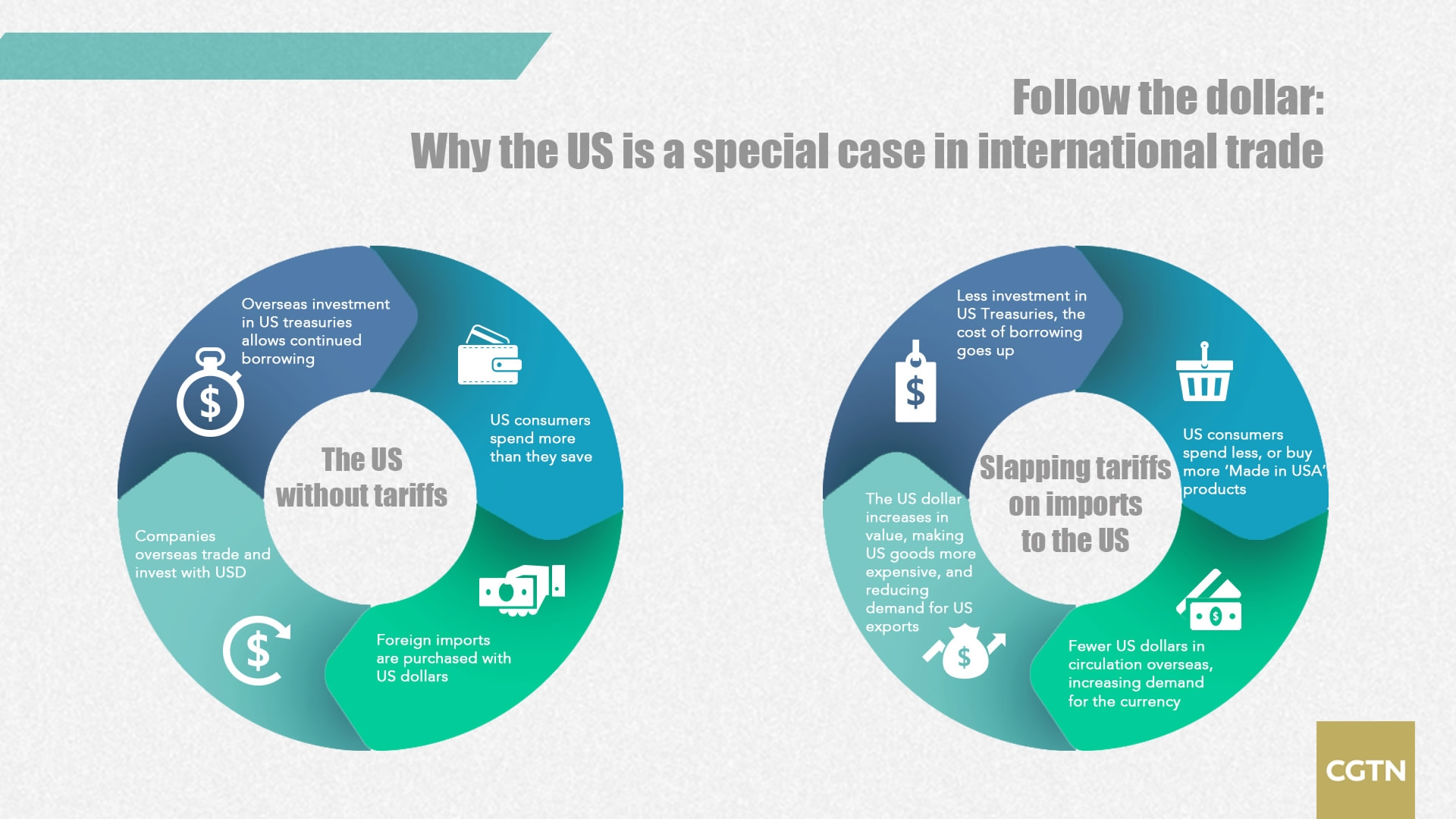

Do trade deficits even matter? As with all areas of economics, it depends on who you ask. Other developed countries run significant trade deficits, while every significant dip in the US deficit since 1980 has coincided with a recession.

But there is no argument against the fact that the US is a very special case, thanks to the role of the US dollar as the global reserve currency.

The investor safe-haven of US Treasuries means that, for the foreseeable future, there will always be strong international demand for US dollars. Tariffs and trade barriers would likely be a short-term boost for “Made in America” products, reducing demand for foreign goods and lowering the amount of US currency in international markets.

In the long-term, that would push the price of the dollar up, reducing foreign demand for “Made in America.” With the US under Trump looking to export more goods and services than it imports, tariffs and trade barriers would do very little to address the trade deficit.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3