Tech & Sci

12:05, 09-Oct-2017

New test identifies antibiotic-resistant bacteria in 30 minutes

Scientists have pioneered a method to detect antibiotic susceptibility for urinary tract infections in less than 30 minutes, potentially enabling patients to be diagnosed and prescribed effective treatments during a single clinical visit.

The new test developed at California Institute of Technology that identifies antibiotic-resistant bacteria could shorten wait times from three days to less than 30 minutes and could help reduce the spread of superbug bacteria, according to the study published Wednesday in the Science Translational Medicine.

The discovery of antibiotics in the early part of the 20th century changed modern medicine. Simple infections that previously killed people became easy to treat. But because of overuse and misuse, antibiotics are losing their effectiveness.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria /VCG Photo

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria /VCG Photo

Many species of bacteria have evolved resistance to commonly used antibiotics and multidrug-resistant bacteria, or so-called superbugs, have emerged, plaguing hospitals and nursing homes. Last month, the World Health Organization issued a dire warning: The world is running out of antibiotics.

"Right now, we're overprescribing, so we're seeing resistance much sooner than we have to for a lot of the antibiotics that we would otherwise want to preserve for more serious situations," Nathan Schoepp, co-author of the study, said in a statement.

According to the Caltech team, when treating bacterial infections, doctors tend to ignore first-line antibiotics like methicillin or amoxicillin, drugs that bacteria are more likely to be resistant, and skip straight to the stronger stuff, like ciprofloxacin.

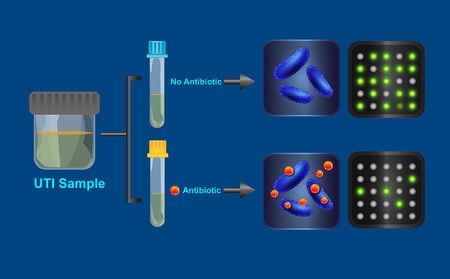

DNA markers show up as fluorescing dots in the test, making them easy to count. Here, the test shows a bacterial sample grew more poorly in an antibiotic solution, indicating that the bacteria do not have resistance to that antibiotic. /Caltech Photo

DNA markers show up as fluorescing dots in the test, making them easy to count. Here, the test shows a bacterial sample grew more poorly in an antibiotic solution, indicating that the bacteria do not have resistance to that antibiotic. /Caltech Photo

They do so because there's a high chance that the weaker drugs won't work, but it is not ideal. That's because the increased use of second-line antibiotics makes it more likely that bacteria will also become resistant to these stronger drugs. Worryingly, scientists are warning that our last line of defense is beginning to fail.

However, there has not been a quick and easy way for a doctor to know if their patient's infection is resistant to particular antibiotics. Normally, to find out, the doctor would have to send a sample to a testing lab and wait two to three days for the results.

Rather than simply assuming that first-line antibiotics wouldn't work, the Caltech team's test was designed to allow them to quickly identify what bacteria is causing a particular infection, and prescribe a drug accordingly.

They focused on one of the most common types of infections in humans, urinary tract infections (UTIs), which lead to almost eight million primary care visits every year (and almost always require antibiotics). However, the emergence of bacterial resistance remains a growing threat to global health, rendering many antibiotics ineffective, researchers say.

A visualization of how the antibiotic resistance test works. /Caltech Photo

A visualization of how the antibiotic resistance test works. /Caltech Photo

Using 54 urine samples from patients with the bacteria Escherichia coli-caused UTIs, the researchers compared the results of their test to a standard test that normally takes two days. Their new method was found to be 95 percent match to the results of the existing test.

"Therapies are driven by guidelines developed by organizations like the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention without knowing what the patient actually has, because the tests are so slow," says Rustem Ismagilov, Caltech's Ethel Wilson Bowles and Robert Bowles Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering and director of the Jacobs Institute for Molecular Engineering for Medicine.

"We can change the world with a rapid test like this. We can change the way antibiotics are prescribed."

Researchers plan to begin running the test on other types of infectious bacteria to see how well it performs. They also hope to tweak the testing procedures to work with blood samples.

10072km

Source(s): Xinhua News Agency

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3