China

22:46, 08-Mar-2018

I HAVE A QUESTION: How will China's family planning policies change?

By Han Bin, Wei Lynn Tang, Zhuang Yuying

WILL CHINA ABANDON FAMILY PLANNING POLICIES?

There’s a saying: It is one’s decisions that determine one’s fate.

There’s also the law of unintended consequences. An aging society is not what China had in mind when it first implemented its “One-Child Policy” almost four decades ago.

Thus, China has taken a step towards "loosening" its family planning policies by allowing couples to have a second child since January 2016.

He Ningyuan, a bar owner, and his wife, were among the couples who took advantage of this policy "lift," believing there is a need to have a second child.

“There’s only so much [time] that a parent can accompany a child. When the child grows up and goes to university, he or she may be lonely – even when they have friends. Because I have an older brother, I can understand this sentiment,” Ningyuan says.

“Yes, being an only child will make him or her more independent, but the child can also be more selfish – especially caring about their own independence and happiness.”

Ningyuan is financially comfortable and, as such, costs in bringing up an additional child may not pose as much of a pressure to him as to many others. However, that doesn’t mean things are as easy. “My wife and I have less freedom [to do our own things] now. We also feel tired emotionally. But overall, we are happy.”

China saw 17.9 million and 17.2 million newborns in 2016 and 2017 respectively, falling below authorities’ projection of 20 million a year. On the flipside, people aged 65 and above increased eight million in 2017 to 158 million, accounting for 11.4 percent of the country’s population.

While He Ningyuan hasn’t felt the pinch in additional costs of bringing up a second child, he says is aware of the huge amount of extracurricular activities his children will have to take on as they grow up. /CGTN Photo by Wang Jigang

While He Ningyuan hasn’t felt the pinch in additional costs of bringing up a second child, he says is aware of the huge amount of extracurricular activities his children will have to take on as they grow up. /CGTN Photo by Wang Jigang

MOBILITY IN SOCIETY CHANGES THINGS

Yu Jinyao, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, reasons: “When you lift a policy, the impact will only be felt years later.”

As it is, Chinese women’s fertility rate has yet to rise sharply despite the implementation of the two-child policy, he says.

“When my parents were fertile, the country took control of the birth rate; but when my parents get old, who will take care of my parents?” Yu asks.

Granted, it takes time to unwind the effects from a major policy. However, Yu, who is also a CPPCC member, says the foundation for taking care of the elderly is no longer there.

“It’s traditional for raising children to provide against old age. But even with a second and third child now, they may not be able to look after you, because the society is so mobile,” Yu says, citing the different locations in which parents and their children live in today.

“The one-child policy’s focus on controlling population has been met. Now the government should focus on its population’s quality and structure,” he adds.

As people live longer, the upcoming group of elderly will also have their parents and another generation of elderly above them in time, and hence, the country’s aging society is grave, Yu explains.

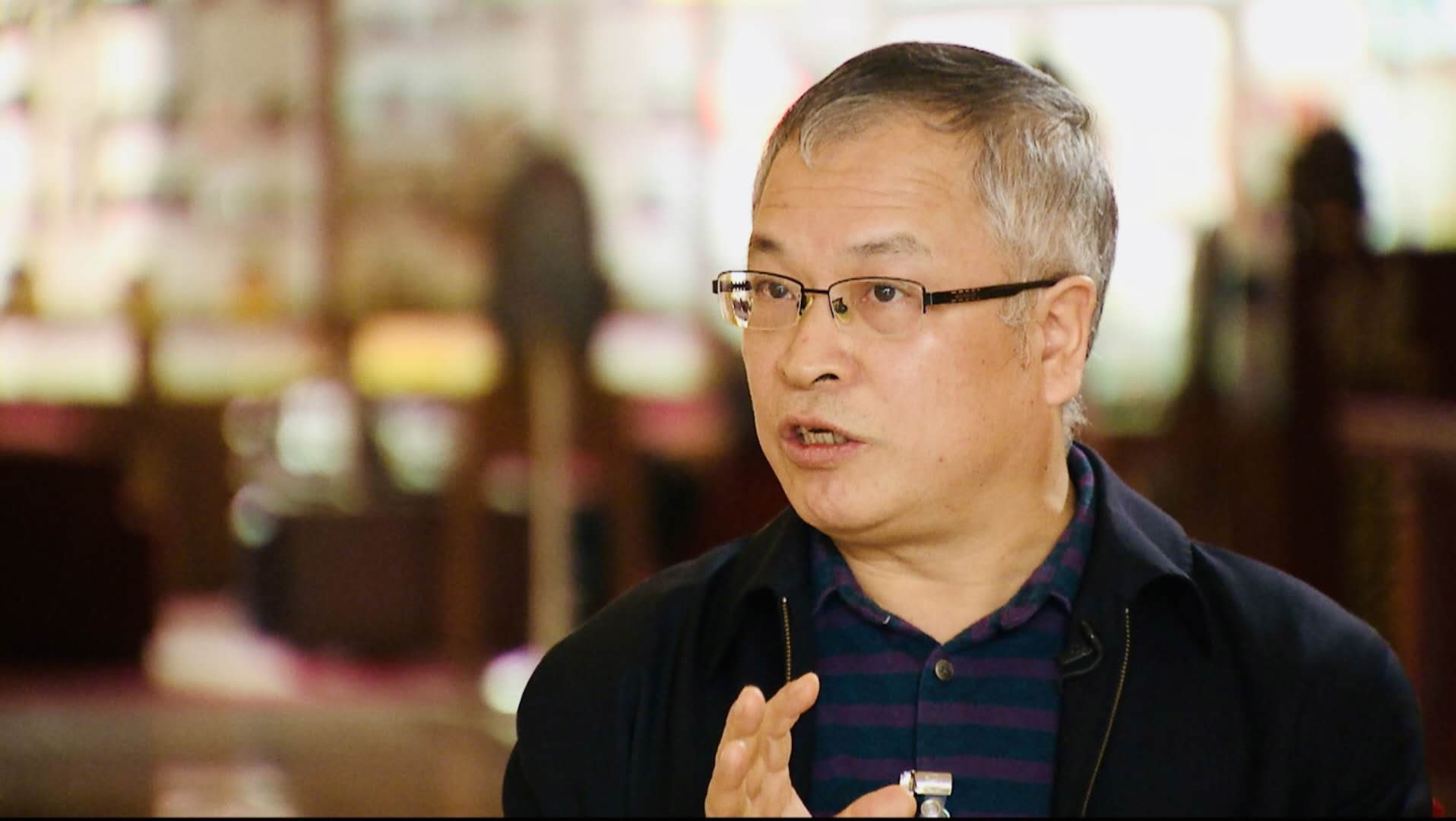

Yu Jinyao is still analyzing as to why the two-child policy has yet to pave way to more newborns. /CGTN photo by Wang Jigang

Yu Jinyao is still analyzing as to why the two-child policy has yet to pave way to more newborns. /CGTN photo by Wang Jigang

GOVERNMENT POLICIES

Citing the imbalance that the one-child policy has brought to Chinese society, Yu says ultimately it is necessary for the government to step in with policies such as taxes and subsidies.

Firstly, Yu calls for country-wide subsidies to look after the elderly with only one child. In his words, “as our one-child policy was nationwide, so should the elderly’s when it comes to taking care of them, such as pension benefits.”

“Local governments can subsidize the elderly based on their financial situation. But the treatment should be the same for both the rural areas and the city within the same province,” Yu suggests.

He also calls for the country to support and promote ways that some of the local governments are already adopting, when it comes to nursing leaves and professional medical services for the elderly.

Zhang Qiong, a mother of two, says longer maternity leaves for mothers who are working, as well as more schools and lower education fees, would be nice.

As for He Ningyuan, he calls for loosening property ownership rules in Beijing, and for loan requirements to be less stringent.

“Those with no household registration in Beijing can only own one property. If the government can allow us to have two properties, when I get old I can have my own house, and my children, their own.”

Experts have linked China’s vast economic growth in the past four decades to its booming population “dividend”. While the dynamics now may be different, all eyes will still continue to be on China’s birthrate numbers in the future – for it still has the largest population and is the second largest economy in the world.

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3