Opinions

13:14, 25-Nov-2017

Opinion: What now for Zimbabwe after Mugabe

Guest commentary by Atia Azohnwi

As Robert Mugabe’s close to four-decade grip on Zimbabwe fades away, many are in doubt about what will change. He is seen as the father of modern-day Zimbabwe, the man who freed his country from white minority rule.

A democratic process gave Mugabe legitimacy as he became prime minister and stood for decades as a prominent icon of African self-determination, which overshadowed his vision for his homeland.

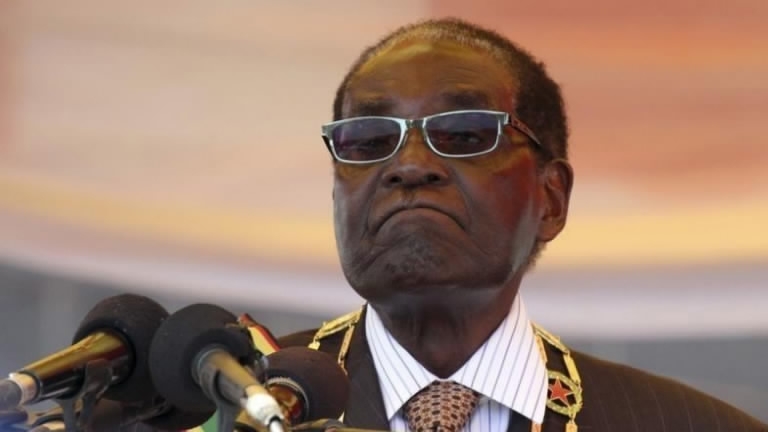

Zimbabwe's former president Robert Mugabe /Reuters Photo

Zimbabwe's former president Robert Mugabe /Reuters Photo

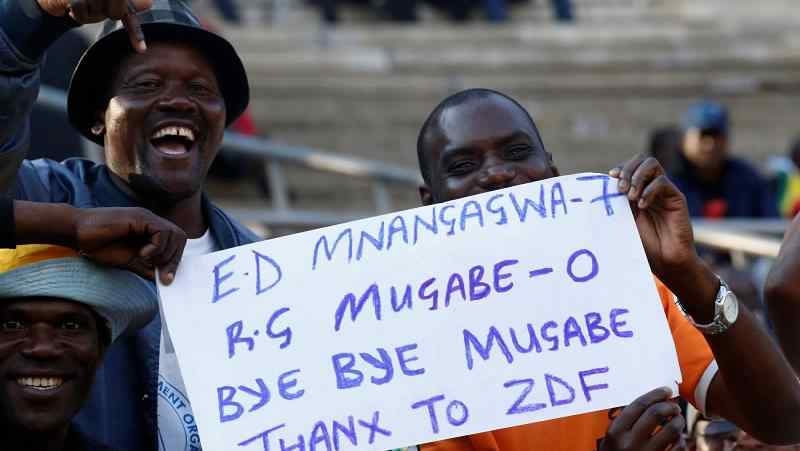

Endowed with natural resources and human capital, Zimbabwe, once Africa’s breadbasket, is believed to have been ruined by Mugabe’s half-baked economic agenda and his step-by-step stifling of the opposition. Mugabe's resignation after 37 years in power has given way to many analyses from across the globe. While some see it as a bloodless revolution, many are those who see it as a bloodless coup.

Some Francophone pseudo-intellectuals who arrogate to themselves the title of hardcore pan-Africanists have pledged unwavering support for dictatorship in Africa in the name of African self-determination. They thus see the situation in Zimbabwe as treachery.

The British may be celebrating the fall of Zimbabwe’s long-time strongman. The economy was apparently being sabotaged by the West because Mugabe would not bend. The war on land obviously landed Mugabe in the British black books.

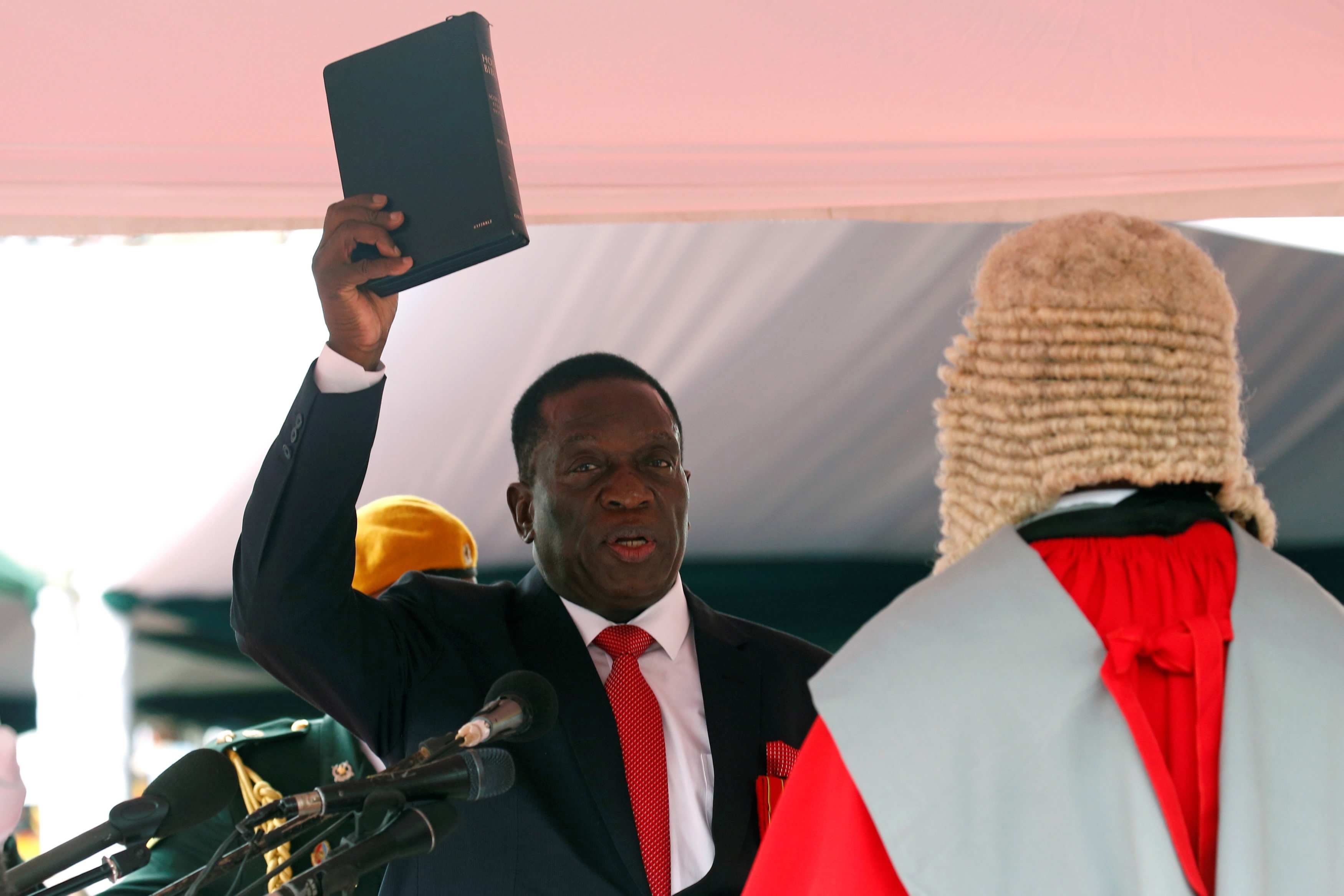

Emmerson Mnangagwa (L) being sworn in as president in Harare, on November 24 /AFP Photo

Emmerson Mnangagwa (L) being sworn in as president in Harare, on November 24 /AFP Photo

Though there is talk about a collapse of the Zimbabwean economy, critics are yet to say whether people in other parts of Africa are better off than those in Zimbabwe. In any case, something has to be done to put the economy right. How the new president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, goes about it remains a whole story of its own. He has the choice of handing Zimbabwe to capitalists in which case it would be turned into a neo-colonial state or continue with a self-reliant country – look for foreign investors and partners to grow the economy without dominating the politics of the country.

The immediate prospects for Zimbabwe seem gloomy. But it is not likely that the old policies will continue. The dismissal of Emmerson Mnangagwa from the post of vice president certainly angered him. He will have to chart a new economic and political path.

The economy will need greater attention. Agricultural returns were witnessing a downturn but the Zimbabwean soil remains productive. Many Zimbabweans have fled from its stunning hyperinflation but retain ties to their home country and are well educated – a result of a good system of grammar schools and higher education, one of Mugabe’s few successful contributions. It has good roads. Its legal and judicial systems aren’t the continent’s best, but neither are they the worst.

Emmerson Mnangagwa taking the oath of office as Zimbabwe's president in Harare on November 24. /Reuters Photo

Emmerson Mnangagwa taking the oath of office as Zimbabwe's president in Harare on November 24. /Reuters Photo

Mnangagwa would have to create a new political power base loyal to him. There will be a redistribution of wealth. He will have to reconcile himself with Mugabe loyalists. The opposition now has hopes of making its case. The new president will have to show to what extent he has the interest of the masses at heart.

The end of Mugabe’s one-man rule breeds hope for a people who have not had change for the last four decades.

It is time for hardcore African dictators to stop hiding behind pan-Africanism and quit the stage.

Zimbabwe is likely to get renewed and substantial assistance from China, which invests heavily in Africa but in recent years soured a bit on Zimbabwe as its leader grew senile. Success will require a broader buy-in from Zimbabwean expatriates who have expertise to contribute along with remittances and a devotion to their homeland – and from Western powers, including the United States, which would be wise to leverage aid to encourage free and fair elections and a political infrastructure that discourages either family rule or military intervention.

(Atia Azohnwi is a multi-award-winning African journalist. He’s served as political editor of The SUN newspaper in Cameroon since 2011. His interests also include peace and human rights journalism, as well as issues of insecurity and climate change. The article reflects the author’s opinion, not necessarily the views of CGTN.)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3