By CGTN’s Wang Fan

“He’d still want to help others.”

Last October, 53-year-old Kong Lingfeng suffered a brain hemorrhage at his home in Beijing. He was rushed to the hospital where he was put on life support. Sadly, the doctors declared there was no chance of recovery. Lingfeng left behind his only son Kong Dequan.

Dequan’s parents had divorced when he was in primary school. This meant it was up to him to make the final decisions regarding his father’s body after he was announced dead. Dequan agreed that his father’s organs could be donated.

At 22, Dequan now works as a technician at the China Coal Research Institute. When asked about his father, he said: “My dad was very warm-hearted. He often said to my uncle and me that when he died, he would still want to help others.”

The idea of organ donation was suggested by Dequan’s uncle, Zhang Tieying, and was supported by the family members gathered at the hospital.

“You’ve got nothing left after the cremation. Why not give what’s usable to those who need it?” said Zhang.

Doctors stand in silent tribute to Kong Lingfeng at Beijing Friendship Hospital. (Zhao Lei/CGTN Photo)

Doctors stand in silent tribute to Kong Lingfeng at Beijing Friendship Hospital. (Zhao Lei/CGTN Photo)

Battling the old system

For decades, transplants in China had relied on organs taken from executed prisoners. Then, in December 2014, the country announced that, as of January 1 the following year, it would discontinue the practice.

The change was initiated by Huang Jiefu, a former vice minister of health who is now director of the China National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee. He had been the first to publicly acknowledge what was an open secret, at the World Healthcare Organization conference in Manila in 2005.

“If our judicial system was involved in allocating organs, how could our transplant sector ever become transparent?” Huang said in an interview with Phoenix TV in 2017, “Only once the old entrenched interests are eliminated can a new mechanism be set up.”

Since 2015, Huang has repeatedly stated that as far as he knows, “the old practice no longer exists.”

China’s first national regulation on organ transplants came into effect on May 1, 2007, banning organ trafficking and setting out guidelines for organ donation and transplantation. In an effort to better regulate the system, the health ministry also cut the number of hospitals licensed to conduct organ transplants from 600 to 164.

According to the latest figures, in 2017 a total of 5,146 donors supplied organs after death and 2,342 living donors donated organs to relatives. In all, 16,184 transplants were carried out in China, the second highest figure in the world after the US with 34,771 transplants.

Huang Jiefu, director of the China National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee, attends a news conference during the 2016 China International Organ Donation Conference in Beijing. (Li Jiangsong/Visual China Group Photo)

Huang Jiefu, director of the China National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee, attends a news conference during the 2016 China International Organ Donation Conference in Beijing. (Li Jiangsong/Visual China Group Photo)

Fair allocation

China began to solicit organs from the public in 2010 when the National Health Commission started the process of building up a centralized organ pool and distribution system, modeled on those in the US.

In April the following year, a national organ-matching platform, the China Organ Transplant Response System (COTRS), went online, charged with ensuring the fair allocation of donor organs.

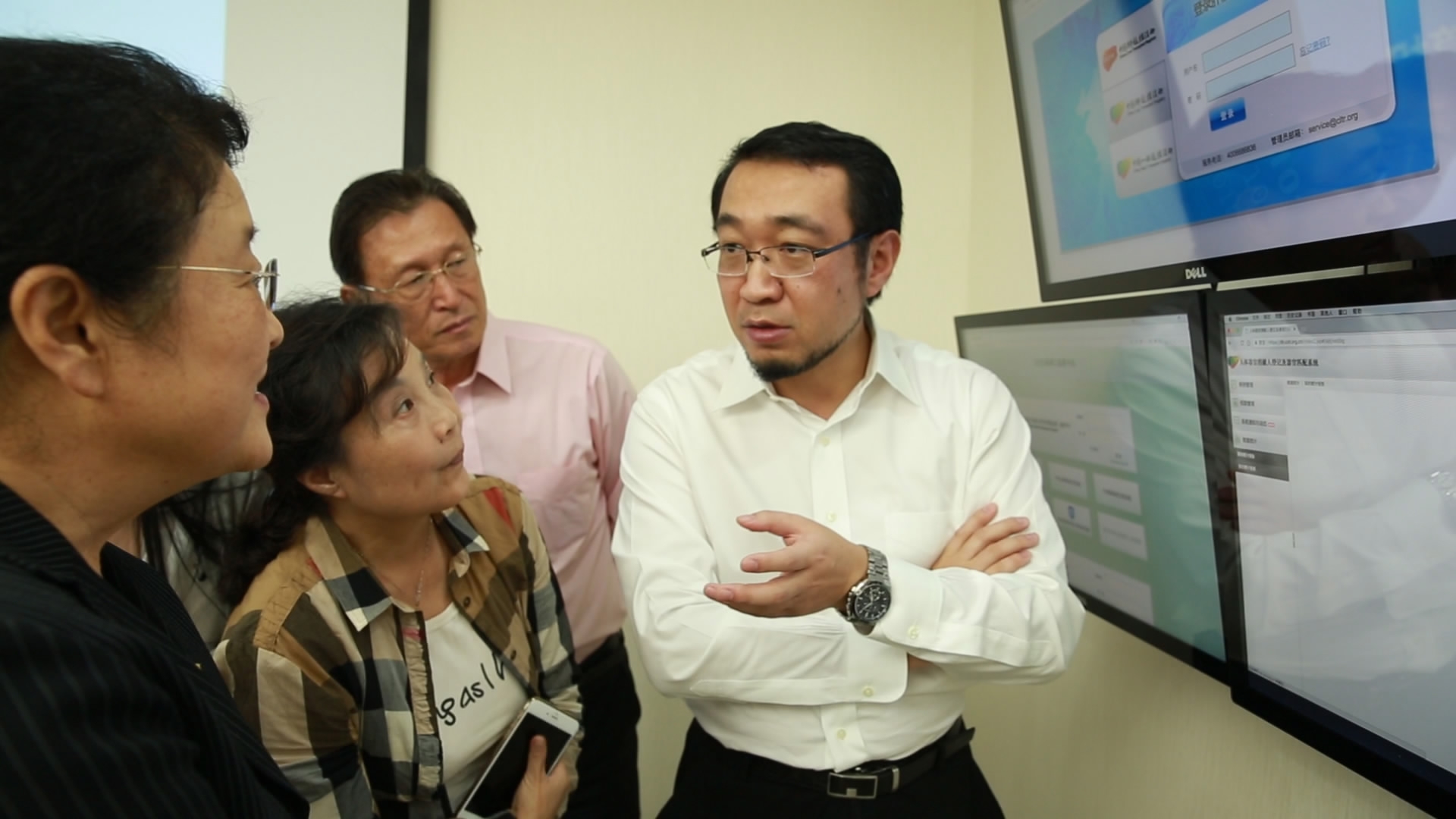

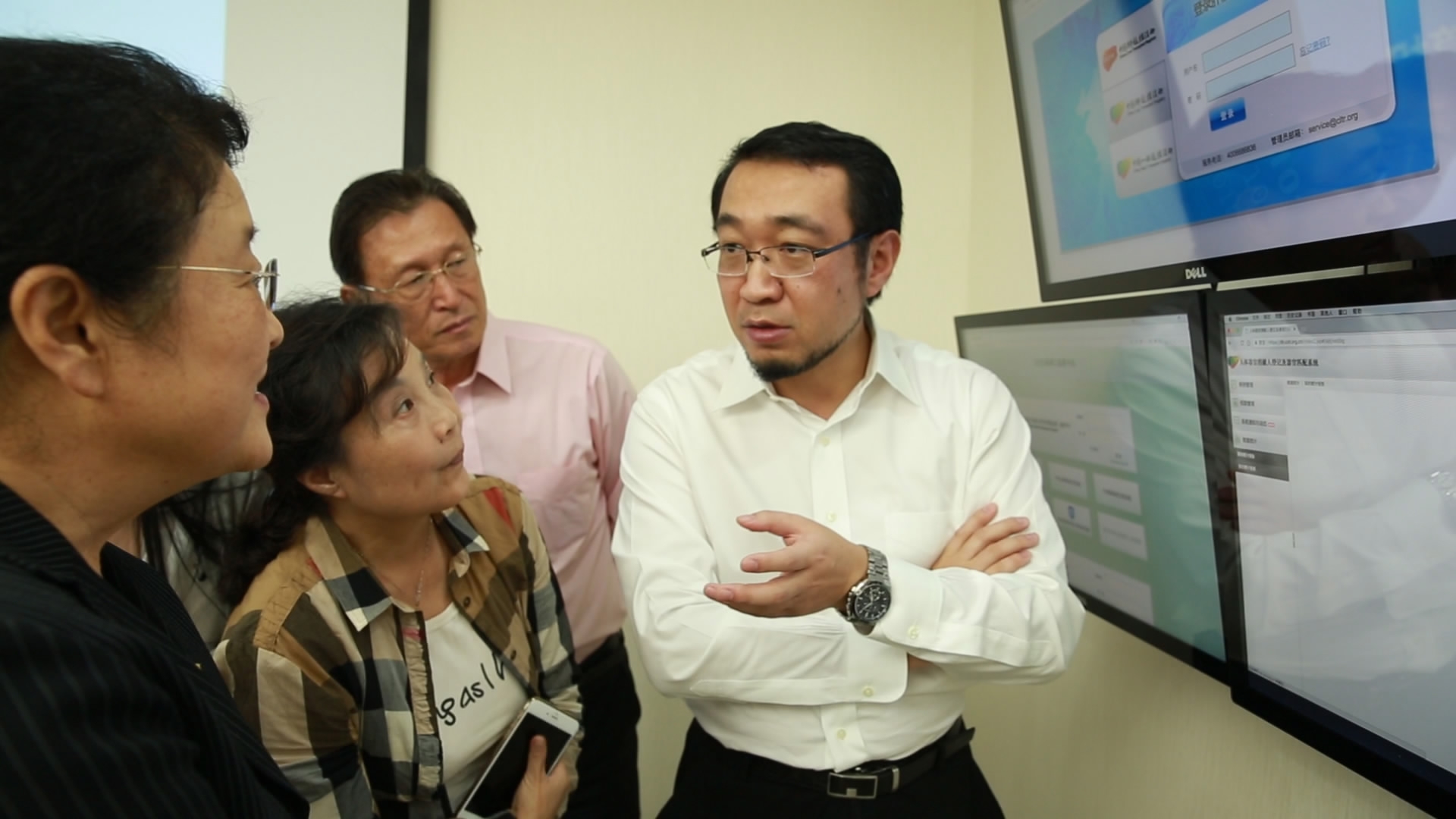

“We’re turning over a new leaf,” said Wang Haibo, the man responsible for designing COTRS. “Nationally, an average of 40 organs are allocated each day.”

"Transplants should not be a privilege for the rich," Huang said in

an interview with China Daily in 2009.

Even so, all costs are passed on to the patient, with a recipient currently paying an average of 635,000 yuan (100,000 US dollars) for a cadaver liver transplant, excluding post-operative care and rehabilitation costs.

Wang and his team are aware that if the allocation is not seen to be fair, people are unlikely to donate their organs.

“It’s based on national policies, hundreds of pages long, that describe what medical needs are,” said Wang. “In a nutshell, we pull back whoever is the closest to death.”

But getting the system up and running was initially challenging. The hardest time was from the end of 2014 until the end of 2016, when national funding had yet to come through. Wang saw his team shrink from 40 to 20, as he couldn’t even pay their salaries.

“The pressure was incredible,” he said. “Everyone had to work overtime because we couldn’t shut down our system even for a minute.”

They made it through, thanks largely to a financial contribution from the China Organ Transplant Development Foundation. A national fund of 20 million yuan (3.2 million US dollars) was eventually put in place at the beginning of 2017.

“With it, we’re building a monitoring platform based on COTRS,” said Wang.

According to Wang, all provincial health commissions are now using the platform.

However, there have been cases of the allocation system being circumvented. Some organ procurement organizations have been guilty of obtaining organs for transplant without proper authorization and inputting the allocation data after the event.

“This is prohibited unless you have sound medical reasons,” said Wang. “What’s holding us back now is the old system. But reforming it is incredibly difficult.”

Wang’s team has compiled a report of all the irregularities it has observed through COTRS and is reporting them to the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

“This is absolutely not allowed,” said Du Bing with medical affairs and administration at the National Health and Family Planning Commission. “We will take appropriate action.”

Wang Haibo introduces COTRS to officials from the China Organ Transplant Development Foundation. (Li Liang/CGTN Photo)

Wang Haibo introduces COTRS to officials from the China Organ Transplant Development Foundation. (Li Liang/CGTN Photo)

Top-level mechanism

Another concern for Wang is the lack of legal status for COTRS, which was established after the 2007 regulation, was adopted.

“Voluntary donation wasn’t included in detail in the initial regulation,” he said. “The regulation must be amended urgently… What we are lacking is a top-level structure from the State Council. Our technology is useless if it’s not supported by a sound mechanism.”

“It has been really tough over the past years,” said Huang Jiefu, commenting on the reform he is leading. “China’s new organ transplant system is still in its infancy.”

In a 2017 interview with Global Times, Huang said, “The obstacle has never been the Chinese culture, nor to motivate or educate our people. What’s pressing is how we can better integrate different departments concerned.”

The National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee only works with two departments: the National Health and Family Planning Commission and the Red Cross. According to Wang Haibo, a priority in any further reform aimed at improving the system is the participation of other agencies.

Wang, a graduate in clinical medicine from Sun Yat-sen University, was once a student of Huang’s. The two men have attended numerous global medical conferences together, where they often find themselves defending China’s organ transplant system from criticism by their international counterparts.

“I never thought it could be this difficult,” said Wang. “Both nationally and internationally.”

His sentiments are echoed by Huang, who wrote in a recent text message to his protégé: “Haibo, there’s still a long way to go.”

Wang Haibo prepares for a meeting with transplant experts in his office in Shenzhen. (Li Liang/CGTN Photo)

Wang Haibo prepares for a meeting with transplant experts in his office in Shenzhen. (Li Liang/CGTN Photo)

The donor’s legacy

Kong Lingfeng’s kidneys were successfully matched to two patients suffering from renal failure, one from Beijing and the other from Henan Province, Central China’s Yellow River Valley.

Both patients had been waiting for a kidney for over three years and had been dependent on dialysis to stay alive. Thanks to Kong’s kidneys, they can now expect to lead a relatively healthy life.

As for Kong’s family, they laid his ashes quietly to rest in a natural burial plot in a tranquil park in the Beijing suburbs.

Kong Lingfeng’s ashes are buried in suburban Beijing. (Li Liang/CGTN Photo)

Kong Lingfeng’s ashes are buried in suburban Beijing. (Li Liang/CGTN Photo)

Rediscovering China is a 30-minute feature program offering in-depth reports on the major issues facing China today. It airs on Sunday at 10:30 a.m. BJT (0230 GMT), with a rebroadcast at 11:30 p.m. (1530 GMT), as well as on Monday at 8:30 a.m. (0030 GMT) and Friday at 1:30 p.m. (0530 GMT).