Forget the rhetorical sparring, impeachment calls and incendiary tweets, the underlying state of the economy historically tips the balance of a U.S. presidential election.

While President Donald Trump continues a campaign strategy focused on immigration, walls and division, past evidence suggests it is economic performance in the year of the election that carries the most weight when voters go to the polls.

"Voters won't be thinking about four years of economic performance when they assess the economy in November 2020," Brad Schiller, emeritus economics professor at American University, recently wrote in the LA Times. "They will be thinking about conditions earlier in the year."

Maintaining positive economic numbers in 2020 is not only important to Trump's re-election bid, it's critical.

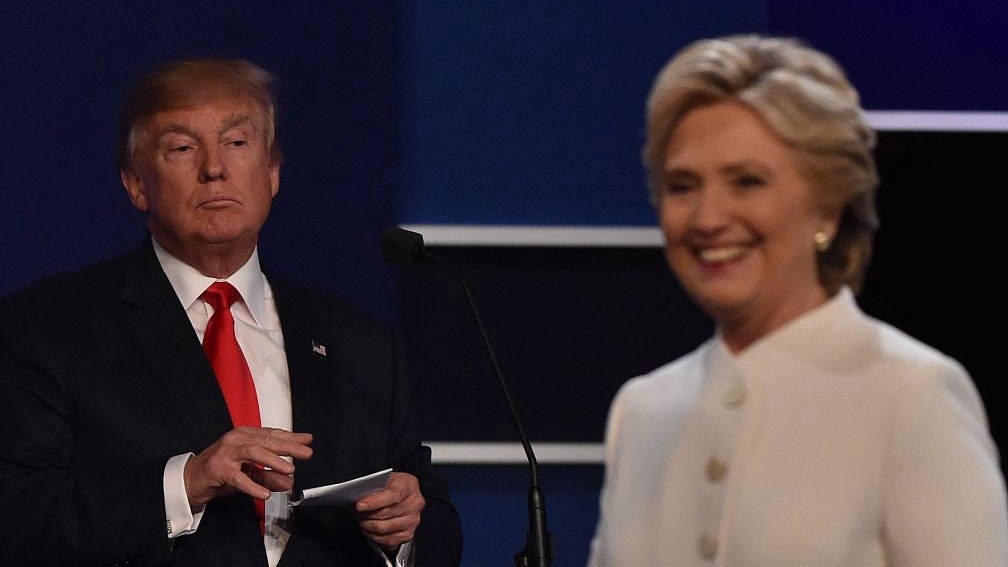

Then Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton departs the stage following the third debate with then Republican nominee Donald Trump at the University of Las Vegas, Nevada, October 19, 2016. /VCG Photo

One of the under-reported factors of the Trump-Clinton clash in the 2016 race was the impact of weaker growth on voter sentiment.

Traditional polling averages indicated Hillary Clinton was the likely winner in 2016, but modelling which incorporated economic data – such as that by political scientist Alan Abramowitz, who has forecast the winner correctly since 1992, and Ray Fair, a Yale University professor – put the Republican ahead (though Trump ultimately won the election despite losing the popular vote).

Growth in the first three quarters of 2016 averaged 1.7 percent, after an Obama-high of 2.9 percent in 2015; a rapid fall in unemployment in 2015 was not maintained in 2016; and job growth peaked in early 2015. The economy was stable in November 2016, but the trend was downward.

Kevin Hassett, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, speaks during a briefing at the White House in Washington, DC, September 10, 2018. /VCG Photo

Trump's time in office to-date has featured positive headline economic numbers. The economy has expanded steadily, significant numbers of new jobs have been created, the unemployment rate hit at a 50-year low and stock markets have reached record highs.

However, there are signs that the Trump year-four economy could look like the final year under the Obama administration.

Growth exceeded expectations at 3.1 percent in the first quarter of 2019 but was over a point down on its peak of 4.2 percent in Q2 2018; the International Monetary Fund forecasts U.S. growth of 2.3 percent in 2019 and 1.9 percent in 2020.

Personal financial security is another danger area. According to a recent Gallup poll, Americans had similar levels of anxiety about their personal finances in April 2019 as April 2016. Forty-nine percent of respondents in the 2019 survey said they had at least one immediate cash-flow concern.

A staff member affixes the presidential seal to a podium ahead of an event to mark the sixth-month anniversary of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passage in the White House in Washington, DC, June 29, 2018. /VCG Photo

A look ahead to the next 12 months also points to a number of broader warning signs, and there remain questions – as Democrat presidential candidates point out – about which parts of society are benefiting from the headline numbers.

The impact of the deregulation policies and massive tax cut plan passed in 2017, a huge stimulus for the U.S. economy, is lessening. And there is growing evidence that those tax cuts are failing to generate the anticipated revenue, creating fresh difficulties: The Bipartisan Policy Center warned on Monday of a “significant risk” that the U.S. will breach its debt limit in early September.

Negotiations over raising the debt ceiling are ongoing in Washington and expected to go to the wire. In the unlikely but not impossible event the talks fail, potential defaults would have a profound impact on the U.S. and global economy. And to-date there appears little interest in managing the one trillion U.S. dollar annual deficit, storing up problems for the future.

There are similar concerns over higher debts and public deficits worldwide, and uncertainty about whether central banks will have the means to respond to another downturn. Interest rates were slashed in the wake of the global financial crisis, for example, and the U.S. rate still stands at under half the pre-crash level of 5.25 percent in July 2007.

Trump blames the Federal Reserve's gradual increase of interest rates for weakening domestic growth, regularly hitting out at Fed chairman Jerome Powell. Rates have risen seven times during Trump's presidency, including four in 2018, but the first cut in a decade is expected at the end of July.

Powell is among the central bankers from the world's biggest developed economies gathering in France this week, with the stability of the global economy a real concern at the G7 meeting amid slowing global growth, the U.S.-instigated trade conflicts and uncertainty over U.S.-Iran relations and the price of oil.

Bank of England governor Mark Carney (1st L), Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell (2nd L) and World Bank President David Malpass pictured ahead of the G7 finance ministers and central bank governors meeting in Chantilly, France, July 17, 2019. /VCG Photo

Trump seems to be repeating the strategy of the 2018 midterms, focusing on wedge issues to appeal to a fervent base of supporters rather than stressing economic progress. The Democrats won those elections, when translated to a national scale, by 8.4 percentage points.

No one has won an election with job approval levels as low as those currently scored by Trump, though those numbers have inched up to an average of 44.6 percent according to RealClearPolitics and he also had historically low approval ratings when taking the White House in 2016.

Nevertheless, winning reelection with such low approval and in a declining economic environment of his own making would be a tough task.

While the president is unlike any previous occupants of the Oval Office, he is unlikely to win in 2020 by defying historical trends on both job approval and the economy.

Finding ways to maintain growth over the next year is vital to Trump's chances of re-election.

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3