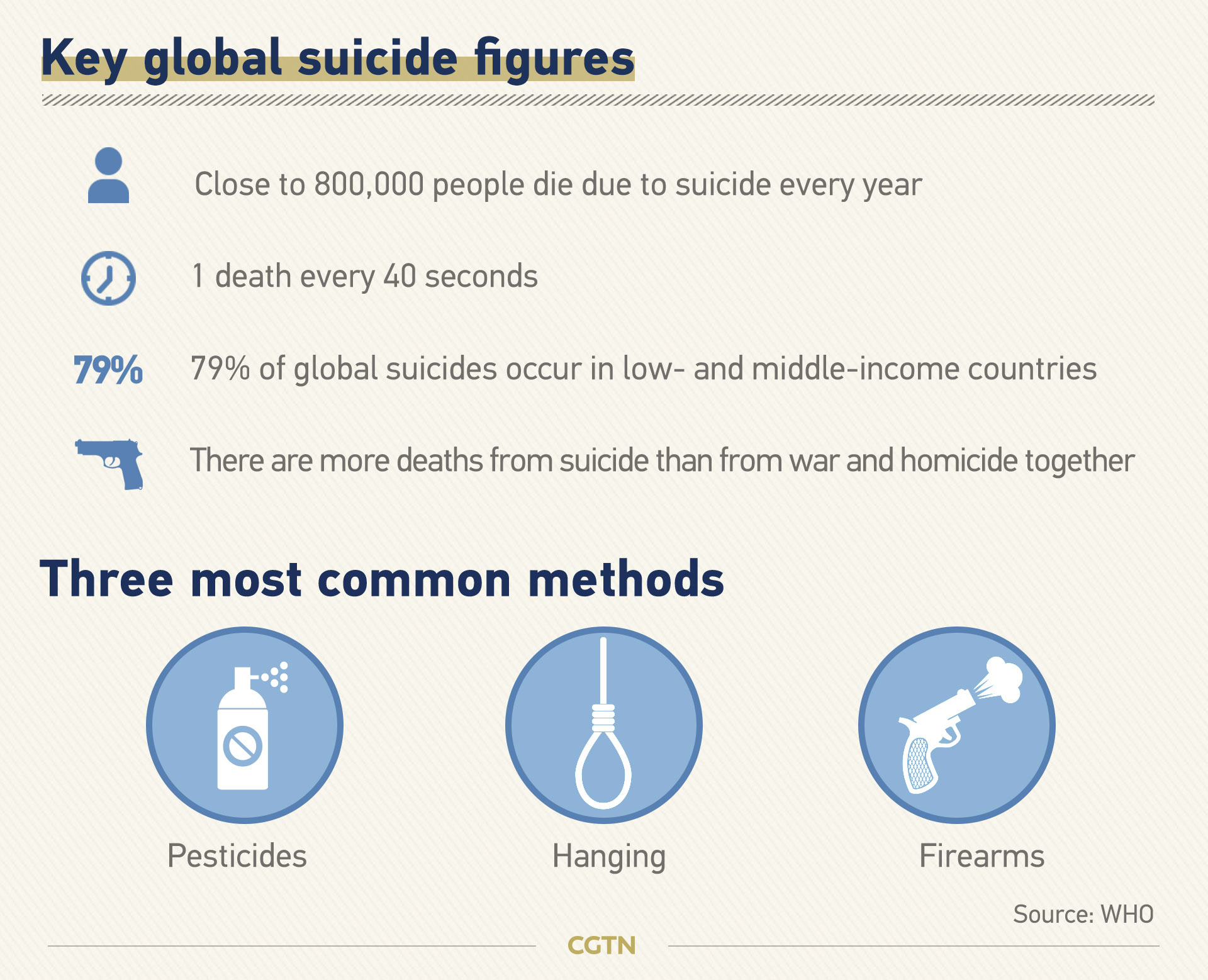

Thursday, October 10 is World Mental Health Day, and this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) wants to draw attention to suicide prevention. Close to 800,000 suicide deaths occur every year, according to the WHO.

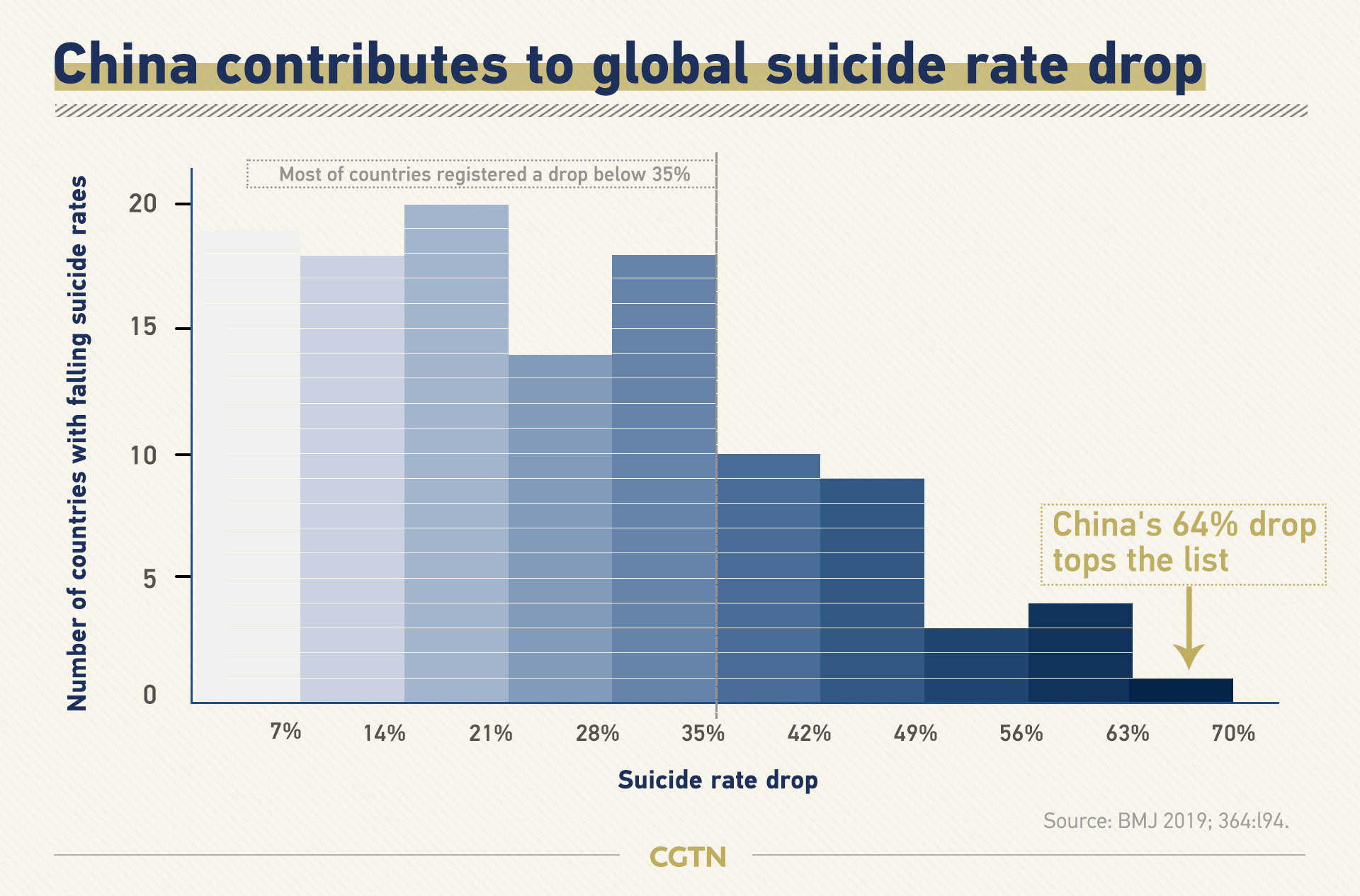

Global suicide rates have decreased by over 30 percent from 1990 to 2016, a study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in February this year has shown. And nowhere have the rates dropped more rapidly than in China, where suicide rates fell by more than 60 percent in the same period.

Read more:

China leads the world in suicide prevention

"Much of the global estimated decline is owing to the large decrease in suicide mortality in China during the study period," said the authors.

Other statistics from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) and the WHO also show a significant decline in China suicide rate from its height in the 1990s and 2000s.

Thirty years ago, China had one of the highest suicide rates in the world. Now, its suicides cases are among the lowest in the world – 9.7 people in every 100,000, according to a 2016 WHO report.

What's happened?

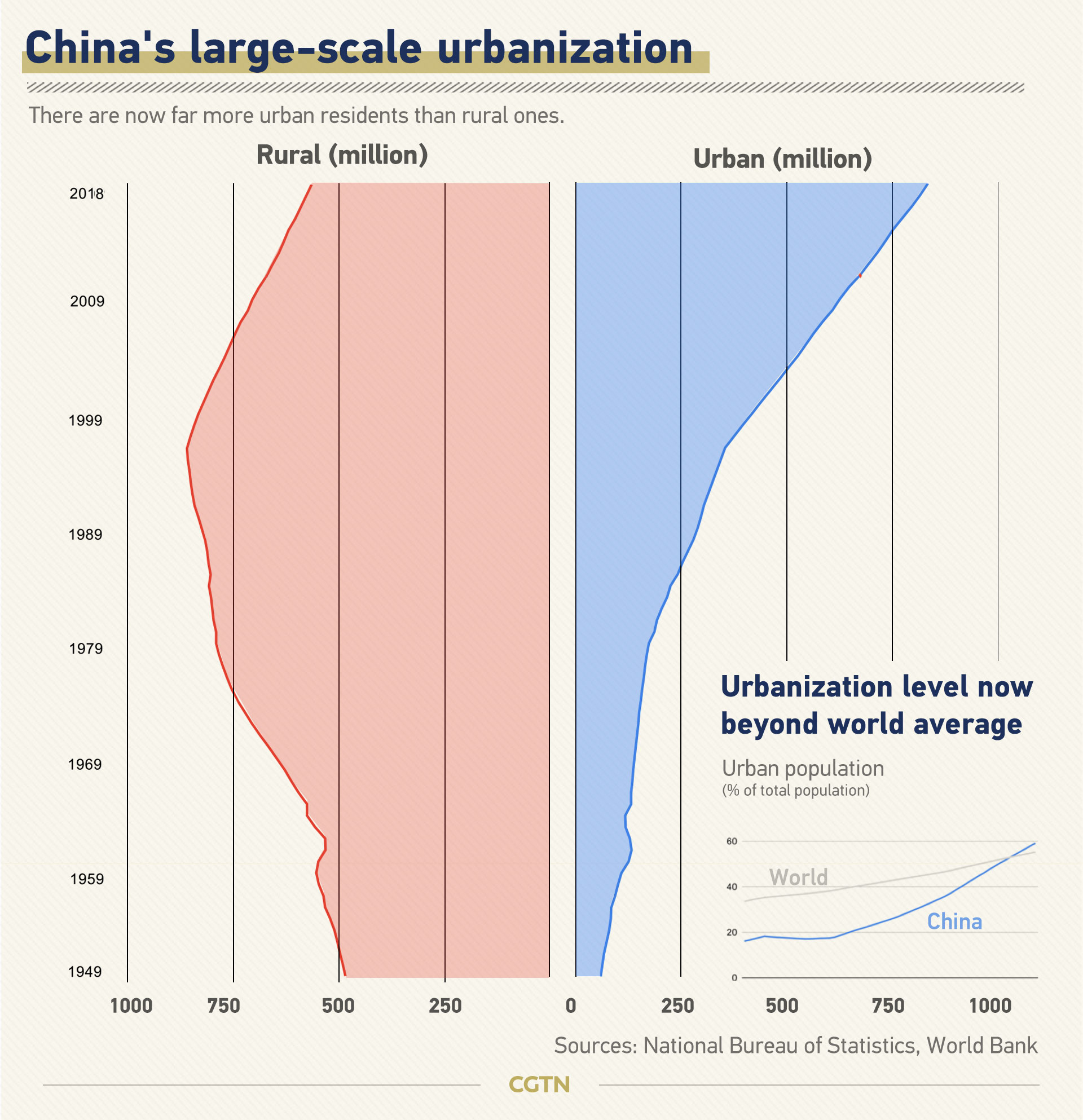

The reasons for China's drop in the suicide rate are often associated with urbanization, improved living standards and reduced access to lethal pesticides.

China's rapid economic development over the past decades has significantly accelerated urbanization.

In rural areas, people are two to five times more likely to kill themselves than in cities, WHO said. Migration to cities often means higher salaries and an improved standard of living for rural Chinese workers.

It also means greater freedom from the social constraints of the countryside, especially for rural women who may experience parental pressures and be in unhappy marriages. A 2002 national survey found that two-thirds of the young rural women who attempted suicide cited unhappy marriages.

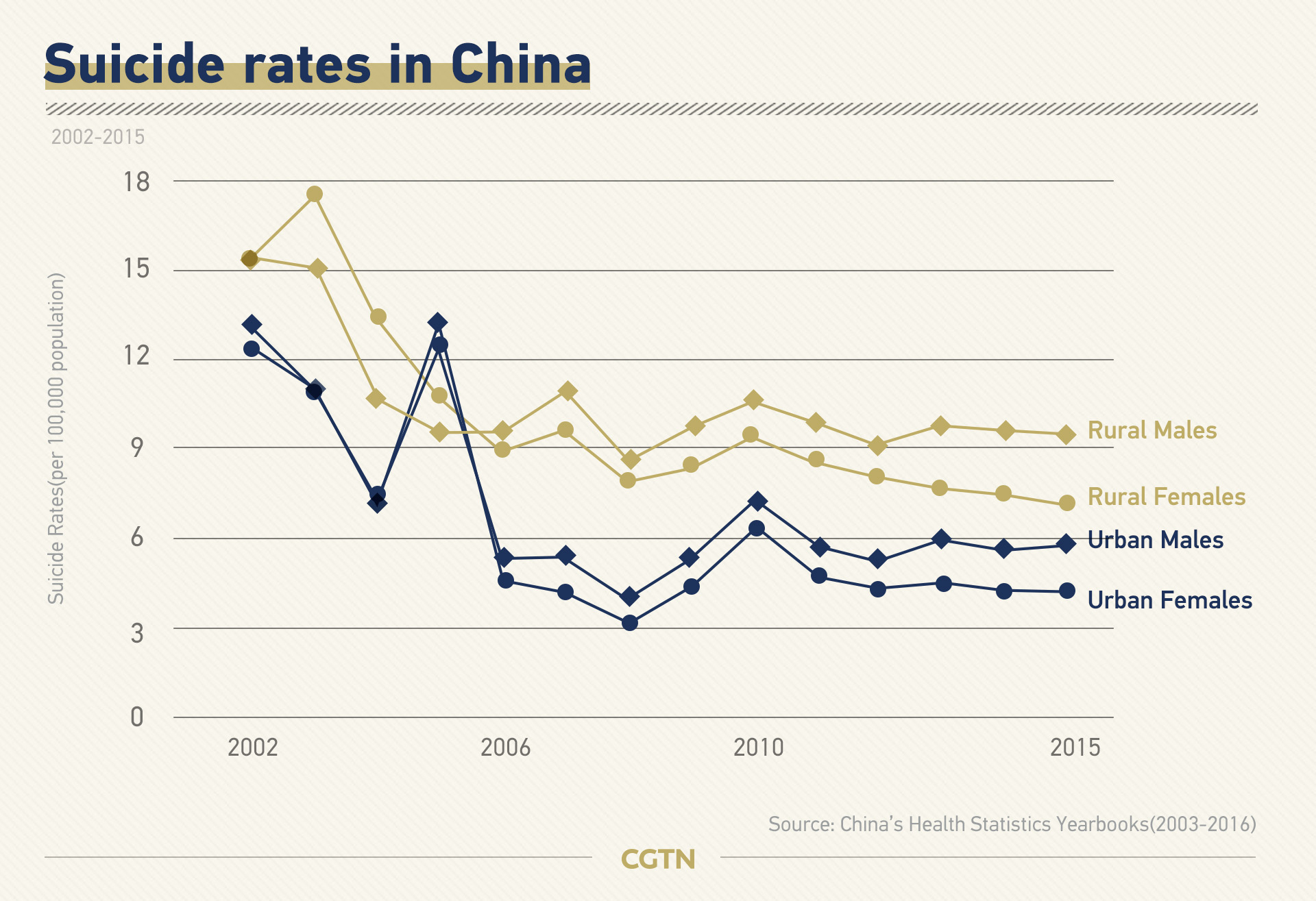

Before, China was one of the few countries with a much higher suicide rate among women than men. Now, the gap between the two has diminished.

Suicide rates among Chinese men and women are nearly equal, with 9.1 suicides in every 100,000 men and 10.3 such cases for women in 2016, according to WHO data.

The decline in rural suicide rates is the major factor behind China's overall suicide rate drop, experts said, noting that fewer suicide attempts among rural women account for the lion's share.

Also, as more people move to cities, their access to lethal pesticides becomes more limited. Ingestion of pesticides, along with hanging and firearms, is the most common method of suicide.

Pesticides were used in 62 percent of the suicides cases in China between 1996 and 2000 (around 175,000 cases per year), the WHO said.

The problems left

Western studies often suggest that economic development and modernization comes with rising suicide rates and incidents of mental illness. Though the current situation in China suggests otherwise, it doesn't mean the benefits will last forever.

In March, the first-ever nationwide study of China's mental health was published in the Lancet Psychiatry journal. The findings suggest that mental disorders are on the rise in China.

The study estimated that about one in every six Chinese had experienced mental illness during their entire lifetime.

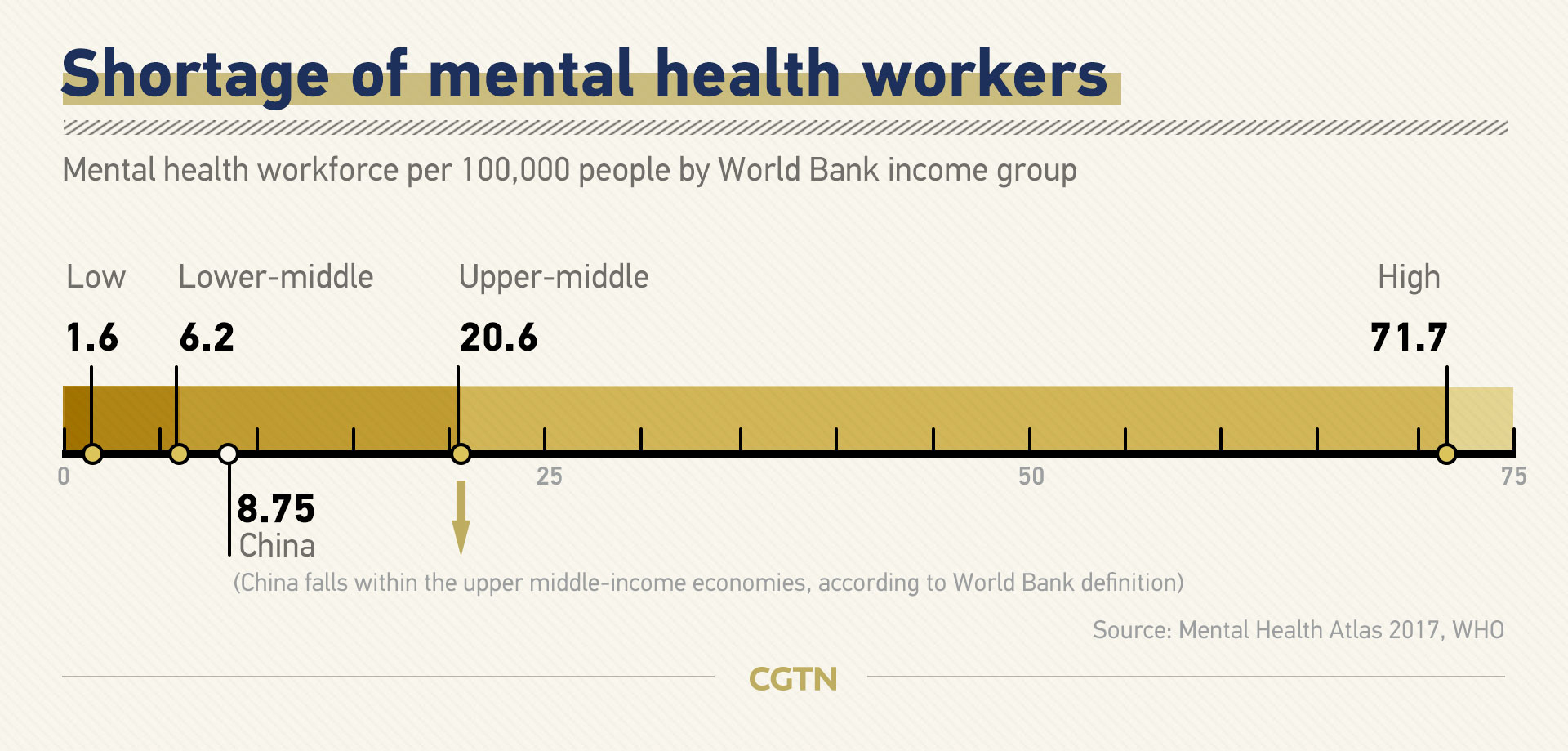

However, psychiatric resources remain in short supply in China. The country has 8.75 mental health worker for 100,000 people, which is not only lower than the global average of 9 but also far below the figure of other upper-middle economies.

What makes the situation worse is that a lot of people have trouble speaking about their mental health problems, said Yuan Li, who works as a counselor and lecturer at the Chinese Association for Mental Health.

"People tell me they feel frustrated, but they don't know how to put that in words – there's a darkness inside them, and they don't know how to take it out. People in China hardly confine their secrets or their feelings to others. Trust is a problem," he told CGTN Digital, adding that many people also fear the social stigma surrounding mental illnesses and suicide.

"People are afraid that when their boss knows about this, they will be fired," he said.

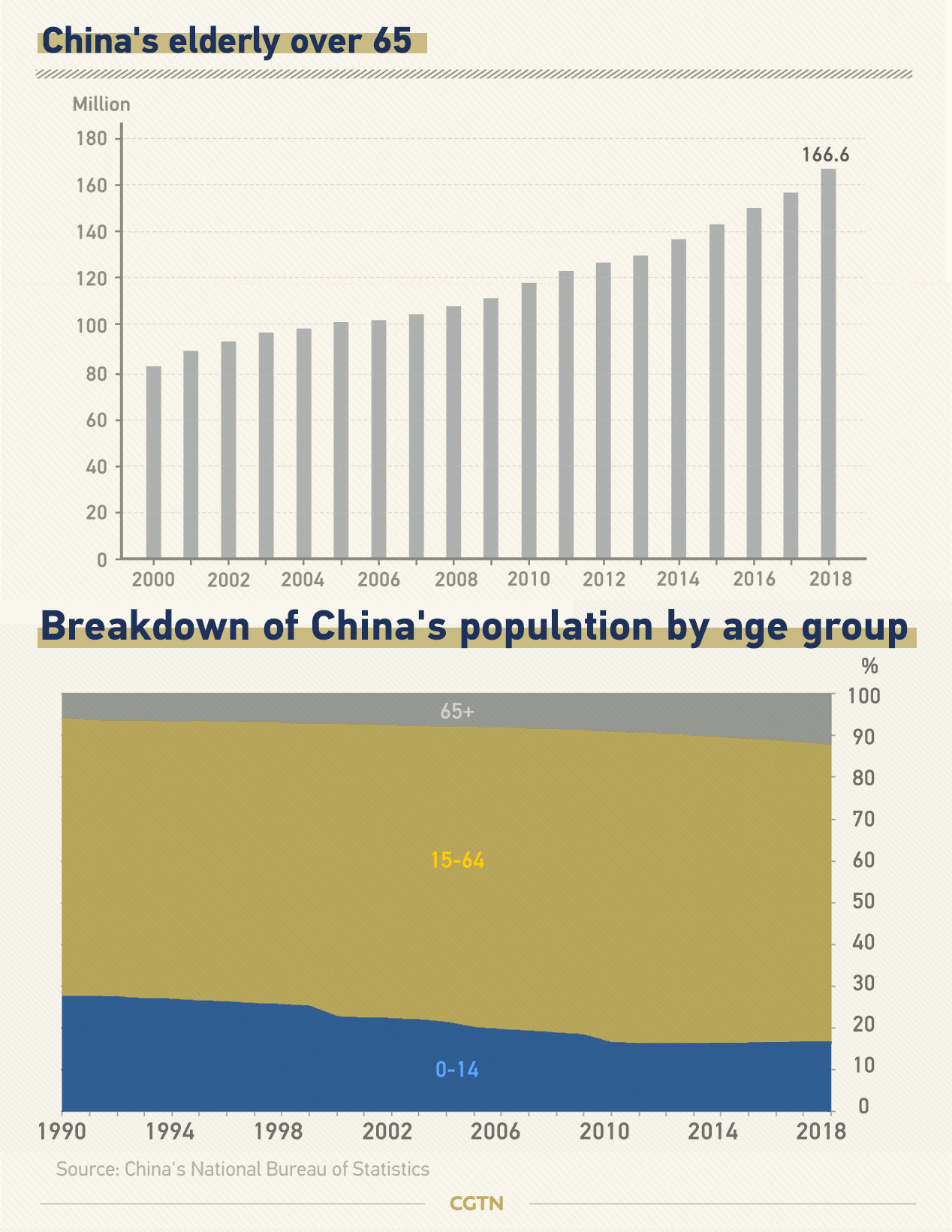

China's aging population also poses another problem. The suicide rate among people 65 and older is up to seven times higher than that of the rest of the population, according to a Caixin report last year.

By the end of 2018, Chinese over 65 accounted for 11.9 percent of the national population. The figure is also expected to rise in the years to come.

The efforts

China is eager to prevent more deaths from suicide. The government, private sector, NGOs, healthcare professionals and civil society have come up with initiatives to reach more people with mental health education and services.

China passed the first mental health law in late 2012. In 2015, the government announced a national five-year mental health work plan, stating clear targets to develop the mental health sector by 2020.

The goals include, for example, that the shortage of mental health professionals should be mitigated, and publicity about mental health and psychological well-being should be spread in hospitals, schools, companies, and institutions to increase societal awareness.

In recent years, and to meet the growing demand as awareness about mental health increases, new services have emerged online as well.

The app Jiandan Xinli, or Simple Psychology," matches people with online counselors and therapists. China Daily reported in 2018 that a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Science set up an AI account on Chinese social media platform Weibo to directly reach out to people who express suicidal thoughts online because only 20 percent of people with suicidal intentions are willing to seek help.

There is also the option of free national suicide helplines that operate 24 hours a day. However, according to Yuan, some of the numbers are incorrect, while others are understaffed, which leads to people spending five to 10 minutes waiting on the line.

"People who really feel they are going through a tough time in life, they have little patience to wait,” he explained.

Yuan said there's still a long way to go to prevent more suicides in China. "A lot of people are attempting suicide (and go unreported), so it's still a tough issue we have to face," he told CGTN Digital, adding that more targeted measures, for example, toward elderly rural men, are needed.

Numbers to call

National Emergency Number in China: 110

China's first free 24-hour hotline for life crisis intervention: 400-161-9995

Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center (24-hour, free hotline): 800-810-1117, 8295-1332

(Graphics: Sa Ren, Li Jingjie)