The U.S. House of Representatives late Tuesday local time overwhelmingly approved the Uygur Act of 2019, a stronger version than the companion bill that the Senate passed in September. The Uygur Intervention and Global Humanitarian Unified Response Act of 2019 urged U.S. President Donald Trump to toughen its response to China's policy in Xinjiang.

The bill was passed in the House after months of deliberation and major changes to harsher rhetoric in demanding sanctions on related authorities and export restrictions. The act is in line with a months-long trend of discontent about China.

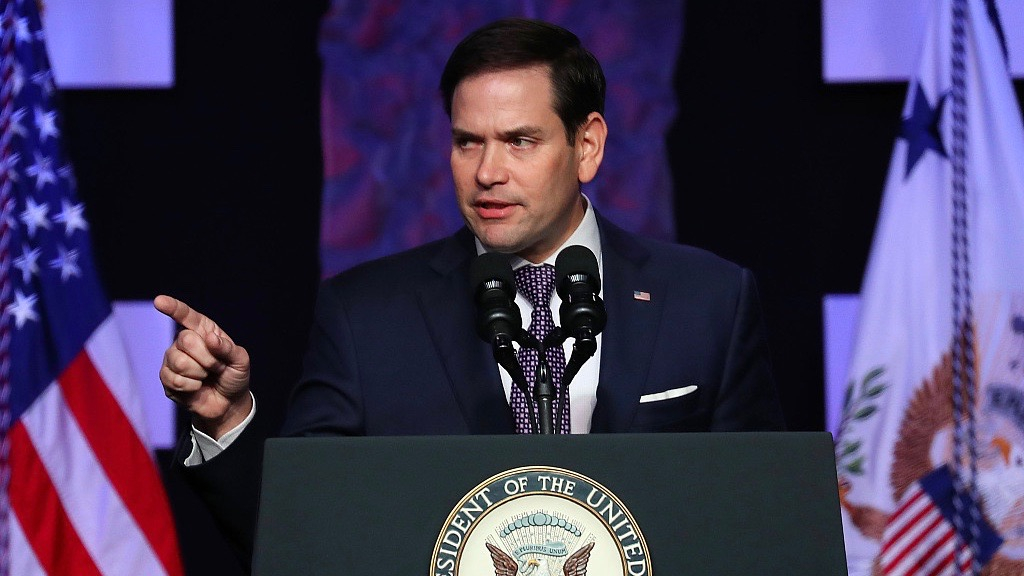

As rioters wreak havoc on the streets of Hong Kong, American politicians have been using legislation to punish China for imaginary practices. But their action on Xinjiang predated the bill on Hong Kong. U.S. senator Marco Rubio, who's behind the "Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act," proposed the bills related to Xinjiang earlier this year with the aim of imposing sanctions on particular Chinese officials, resting on wanton accusations of human rights abuses.

Amid the many political voices in the U.S., Rubio has become the country's unofficial international "ethics chief."

Read more: China expresses strong indignation after U.S. House passes Xinjiang bill

Dancers perform for tourists in Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture of Yili, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, June 29, 2017. /VCG Photo

Dancers perform for tourists in Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture of Yili, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, June 29, 2017. /VCG Photo

As China-U.S. relations walk a diplomatic tightrope, Rubio has come out as a strong Republican voice against the world's second-largest economic power. Although his position seems to be rooted in black-and-white morality, his criticism comes at a time when pressure on China serves as leverage in the ongoing trade negotiations between the two countries. So it's difficult to say whether the senator of Florida is sincere when he tweets statements such as "#HongKong we hear you."

The son of Cuban immigrants to the Sunshine State, Rubio is the golden boy of conservatives in the U.S. Even his political rise was smooth sailing until he dropped out of the 2016 presidential race that saw Trump's upending of conventional GOP wisdom. His rise from a humble background is considered the realization of the American Dream, but fact and fiction have plagued his narrative – much like it has with other high-profile politicians in the country.

U.S. President Donald Trump (C) is greeted by Senator Marco Rubio after arriving to receive a briefing on Hurricane Irma relief efforts at Southwest Florida International Airport in Fort Myers, Florida, U.S., September 14, 2017. /VCG Photo

U.S. President Donald Trump (C) is greeted by Senator Marco Rubio after arriving to receive a briefing on Hurricane Irma relief efforts at Southwest Florida International Airport in Fort Myers, Florida, U.S., September 14, 2017. /VCG Photo

From self-style 'exile' to Washington insider

During his presidential campaign in 2016, Rubio repeated time and again how he hailed from blue-collar parents who had escaped Fidel Castro's Cuba. Many migrants from the country had started anew in Florida, forming a Cuban community that continues to dominate domestic Hispanic politics. Rubio's father worked as a bartender while his mother cleaned hotels – media revealed, however, that his parents left about two years before Castro took power, during Fulgencio Batista's reign in 1956.

It is unsurprising that Rubio tapped into the narrative of the Cuban exile. After all, Cuban Americans in the state who see themselves as being cast out of their homeland constitute a significant voting bloc, one of the few groups in American politics to be compared with Israelis in terms of influence.

Political ambition

His ascension to a Washington insider, then, was predicated on this heritage. Rubio first held public office in a local city commission in 1998 in Miami, the center of the Cuban-American political machine. However, it was his tutelage under a powerful political scion that cemented his rise – Jeb from the Bush family. Jeb Bush was the governor of Florida in 2000 when the Republicans took control of the state, forming a close political relationship with Rubio, who was then-state House representative.

Rubio eventually won the seat for the U.S. Senate in 2010, but quit to join the presidential race of 2016, challenging his mentor Jeb Bush in an initially unexpected move. He dropped out after trailing behind Donald Trump and Ted Cruz.

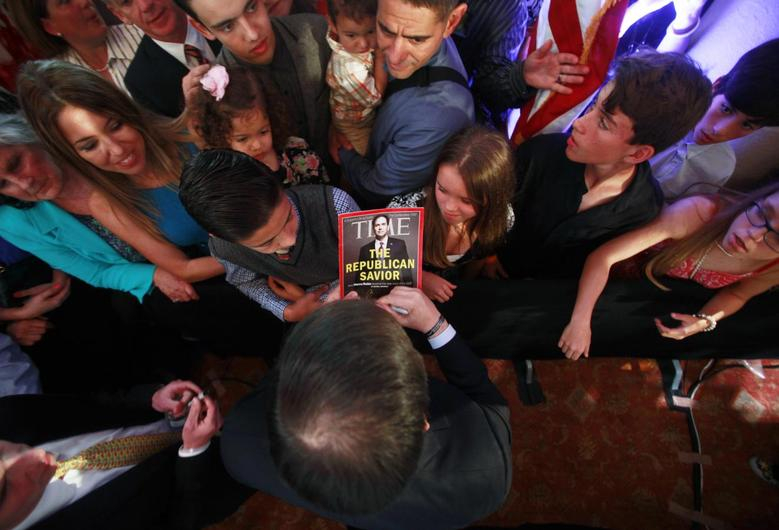

Marco Rubio autographs a magazine after he announced his bid for the Republican nomination in the 2016 presidential election, during a speech in Miami, U.S., April 13, 2015. /Photo via Reuters

Marco Rubio autographs a magazine after he announced his bid for the Republican nomination in the 2016 presidential election, during a speech in Miami, U.S., April 13, 2015. /Photo via Reuters

Conservative, but not completely

The Florida-born Rubio is an exemplar of American conservatism, opposing government-mandated health care, gun control and same-sex marriage. He was even considered a leader of the Tea Party movement that shifted the Republican party to the far right. However, true to his family background and in opposition to the conventional party position, Rubio had supported immigration legislation that opened the door to citizenship for the millions of illegal residents in the country who had met certain conditions. The politically shrewd senator stepped away from the legislation after support from conservatives took a dip.

China angst

Rubio's straightforward narrative seems to justify his every political stance. As the architect of the Senate bills against Hong Kong and Xinjiang, Rubio's outspoken criticism against China may be traced back to his Catholic faith, which he rediscovered after converting to Mormonism. As such, his binary sense of morality seems to partially explain his crusade against the rising economic powerhouse, but comes during a convenient period for China-U.S. trade negotiations, during which external pressure on China can be used as leverage for U.S. Trump.

Rubio said in an interview with CNBC that he's not "anti-China, but [the U.S. needs] a fair and balanced relationship." At a time when bilateral relations are deteriorating, his allegations have a nice ring of morality, but it is difficult to separate this justification from the general fear of China's rise in U.S. mainstream politics.