Pangolins are often sought after for their meat and scales. /AP Photo

Pangolins are often sought after for their meat and scales. /AP Photo

The novel coronavirus outbreak has thrust the Chinese culinary practice of eating "wild game meat" into the spotlight. The epidemic has killed more than 400 people and infected more than 20,000 in China, already surpassing numbers during the SARS outbreak in 2003.

Scientists and health experts have traced the pneumonia-like disease to a Wuhan seafood market, where a wide range of live wild animals were slaughtered on site and sold for their meat. It is believed that the virus was originally carried by bats and transmitted to humans via an intermediate animal host – one likely sold on the market and then eaten by human.

This was also the case with the SARS outbreak, which has been blamed on eating civet cats in parts of southern China. Now, hit by another deadly epidemic linked to wild animals, the country is angrier than ever at those responsible for unleashing it.

Backlash against 'game meat'

On January 26, China announced a temporary ban on all wild animal trade and has stepped up law enforcement on wildlife-related criminal activities. The move was welcomed by animal advocacy groups and the public.

"We hope that this courageous step is made permanent and extended to all wildlife imports and exports, to help prevent any future crises of this nature," said Kate Nustedt, global wildlife director of World Animal Protection.

There have also been calls for a permanent ban on wildlife trade across different sections of society. Last week, 19 Chinese academics and scholars jointly called for lawmakers to amend the country's wildlife law to address public health and safety and outlaw wildlife consumption.

Chinese mainstream media also launched social media campaigns along the lines of "Control your appetite, say 'no' to game meat!" ahead of the Lunar New Year to highlight the dangers of eating wild animals.

A search for "game meat" on the Chinese search engine Baidu now returns with a reminder for people to safeguard the health of their families by avoiding such meat. Meanwhile, more articles, photos and videos explaining the dangers of eating wildlife were published on the platform over the past week than in the last ten years combined.

"Be in awe of nature, or be punished" is now the most echoed voice from Chinese social media users, who urged others to reflect on the cause of the outbreak.

As an old Chinese saying goes, "Disease enters through the mouth." But when it comes to gluttony, some are always ready to overstep commonsense on food safety.

Statistics show that more than 70 percent of emerging infectious diseases have been caused by pathogens originating from animals or their products. Deadly diseases including HIV, Ebola, MERS, SARS, bird flu and now the coronavirus all made the leap from wildlife to humans.

China's top SARS expert Zhong Nanshan warned in 2010 of a similar outbreak caused by the wildlife trade.

Shi Zhengli, director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, sounded the alarm in 2018 that another SARS-like outbreak was possible if people were not vigilant.

"Preventing a new infectious disease from its source is simple – stay away from wild animals," Shi said.

After the 2003 outbreak, consumption of civet cats reportedly declined for a few years, but quietly revived later.

The Wuhan coronavirus outbreak just confirmed experts' worst fears.

Caged civet cats on display in a wildlife market in Guangzhou, south China's Guangdong Province. /AP Photo

Caged civet cats on display in a wildlife market in Guangzhou, south China's Guangdong Province. /AP Photo

Do the Chinese really eat everything?

The ongoing public health crisis, declared a global emergency by the World Health Organization, has dealt a major blow to China's international image. Videos of Chinese women eating bats have gone viral around the world following the outbreak and reinforced the widely held view that Chinese "eat everything."

Some international media have played up the stereotype by claiming that bat soup is a popular dish in Wuhan region. That is not true at all.

A Chinese travel show host recently had to apologize to the public over a three-year-old video showing her eating a bat in the South Pacific country Palau, where it is considered a normal dish. The rise of live-streaming is believed to have driven some influencers to devour unusual "delicacies" on camera for the spectacle, while giving "shocking" dishes greater exposure.

With coronavirus in the news, stomach-turning videos of individuals eating live animals have surfaced on social media, triggering moral outrage toward the animal cruelty and fueling anti-Chinese sentiments in other countries.

In reality, whether it is eating dogs or eating bats, such practice is not nearly as commonplace as they are made out to be. It is true though, that some wild animals like civet cats and bamboo rats are more commonly eaten in some regions than others in China.

Big data revealed that in the last ten years, porcupine and pangolin are the most sought after wild animals for their meat, making up nearly 50 percent of all searches for exotic food. Bats and civet cats, the culprits of SARS, also contributed 15 percent and 8 percent of related searches respectively.

Nevertheless, the mainstream view in China remains that eating wild animals is the acquired taste of a few.

The use of wild animals and their parts for food and medicine is rooted in the ancient belief of their health benefits, like boosting male virility. Although the medicinal claims have little scientific basis, those perceived benefits have survived and thrived in modern imagination.

An unofficial online survey found that around half of those who sought after game meat believe wild animals have more nutritional values than domesticated ones – another myth that's been debunked by scientists. Meanwhile, a sizable number of respondents saw dining on rare animals as a way to flaunt their wealth.

Dr. Peter Li at the University of Houston-Downtown, a China policy specialist at Humane Society International who researches animal protection in China, has called eating wild animals a "regression" of the country's food culture.

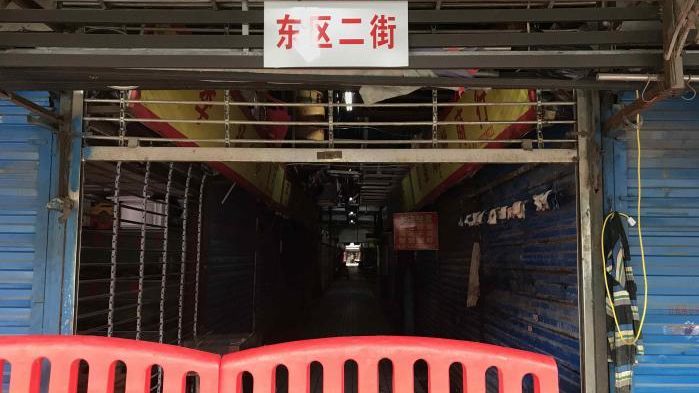

Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, where the coronavirus outbreak began in Wuhan, has been closed since early January. /Chinanews Photo

Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, where the coronavirus outbreak began in Wuhan, has been closed since early January. /Chinanews Photo

Is wildlife protection law enough?

China's Wildlife Protection Law, adopted in 1988, permits the domestication and breeding of wildlife under state protection with a license issued by the State Forestry Administration. In 2003, the administration allowed 54 wild species to be bred on farms and sold for consumption, including raccoons, minks and sika deer.

The 2016 revision of the wildlife law continues to allow wildlife to be farmed and utilized for commercial purposes. It also allows wildlife to be used in making traditional Chinese medicine, healthcare supplements, and food for profit. For many, this is a lucrative business.

Some experts have noted that the growing industry of captive breeding often undermines conservation efforts, as it has enabled illegal trading and consumption of protected animals in the name of conservation and breeding.

Xie Yan, a researcher at the China Central Academy of Zoology, said the use of wildlife for commercial purposes encourages an attitude that stimulates demand for wildlife products.

China has made building an ecological civilization a key part of its overall development strategy. A guideline issued by the State Council and the Communist Party of China's Central Committee calls for the protection of rare and wild fauna and flora.

Academics, health experts and animal welfare advocates now believe further actions need to be taken.

Calling for a permanent ban on wildlife trade, Li argued in a co-ed for South China Morning Post that the "unsavory trade," which is already responsible for two major outbreaks in China, hurts rather than benefits the country's economy as well as reputation.

"China has to choose between the narrow interests of wildlife businesses and the national interest of public health. It cannot allow a minority of wildlife traders and exotic food lovers to hijack the public interest of the entire nation," he wrote.

Caroline Dingle, a biologist and expert in wildlife crime at Hong Kong University, says educating the public is important.

"People need to believe that consuming wild animals is bad for them personally for any ban to work long-term."