Black Monday returned after 32 years when the Dow Jones industrial average ended the opening day down more than 2,000 points and Wall Street triggered an automated circuit breaker that put trading to a halt. The massive rout triggered by the coronavirus panic swept from London to Tokyo.

In addition to the dramatic financial volatility, the spread of the coronavirus led the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to cut the 2020 global growth to as low as 1.5 percent. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a recession will occur if global growth falls below 2.5 percent a year.

With confirmed coronavirus cases soaring past 110,000 globally, it's difficult to predict the exact losses to the already slowing economy. But a closer look at how epidemics throughout history affected the economy may shed light on the current situation.

The New York Stock Exchange in New York City, New York, U.S., March 6, 2020. /Reuters

The New York Stock Exchange in New York City, New York, U.S., March 6, 2020. /Reuters

Black Death

The Black Death ravaged 14th century Europe as one of the most catastrophic pandemics in recorded history, claiming 75 to 200 million lives in Eurasia. The loss of manpower, somewhere between a third to a half of the European population, greatly changed the medieval agricultural economy, preluding a transition from a commercial revolution to "modern capitalism," according to many economists.

Farmers went from growing grain to cultivating cash crops and raising livestock. Meanwhile, rising wages led to more spending and hence enriched layers of trade networks, which in turn precipitated the invention of industrial machines to meet growing consumption.

Accounting, banking and credit systems also started to modernize at the time to facilitate investment. With market prosperity came economic expansion and an integration of markets.

Red Cross litter carriers transport a victim of Spanish Flu in Washington, DC in 1918.

Red Cross litter carriers transport a victim of Spanish Flu in Washington, DC in 1918.

Spanish flu

As European nations clashed in WWI, governments censored news related to the spread of a deadly influenza virus to avoid affecting the morale of troops fighting during the decisive phase of the war. Spain's neutrality in the conflict allowed reports of the epidemic to surface, which gave the impression that the virus originated in the country, hence the misnomer "Spanish flu."

In one of the deadliest pandemics in history, the influenza of 1918 infected one quarter of the world population and wiped out tens of millions of people – more than the total number of deaths from the war at the time.

Despite its horrendous death toll, the influenza only inflicted a sharp but temporary decline in global economic activity, according to analysis by the IMF. However, this could be due to the wartime preparedness of the countries involved and wouldn't necessarily apply in the peaceful circumstances of today.

As the U.S. joined the war in 1917, massive federal spending was unleashed to support the war effort. Factories switched from producing civilian to military goods while unemployment dropped from 7.9 percent to 1.4 percent as young men from across the country enlisted in the military. As a result, the annual output loss was only 0.4 percent despite the incredible devastation caused by the influenza, according to a study by the Canadian Department of Finance.

Attempts to uncover the real economic consequences of a large-scale pandemic focused on the experience of Sweden – a neutral country during WWI that was nonetheless struck by the 1918 influenza. Joint research conducted by several universities in Europe concluded that the pandemic appeared to lead to a large increase in poverty rates. A 2006 study published in the Journal of Political Economy also found that fetuses conceived during the 1918 influenza showed reduced educational attainment, increased rates of physical disability, as well as lower income and socioeconomic status.

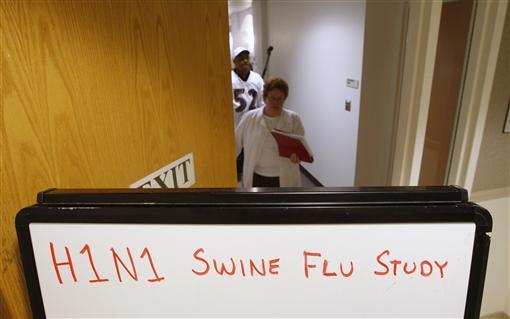

A medical professional leads a volunteer to receive an experimental vaccine designed to prevent him from contracting the H1N1 swine flu virus, during early trials of the drug at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, U.S., August 10, 2009. /Reuters

A medical professional leads a volunteer to receive an experimental vaccine designed to prevent him from contracting the H1N1 swine flu virus, during early trials of the drug at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, U.S., August 10, 2009. /Reuters

H1N1 influenza

The outbreak of the swine flu, or H1N1 influenza, in 2009 caused great alarm at the time. The strain was different from but related to the Spanish flu of 1918 that had killed tens of millions. Experts estimated that the virus in 2009 killed hundreds of thousands in its first year, which made it less deadly, but it still dented the economies of the U.S. and Latin America.

Though direct economic impacts from an epidemic are difficult to model, especially when much of the global economy was in the midst of the Great Recession, certain indicators show that particular industries were negatively affected. Mexico lost almost a million visitors during that time over a five-month period, incurring estimated losses of 2.8 billion U.S. dollars in tourism. Its pork industry didn't fare so well either. Since the country is a major exporter of the meat, trade partners such as China worried about the spread of the swine flu halted imports, a ban that ended only in 2018. By the end of 2009, Mexico's pork trade deficit reached 27 million U.S. dollars.

Socioeconomic burdens more directly related to the disease also attest to the impact of the epidemic. In South Korea, the 2009 H1N1 influenza infected over 3 million people, translating to 1.09 billion U.S. dollars, about 60 percent of which were medical costs. Other costs included lost wages, especially for men, who earned more than women.

The financial burden suffered by the United States can directly be measured by how much money was set aside by the government to fight pandemic flu in 2009, which included H1N1. Congress allocated 7.65 billion U.S. dollars for that purpose. CDC notes that about one million Americans were infected, with 600 deaths.

The global economy shows it's not immune to COVID-19. /Reuters

The global economy shows it's not immune to COVID-19. /Reuters

Now with COVID-19 running rampant, the FTSE100 and Nikkei suffered the worst day since 2008, causing people to worry that the novel coronavirus may take an economic toll like previous pandemics. The gloomy sentiment is, in a sense, well founded. Less than a week ago, the 10-year Treasury yields tumbled below 1 percent – the first time in 150 years since the introduction of the economic benchmark in 1871. And it seems that protective measures against panicked selling en masse fell through this time.

"But this phenomenon is not only related to coronavirus fears but also owing to some fundamental problems in the world's largest economy – prohibitive debts, tax cuts, which further aggravate the debt problems, and financial bubbles," Wang Yong, director of the Center for International Political Economy at Peking University, told CGTN.

There might be a cost to the world real economy in the short term, with supply chains being hit, consumption shrinking and tourism faltering. Plus, "the disease will probably disrupt the cash flow of companies," said Jia Jinjing, director of Macroeconomic Research of the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China. According to Jia, the economy will weather the turbulence and people will have their basic needs met, but unemployment rate might see a slight increase.

Wang noted that today's world is more globalized and advanced than ever before, and more new technologies will emerge to tackle the crisis. As long as countries affected take effective control measures, the coronavirus alone will have little far-reaching economic repercussions.

(Cover image designed by Liu Shaozhen)