Emmanuel Macron marked three years as French president on Thursday as his country began to break out of a strict coronavirus lockdown and look to the future.

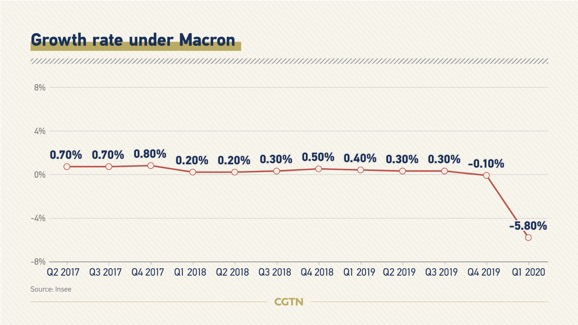

The Macron first term will likely be defined by the impact of the virus and the government response to it over the coming months. France had lost 27,074 lives to COVID-19 since the first reported case in January as of Wednesday, and the economy contracted 5.8 percent in Q1 2020.

France's President Emmanuel Macron during a visit to the Pierre de Ronsard elementary school in Poissy, France, May 5, 2020. /Reuters

France's President Emmanuel Macron during a visit to the Pierre de Ronsard elementary school in Poissy, France, May 5, 2020. /Reuters

A presidency of ambition, reform, protest and occasional scandal has been interrupted with two years to run — and renewal is on the agenda.

"We all face the profound need to invent something new,” Macron told the Financial Times in mid-April, in the heat of the pandemic, "because that is all we can do."

Shaking things up

Macron, now 42, entered the Elysee Palace having upended the political establishment by vanquishing the traditional big two parties in the first round of 2017's presidential election before defeating far-right challenger Marine Le Pen by a two-to-one margin.

Rewind: Could Macron cause an upset?

His nascent movement, then En Marche!, now rebranded La Republique En Marche (LREM), soon won a majority in the National Assembly, the lower house of parliament, drawing in figures from all sides of the political divide.

Edouard Philippe and Bruno Le Maire, formerly Les Republicains, were appointed and remain prime minister and economy minister respectively, while Jean-Yves Le Drian, a member of the previous Socialist government, is still foreign minister three years on.

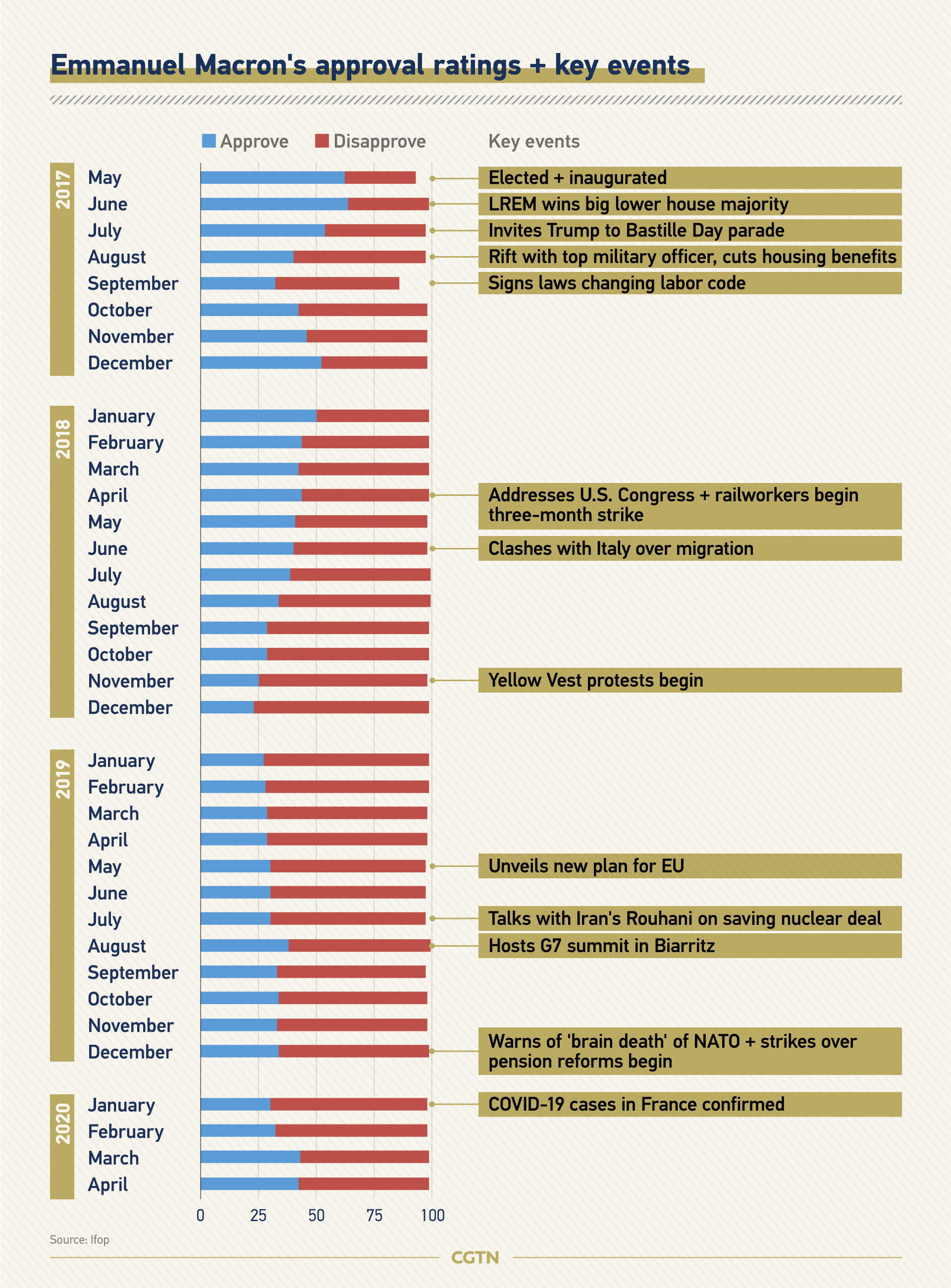

Macron started with a bang and approval ratings were initially high. But while his big tent movement is still standing on firm ground, there have been rocky moments. Within four months the president's ratings were in net negative territory.

Several MPs have quit LREM, and there have been high profile cabinet resignations. MoDem leader Francois Bayrou quit as justice minister in Philippe's government after just a month over a party jobs scandal.

Defections in the National Assembly have seen the party drop to 296 MPs, down from 314 and edging closer to the 289 needed for an absolute majority. It retains the support of MoDem, but there have been rumors of a breakaway grouping preparing to form.

And, unusually, Philippe is running for the mayoralty of his home town, Le Havre, in municipal elections. He says he wants to remain as prime minister whatever the outcome — if Macron wants him.

French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe attends a news conference, Paris, France, April 19, 2020. /Reuters

French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe attends a news conference, Paris, France, April 19, 2020. /Reuters

But two years before the next national and legislative elections, the victories of Macron and LREM continue to reshape the French political landscape.

Les Republicans and the Socialists showed flickering signs of revival in a set of local polls controversially held in March, but nationwide LREM and Le Pen's renamed Rassemblement National are level-pegging and support for ecological parties looks to be growing.

Reform agenda

After Macron's inauguration on May 14, 2017, the then 39-year-old wasted little time in pursuing his plan to reshape the French state and reinvigorate the country's influence on the world stage.

Macron's relationship with U.S. President Donald Trump has alternated between barbs and compliments. But for all the rhetoric, tangible achievements have been rare. Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris climate accords despite Macron's lobbying.

In Brussels, Macron has also face frustration. He sought to lead the drive towards a more integrated and streamlined Europe but his proposals have been largely blocked or watered down.

Domestically, there have been more positive trends. Macron vowed to create an environment for France to become a "start-up nation," make doing business easier and reduce the country's stubbornly high unemployment rate, in part by overturning labor laws.

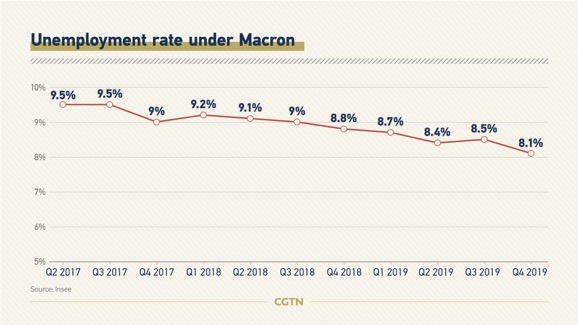

And data from the official Institut national de la statistique et des etudes economiques (INSEE) did indicate progress – until the coronavirus struck.

Unemployment has fallen steadily, from 9.6 percent in Q2 2017, when Macron was elected, to 8.1 percent in Q4 2019, its lowest level since 2008. Youth unemployment (15-24) remains stubbornly high at 20 percent, however.

There has also been broadly positive news on startups. The number of new businesses set up per month in France increased from 47,450 when Macron entered office to a high of 73,036 in December 2019, according to INSEE, before dropping sharply to 51,823 in March 2020 as the pandemic took hold.

He has since announced 300 billion euros of government loan guarantees and put all reforms on hold.

Protest movement

The encouraging trends in parts of the economy have often been overshadowed by opposition and protest, however, with Macron, a former investment banker, often characterized as a "president of the rich."

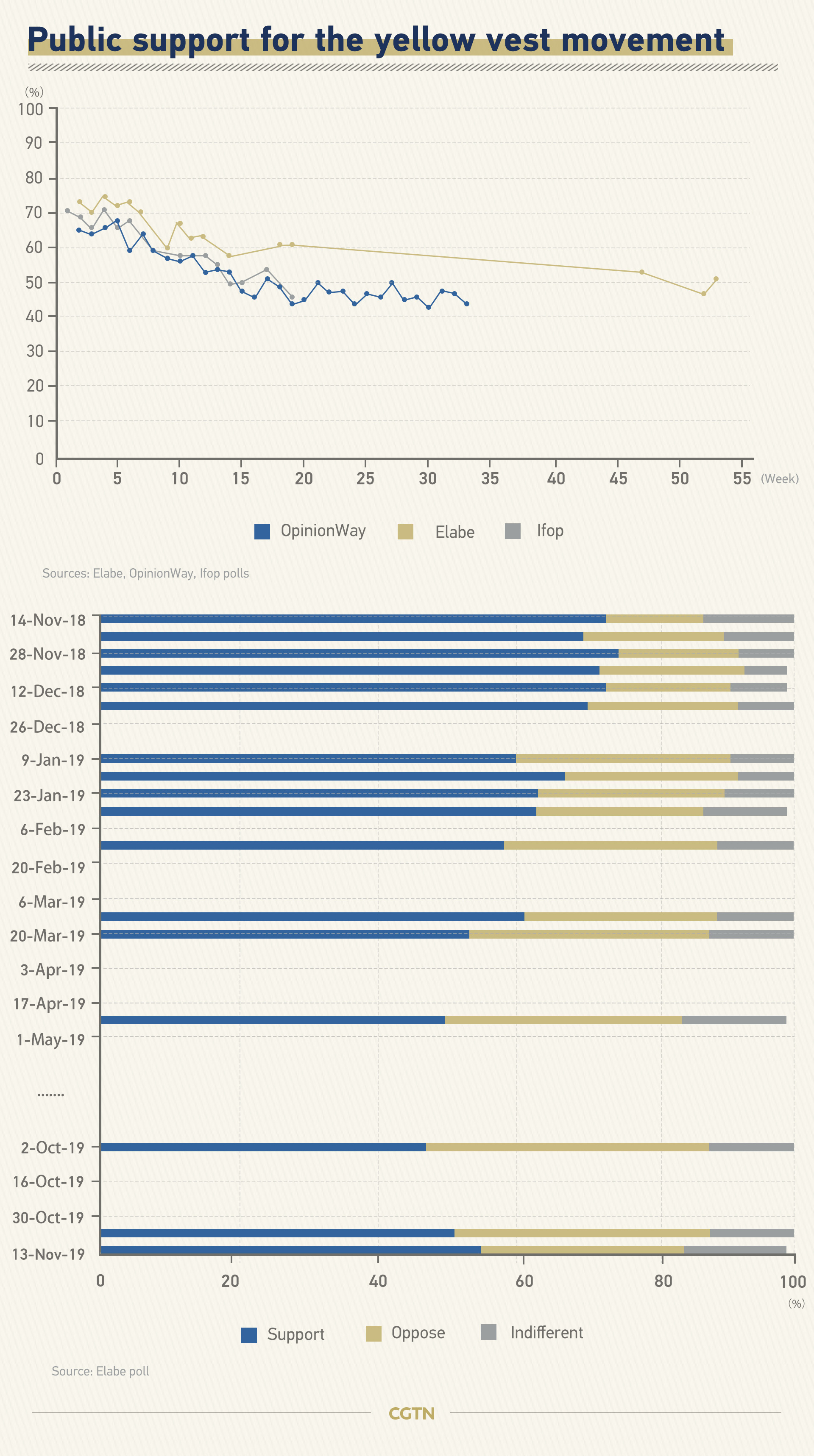

The most prominent example was the months-long gilets jaunes movement, initially sparked by a planned hike in fuel tax, that evolved into widespread demonstrations against Macron's economic policies and the government more broadly.

The tax rise was part of Macron's green agenda, something he is expected to focus on more over the next two years.

Not only does the growing popularity of ecological parties threaten to erode his support, but he told the Financial Times that he anticipates a new approach to the environment in the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

People now understand "that no one hesitates to make very profound, brutal choices when it's a matter of saving lives. It's the same for climate risk," he told the newspaper.

Eventually Macron made significant concessions in the face of the fuel protests. But as public support for the gilets jaunes movement decreased, pension reform proposals provoked a new wave of protests.

Macron wants to abandon existing France's pension system — which involves 42 pension regimes, including different retirement ages — and create a single centralized system.

Transport strikes and rallies brought Paris to a standstill in December and January, as the pension issue again served as a conduit for opposition to the president, whose approval ratings dipped into the 20s.

Seven more years?

COVID-19 has changed everything – months and years ahead will be spent dealing with the fallout and rebuilding the country.

To-date Macron's performance in handling the crisis has received mixed reviews. His approval rating did tick up in March and April but remains in net negative territory, and the government has been accused of flip-flops on mask-wearing and inadequate testing.

39 percent said they trusted the government to tackle the crisis efficiently in a May Ifop poll, down from 55 percent in March.

Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron pose prior to the start of a live election debate, La Plaine-Saint-Denis, near Paris, May 3, 2017. /Reuters

Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron pose prior to the start of a live election debate, La Plaine-Saint-Denis, near Paris, May 3, 2017. /Reuters

Now, as France begins a gradual return towards whatever new normality lies ahead, Macron will have half an eye on the elections that are now less than two years away.

Polls currently suggest a second-round Macron-Le Pen match up is most likely again in the 2022 election. Despite the protests and the low approval ratings, France's youngest president since Napoleon will remain confident of another five years.

"It's a moment to start again from scratch," he said in a speech in April. The man who reshaped French politics is seeking another reinvention as he leads France through the coronavirus pandemic.

Graphics by Chen Yuyang