Editor's note: This is the 72nd article in the COVID-19 Global Roundup series. Here is the previous one.

04:11

As India eases more restrictions, it continues to report record spikes in new COVID-19 infections.

The country reported a record number of daily new infections on Thursday - 9,889 - with 275 deaths - as its tally of fatalities surpassed 6,300 and its number of infections rose to 226,713, the world's seventh-highest. However, the country has reopened on June 1 despite the fact that a peak could still be weeks away.

Back to normal

On Monday, businesses and shops reopened in many states, construction re-started and railways announced 200 more special passenger trains. Some states also opened their borders, allowing vehicular traffic. Soon, hotels, restaurants, malls, places of worship, schools and colleges will also reopen.

The coastal state of Maharashtra, home to the financial hub of Mumbai and Bollywood, allowed the resumption of film production with some restrictions in place. In New Delhi, the capital, authorities announced the reopening of all industries and salons, while keeping the borders sealed until June 8 to try to prevent a spike in new virus cases.

Although social distancing and the wearing of masks in public are still mandatory across India, some people were seen forgoing both in many places. Others violated lockdown rules.

India is roaring rather than inching back to normal. This was expected as two months of lockdown have crippled the economy and left tens of thousands without work.

Migrant workers and their families queue up to get themselves registered for trains to their home states in New Delhi, India, May 26, 2020. /Reuters

Migrant workers and their families queue up to get themselves registered for trains to their home states in New Delhi, India, May 26, 2020. /Reuters

India implemented the lockdown on March 25, ordering everyone to stay inside, except for emergencies and essential services, leading to a sudden halt to the economy. The lockdown was brutally devastating for daily laborers and migrant workers, who fled cities on foot for their homes in the countryside.

According to official data released on Monday, the country's unemployment rate rose to 23.48 percent in May. While, the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a Mumbai-based think tank said it stands at 27.11 percent as for the week ended on May 3, up from the under seven percent level before the start of the pandemic in mid-March.

The think tank added the rate is the highest in urban areas, which constitute the most number of the red zones due to the coronavirus cases, at 29.22 percent, as against 26.69 percent for the rural areas.

"It's certainly time to lift the lockdown," Gautam Menon, a professor and researcher on models of infectious diseases told BBC. He added "beyond a point, it's hard to sustain a lockdown that has gone on for so long - economically, socially, and psychologically."

As India's growth forecast tumbled to a 30-year-low, many voiced that the country needed to open up quickly, and any further lockdowns would be devastating. In May, global consultant McKinsey echoed the opinion, saying India's economy must be "managed alongside persistent infection risks."

According to Indian officials, the initial purpose of the lockdowns is to delay the spike so the nation can get ready by putting health services and systems in place when the spike comes. By now, though grave challenges remain and shortages persist, it seems that Indians have reached the consensus that the government has bought as much time as possible.

In this circumstance, some believe it's time to revive the economy since the choice between a virus that didn't appear to be wreaking havoc yet, and a lockdown that have forced millions of Indians out of jobs, seemed obvious.

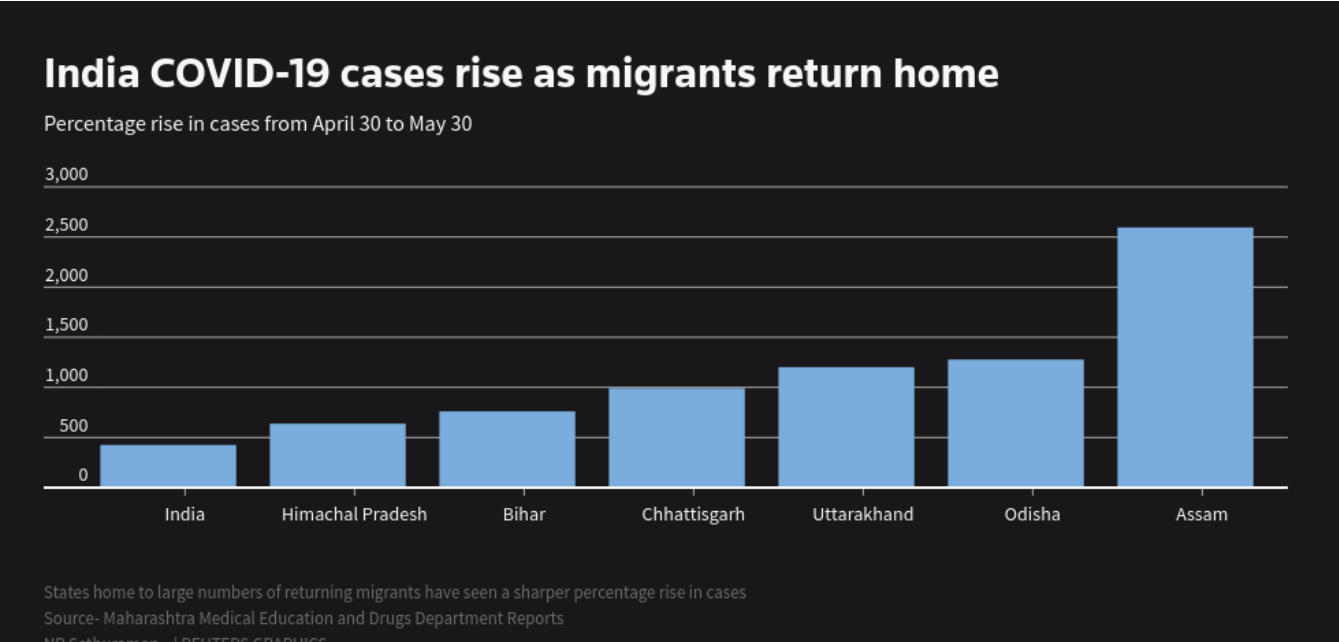

India COVID-19 cases rise as migrants return home. /Reuters

India COVID-19 cases rise as migrants return home. /Reuters

Urban health crisis morphing into a rural crisis

India's strict lockdown has sparked a humanitarian crisis, not only caused by the mass unemployment but also by the government's botched handling of the virus in the initial stage of the pandemic.

The government banned both public and private transport when Prime Minister Narendra Modi placed the country under a sudden lockdown, leaving hundreds of millions of migrant workers stranded in cities across the country battling hunger and government apathy.

With no work, little public transport and fearing they would starve to death in the cities, many attempted to bypass police checkpoints and walked up to 1,000 kilometers to their home villages.

In mid-April, when around 100 million migrant laborers were expecting to be able to travel home, Modi government extended the nationwide lockdown until May 3, triggering protests across India as starving migrant laborers had already burnt through their meager savings and were not receiving any food and money aid from the government. It's reported they were forced to beg and rely on charity for a meal every few days.

It's unknown how many people died because of the lockdown, but the Indian government said keeping Indians indoors has prevented up to 78,000 additional fatalities.

A migrant worker carrying his father on his back gets temperature checked before getting themselves registered for a train to New Delhi, India, May 26, 2020. /Reuters

A migrant worker carrying his father on his back gets temperature checked before getting themselves registered for a train to New Delhi, India, May 26, 2020. /Reuters

As the country began to run trains and buses to reduce the exodus on foot on May 3, allowing millions of migrant workers to go back home, another problem emerged: rural parts of India where medical care is basic at best have begun to see a surge in novel coronavirus infections.

In the eastern state of Bihar, official data showed that of the 3,872 coronavirus cases recorded until June 1, 2,743 were linked to migrants workers who returned after May 3. In Jharkhand, a poor eastern state that borders Bihar, its top health official Nitin Madan Kulkarni said "after May 2, whatever positive cases we have got, almost 90 percent of them are migrant workers."

Dr. Naman Shah, an epidemiologist and physician advising a federal government coronavirus task force, said rural outbreaks could be "devastating" given the inadequate number of doctors and health facilities.

"High levels of co-morbidity, high levels of under-nutrition and a weak health infrastructure, that's just the recipe for high mortality," said Shah, who is based in rural central India.

With nearly 75,000 infections, Maharashtra accounts for a third of the total cases in the country. Officials in some rural districts said their state-run health centers were struggling with the influx.

"If this pace continues for the next few weeks, then we will have no choice but to take control of private hospitals to treat severe patients," one official said.

( With input from agencies )