03:56

A Brazilian research team found samples of the new coronavirus in the sewer system of the southern city of Florianopolis back in late November 2019, three months before the first COVID-19 case was officially recorded in the country on February 26.

Read more: COVID-19 virus found in November sewage water samples in Brazil

The researchers from the Applied Virology Lab at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) published their findings in a paper on June 26. CGTN's correspondent in Brazil, Paulo Cabral, has spoken to two leading researchers on the team for more details about their discovery.

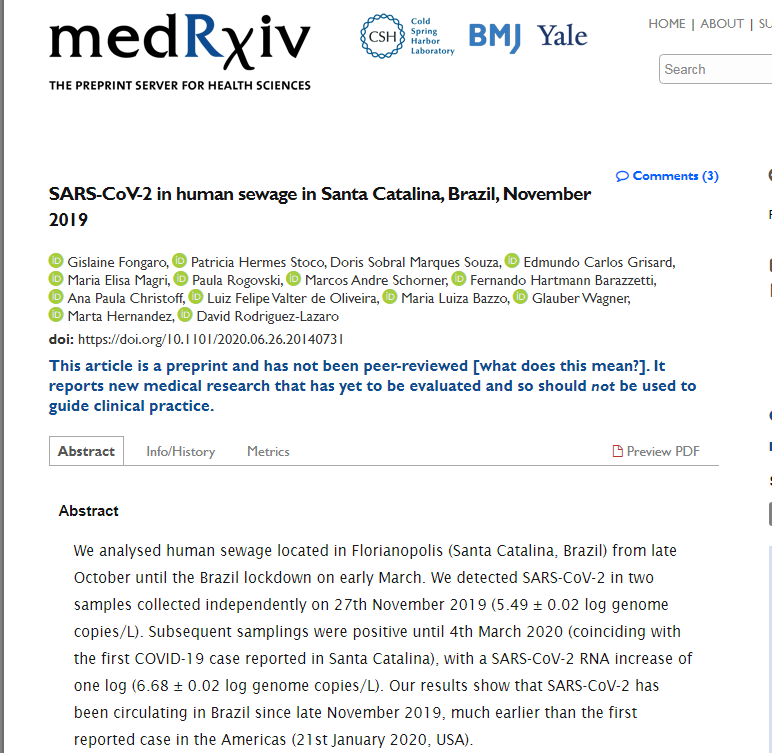

Screenshot of the study on medRxiv.

Screenshot of the study on medRxiv.

"We are sure of what we found in the November sample. It is the SARS-CoV-2 virus. We have no doubts about that," Patricia Stoco, a geneticist at the lab, told CGTN.

"We are now effectively working on sequencing the whole genome of these samples, so we'll be able to compare the sequencing of the virus found in our samples from late November with that of the virus now actually circulating and infecting people," she said.

"Doing that we could maybe detect mutations that could possibly explain the increase in the number of cases now," she added, stressing that comparing the full genetic sequencing is important to deepen understanding about the virus.

Gislaine Fongaro, a virologist at the university, explained how the research was conducted. She said the samples were collected from raw sewage in the pipes en route to the treatment plant.

"These samples were collected monthly between October 2019 and March 2020. So we take the samples to the laboratory and freeze them. That's why we could go back over them now – they were frozen," she said.

"Results came back negative for SARS-CoV-2 in the samples from October. And then negative again in the early November samples. But then results came back positive for the first time for a sample from November 27. And then all samples tested came back positive until March 2020," she explained.

She said it's possible that if they went further back, they could find more positive results for the novel coronavirus.

"It would be very important if we could review samples dating back to the beginning of the year [of 2019]," she said, adding that she hopes their research will encourage other teams who may have access to older samples to check them, and also encourage researchers to look into other older clinical samples taken from patients, which could also help tell the story of the virus.

"Because if we found this in the sewer, that's because people were already carrying the virus. That means there were already people who were infected but were not diagnosed because we did not know about the virus back then," she noted.