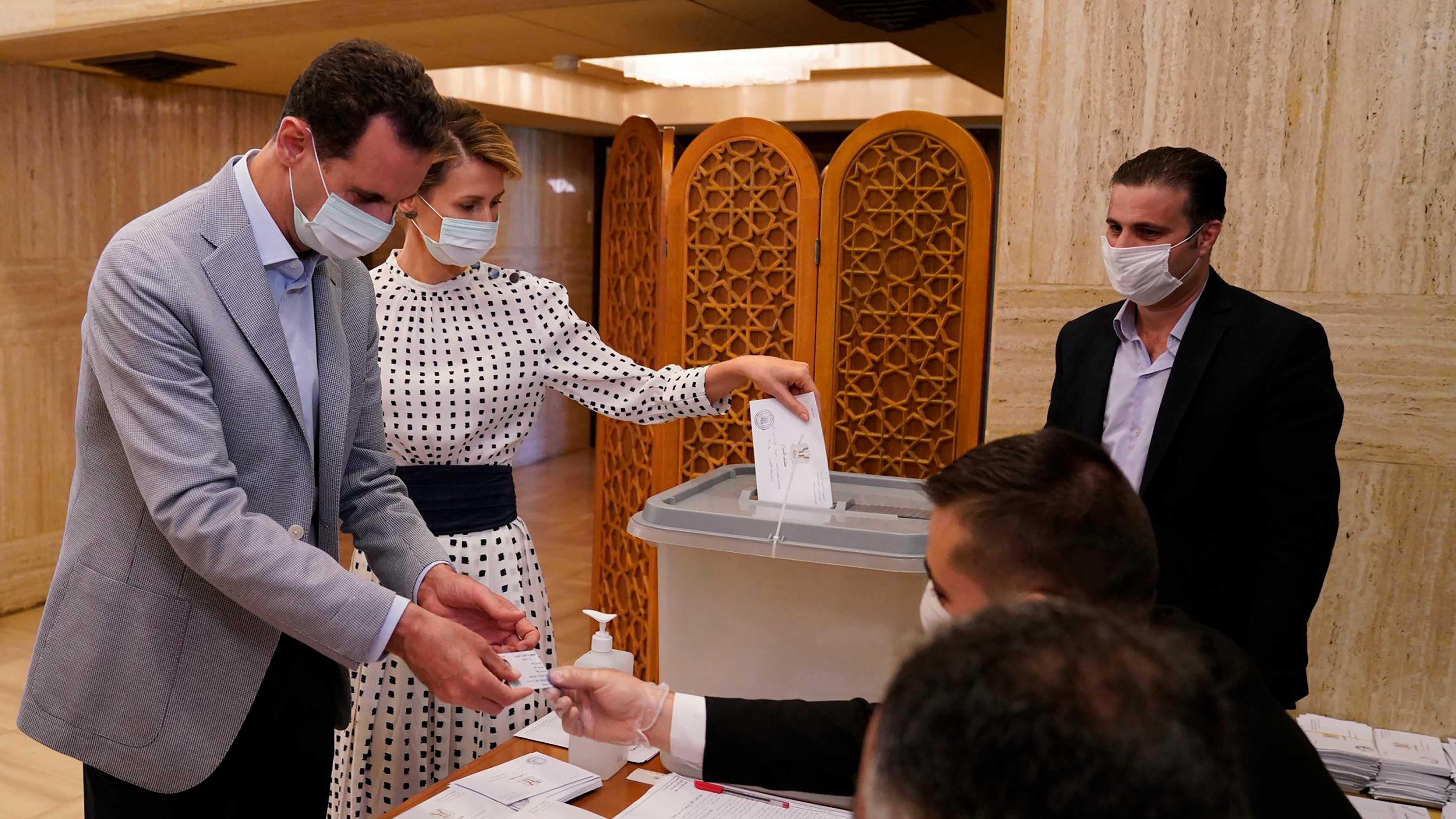

Syrian President Bashar Assad and his wife Asma vote at a polling station in the parliamentary elections in Damascus, Syria, July 19, 2020. /AP

Syrian President Bashar Assad and his wife Asma vote at a polling station in the parliamentary elections in Damascus, Syria, July 19, 2020. /AP

Editor's note: Guy Burton is an adjunct professor at Vesalius College, Brussels. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

After a slight delay, the results of July 19 parliamentary elections have been released in Syria. Of the 250 seats contested, President Bashir al-Assad's governing Baath party and it allies won 177 seats. Turnout was 33 percent, almost half what it was at the last election in 2016, when 57 percent of the electorate voted.

The victors and losers include famous and less famous names. A prominent parliamentarian, Fares Shehabi, failed to be elected in Aleppo and claimed that he was pressured to pull out. Another prominent figure and local warlord and businessman, Hossam Qaterji, who is subject to sanctions by the European Union, was re-elected.

In addition to these two, other, less well-known figures were elected. As the results came in, Syrian social media speculated why this was. One suggestion was that perhaps the government wanted to portray itself as more attentive to society's concerns. Another was that it would be easier to control and manage such figures.

The presence of less high-profile people in the parliament contrasted with the large number of militia leaders and local businesspeople who were standing for election. Their prominence reflects the changes that have taken place in Syrian politics and society over the past decade of war.

The election was the third that Syria has run for its parliament since the uprising in 2011 and subsequent war. It was postponed from its original date in April, initially because of concerns over the coronavirus. However, the government claims to have a grip of the crisis and may have seen the election as a way of illustrating that point. So far there have been around 500 cases in the territory which it currently controls. But that may well be an underestimate and mask a much larger caseload and problem.

The election also occurred at a time of transition for Syria. During the last elections in 2016, the government was in a more precarious position. At the time it was pushing back against various rebel groups, including the Islamic State, which was seeking to establish a caliphate in the east of the country. Six months earlier, Russia had intervened directly in the war, in a bid to bolster the regime.

Since then, the Syrian government has reclaimed much of its territory with military and financial assistance from its Russian and Iranian partners. But it still does not have complete control of the country. On July 19th, only 70 percent of the country was able to take part, with no polls taking place in opposition-held Idlib province or the autonomous Kurdish region in the north.

Despite this, Assad remains strong in the rest of his country and regardless of the criticism directed against him and corruption in his regime by Russian media earlier in the spring.

That media discontent may have reflected Russian frustration over the extent of their control over Assad and his political direction for Syria. They would like to see Syria rehabilitated internationally and feel that Assad is not moving fast enough on this.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad speaks during an interview with Russia Today in Damascus, Syria, March 5, 2020. /AP

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad speaks during an interview with Russia Today in Damascus, Syria, March 5, 2020. /AP

Opposition groups, Turkey and Washington have all questioned whether the election was meaningful, given that the government vetted all the candidates beforehand and overt opposition was unlikely.

Assad has brushed aside the criticism. He is confident that there is an alternative to him. In recent months he has asserted his control over the regime by moving against his cousin, Rami Makhlouf, a powerful economic figure in his own right. Before the war he was believed to control up to 60 percent of the Syrian economy. For any new business to succeed in the country requires his involvement and a commission, leading to his moniker, "Mr. Five Percent."

A consequence of the Assad-Makhlouf feud has been the exclusion of the Syrian Socialist National Party from the election. Although aligned with the regime, it is close to Makhlouf.

Economic issues were therefore a more prominent feature of candidates' messages during the election. In 2017 the World Bank calculated that along with half a million dead, half the population displaced and a third of homes completely or partially destroyed, the cost of reconstruction between 2010 and 2016 was 226 billion U.S. dollars – four times the country's GDP. A year later those estimates had gone up, the highest being put at 400 billion U.S. dollars.

Within this context, the past year has seen a substantial deterioration and signs that economic difficulties are reaching the elite. Many of those hoping to win a parliamentary seat learned that they would not be entitled to the usual economic benefits owing to austerity and sanctions.

For Syrians more generally, the cost of living has dramatically risen. Whereas the exchange rate was around 50 Syrian pounds to the U.S. dollar in 2011, by the end of 2019 it had risen to around 1000 pounds and 3000 pounds by June 2020.

An important contributing factor to this was the economic crisis engulfing Lebanon next door. In an effort to evade earlier sanctions and continue carrying out financial transactions, many better-off Syrians held deposits in Lebanese bank accounts, estimated between 14 and 30 billion U.S. dollars. In an attempt to prevent runs on its banks, Lebanon's government restricted the amount that could be taken out.

In addition, Syrians face a new complication through the Caesar Act, which came into law in the U.S. last month. Although it will have little impact on U.S.-Syrian trade, which was already limited, its effect may be international, especially as it allows for sanctions against foreign companies doing business in Syria. Among those concerned are the same Lebanese banks that are holding Syrian deposits, with many uncertain whether they will be targeted.

Regardless of the eventual election results, Assad's main priority this year will be acquiring much needed funds and investment to rebuild Syria. However, neither of its two main partners, Russia or Iran, are in a position to provide the amounts necessary for large-scale reconstruction while the West is unwilling to contribute without conditions, including constitutional reform and the inclusion of Assad's opponents in the political system.

As for some of the Gulf states, although there has been a diplomatic rapprochement in the past few years, they have so far been reluctant to commit any significant monies.

In the absence of other sources, both Assad and other Syrian officials have been keen to court China as a partner and investor.

The areas of mutual benefit that have been put forward include the possibility of developing the port at Tripoli on the Lebanese coast and linking it to Aleppo and Homs via Beirut, as a way to boost trade and provide an alternative to the Suez Canal.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)