Age will no longer be an excuse for children as young as 12 in China to get away with murder, as the country's top legislature considers lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) under certain circumstances and through special procedures.

Amid public outcry to punish underage killers in extreme cases, Chinese lawmakers have set in motion amendments to the country's criminal law during the five-day session of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People's Congress (NPC).

Under the current Chinese law, children aged 13 and under would not face criminal charges if they commit a serious crime, such as intentional homicide and rape.

The proposal has received overwhelming public support after several recent high-profile murders involving minors prompted widespread calls to bring the perpetrators to justice.

'Little devils'

In October 2019, a 10-year-old girl in Dalian, Liaoning in northeast China, went missing. She had been sexually assaulted, stabbed to death and dumped in the woods before her distraught parents found her bloodied body the next day.

Her killer was a 13-year-old schoolboy.

Addressed only as Cai, the boy received three years in a rehabilitation facility for the girl's murder because he was under the age of 14 – the MACR in China, when he committed the crime. The ruling outraged the nation and led to heated debate over the appropriate age for minors to be held accountable for serious offenses. Some pointed out that at the time of the crime, Cai was less than three months away from turning 14, the age that would result in a very different outcome.

A screenshot of the Dalian authorities' October 14, 2019 announcement about a 10-year-old girl's murder by a 13-year-old boy. /Weibo

A screenshot of the Dalian authorities' October 14, 2019 announcement about a 10-year-old girl's murder by a 13-year-old boy. /Weibo

As more details of the case emerged, media reports portrayed the youth as a callous and manipulative character mature beyond his age. This month, following reports that Cai's parents have been detained for failing to honor a court decision related to the 2019 case, the chilling details resurfaced again, spurring people to demand justice for the victim and her family.

Similarly, a 12-year-old boy in central China's Hunan confessed to stabbing his mother to death in 2018. Within days, he was released and sent back to school after prosecutors were unable to charge him with a crime. When confronted about his action, the boy reportedly said, "I didn't kill. It was only my mother."

In light of the disturbing incidents, a nationwide conversation about children who are capable of cruel acts – labeled "little devils" by the media – has been gaining momentum. This summer, a hit Chinese series "Hidden Corner," also known as "The Bad Kids," shone a light on the complexities of children's supposed "innocence" and brought the real-life horrors back into public consciousness.

An illustration with a less than 14 sign painted in red, suggesting that children under 14 are capable of violent crimes. /VCG

An illustration with a less than 14 sign painted in red, suggesting that children under 14 are capable of violent crimes. /VCG

The lowering of MACR inevitably raises questions about the lower limit and the rights of minors. "If we have eight-year-old killers, do we lower the age to eight? One day a seven-year-old kills someone, then what?" an internet user pondered in a comment on Weibo.

Official data from 2018 shows China's juvenile crime rates have been declining for nine consecutive years. But the majority of people on Chinese social media applaud the new proposed MACR, with some arguing that kids today "mature earlier" compared to previous generations, and laws reflecting the changed conditions are long overdue. Others say the practice of "malice supplies age" in some countries should be adopted when assessing juveniles' culpability.

Education over punishment – an ongoing debate

Globally, the MACR can range from as low as seven or eight to a more commonly accepted level of 14 or 16. The United Nations currently recommends 14 and considers a MACR below 12 not to be internationally acceptable.

According to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), the physical and psychological differences between children and adults constitute the basis for the lesser culpability of the former when in conflict with the law.

This is also the reason for a separate juvenile justice system, which seeks to educate rather than punish child offenders. In the best interests of the child, the traditional objectives of criminal justice "must give way to rehabilitation and restorative justice objectives," the UNCRC said.

While education is universally favored over punishment when it comes to child offenders, whether rehabilitation can successfully reintegrate them into society leaves much room for debate.

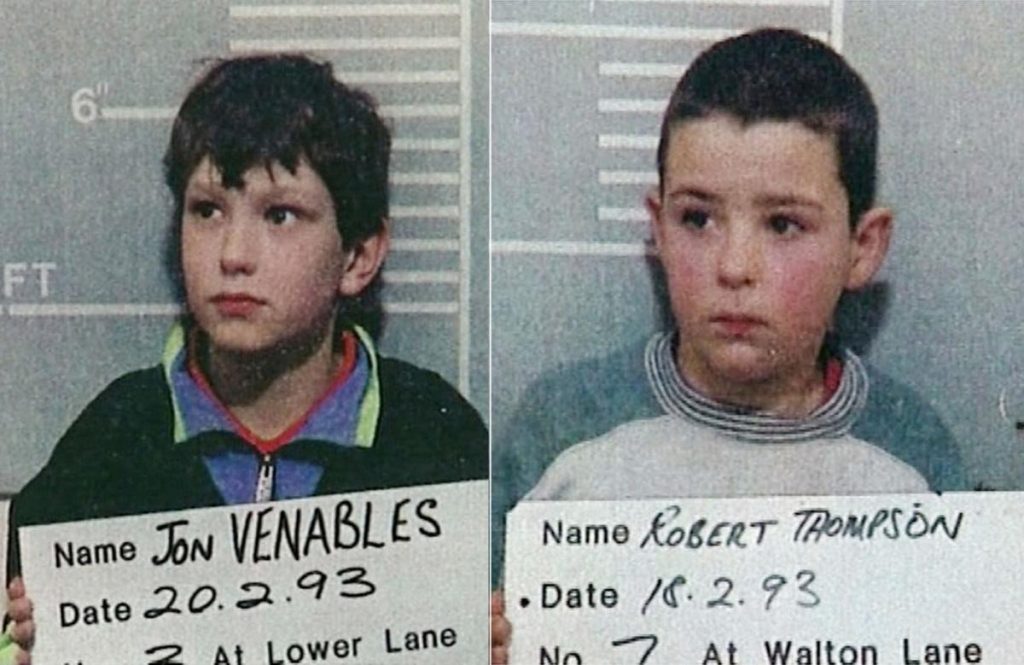

In a 1993 murder that horrified Britain, two 10-year-old boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson, became the youngest convicted murderers in the country in 250 years for kidnapping, torturing and killing a two-year-old toddler, who they then left on a railway track to be mutilated by a passing train.

The judge presiding over the trial described the boys' act as "unparalleled evil and barbarity," while hundreds of angry protesters demanded "hanging" for the two outside the courthouse. They were released in 2001 after serving a reduced sentence due to their age.

But in 2018, at age 35, Venables was jailed again for a child pornography offense, the second such transgression by the notorious man since his 2001 release. However, his accomplice in the 1993 murder, Thompson, has so far not been known to have come into contact with the law again.

Venables and Thompson were convicted of murder in 1993 at age 10. /AP

Venables and Thompson were convicted of murder in 1993 at age 10. /AP

The exact cause behind a failed attempt to rehabilitate a child criminal may remain a mystery, just like what goes on inside a serial killer's mind. It could be any combination of bad parenting, environment, mental health or even innate evil.

Experts in China largely support establishing an improved and tailored rehabilitation system, which the new amendments have sought to address. "Minors will not get death penalty in China no matter what serious crimes they commit, so eventually they will return to society," Xi Peizhi from the Shanghai Society for Juvenile Delinquency Prevention Research told the Shanghai Law Journal. "From a rational point of view, specially designed correction measures will work better than jail."

But others believe the point of criminal justice remains to punish, which should not be completely overridden by the need to educate. "Education is an added value that comes with the punishment," wrote Xu Wenhai, assistant professor at Tongji University Law School, in an op-ed on October 13.

"When they commit the crime, at that moment, all these years of education they receive, from school or from family, only goes to show how little of an effect it has on them," Xu said. "Then they need a different kind of education. It is called punishment."