Hours before the Paris Agreement came to fruition, there were still doubts if it was going to happen.

After all, too many things could go wrong in any treaty that involves 196 countries, especially with the failure of the last conference held in Copenhagen fresh on the mind. Even tiny nuances in wording could send the decades-long negotiations back to the drawing table, again.

The grueling process that led up to the landmark climate deal was often compared to running a marathon. For two weeks, diplomats huddled in the town of Le Bourget on the outskirts of Paris, holding hotel room meetings late into the night while scanning details as small as a punctuation mark within the mountains of documents.

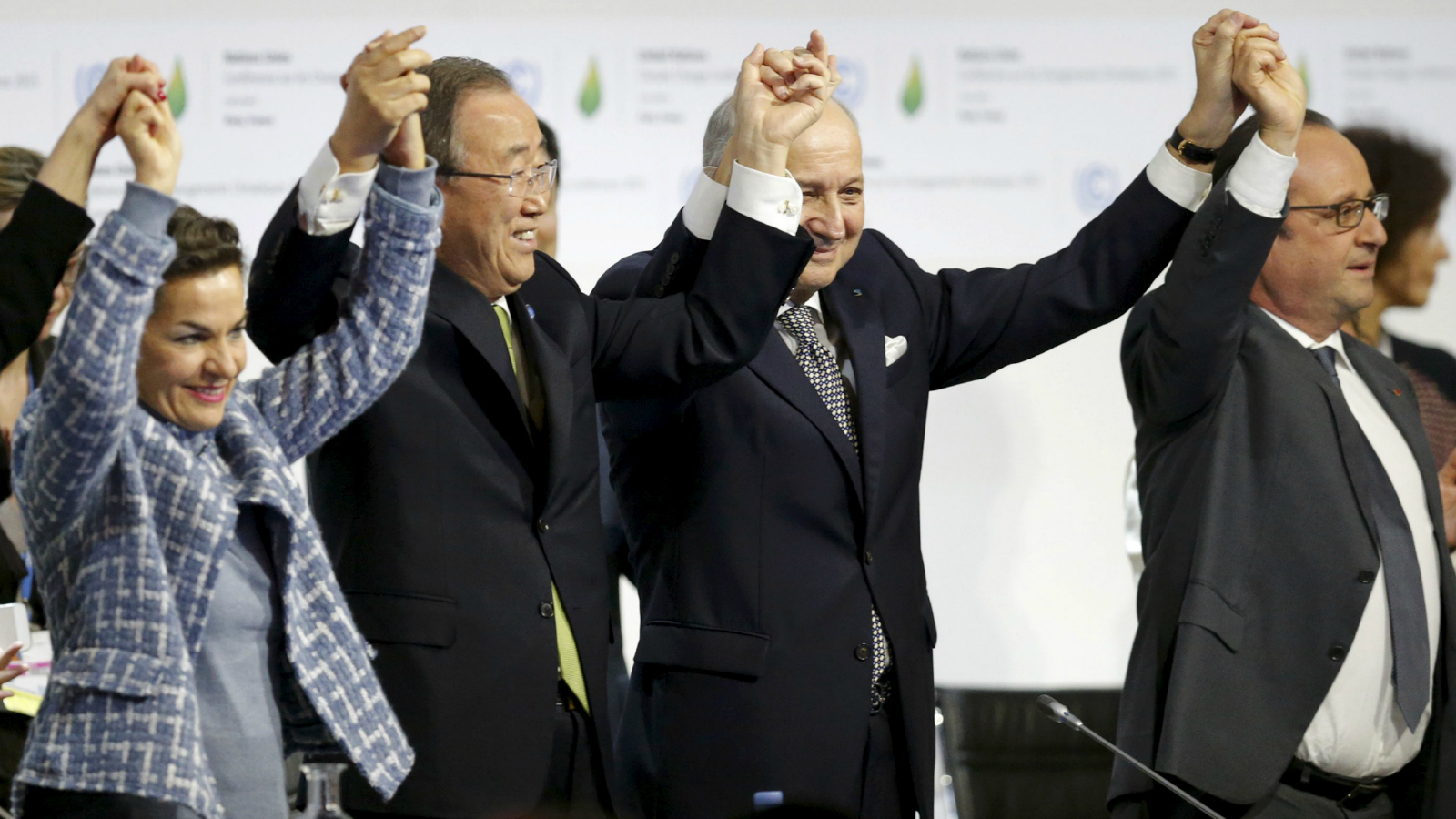

The exhausting days and nights culminated on Saturday, five years ago, when French foreign minister Laurent Fabius finally appeared on stage after a two-hour delay and banged down the small green-topped gavel that signified global cooperation – the deal that involved every nation on Earth was approved.

In the most ambitious climate deal in history, all countries are required to limit greenhouse gas emissions in order to achieve the overarching goal of bringing global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and constraining temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

If the 2-degree-Celsius threshold is breached, argued the world's top scientists, a series of natural disasters such as the sea-level rise and prolonged flood and drought would set the world on an irreversible course to climate catastrophe and lead to some 1.2 billion people being displaced by 2050, according to a recent analysis by the Institute for Economics and Peace.

06:42

Diverged paths

After the deal was reached, China and the United States – the world's biggest and second-biggest polluters – have taken drastically different paths in responding to the threat of climate change.

Riding on a wave of populism, U.S. President Donald Trump repeatedly cast doubt on global warming, calling it an "expensive bullshit" and a "hoax" created by the Chinese to "make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive." After rolling back nearly 100 environmental initiatives enacted under his predecessor Barack Obama, Trump ultimately fulfilled his campaign promise of withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Agreement earlier last month.

"The Paris Agreement handicaps the United States economy in order to win praise from the very foreign capitals and global activists that have long sought to gain wealth at our country's expense," Trump stated after the decision. "They don't put America first. I do, and I always will."

Trump's brazen cynicism in the face of a pending global crisis was criticized by world leaders, including U.S. allies such as France and Canada. Nonetheless, U.S. emissions somewhat decreased "because the forces of the market and businesses are going in the opposite direction," said Erik Solheim, former UN Environment Executive Director, during an interview with CGTN. "Big U.S. companies are far ahead of politics."

Meanwhile, China and other nations have stepped up their effort in developing renewable energy and reduced their reliance on fossil fuels, from government policies to market forces. China's forest area has expanded fast for the past decade, leading the world in forest growth. The country has also contributed massively in clean R&D, reaching $6.3 billion – the first among all member states. Half of the world's solar panels are sourced from China, according to Solheim, also former UN under-secretary-general.

The European Union (EU), the planet's third-largest emitter, provided the most public climate fund to developing nations, and in the meantime spent 20 percent of its budget on curbing global warming between 2014 and 2020.

In the southern hemisphere, Australia has been developing the fuel of the future that won't produce any CO2 – hydrogen.

"Five years on, it's clear the Paris Agreement is driving climate action," said Professor Niklas Höhne of NewClimate Institute. "Not only is our warming projection for government climate pledges falling to just over two degrees, a level that puts the Paris Agreement 1.5 Celsius target within reach, but we're also seeing a drop in projects for real world action."

In the absence of the U.S., the EU, China, India, and several other large emitters launched the International Platform on Sustainable Finance to mobilize private investment into environmental sustainability.

Adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, Paris, France. /Reuters

Adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, Paris, France. /Reuters

Looking to work in unison

Fighting climate change is a long-haul one, requiring effort from all parties involved – governments, businesses, academics, and the public. According to data from the Climate Action Tracker in December 2020, "2.9 is the median of the low and high ends of current policy projections." The slight fall from 3.6 degrees Celsius, it predicted five years ago, could partly be attributed to the historic climate agreement.

But the world could have done more. If countries had taken action a decade ago, they would have needed to cut emissions by 3.3 percent every year, according to the 2019 emissions gap report released by the UN Environment Program. Now they have to meet an annual reduction of 7.6 percent till 2030, a threshold most countries find out of reach with their current climate action plans.

"Now we are at the moment in history when all the forces are going at the same time in the right direction," Solheim noted. "But the speed is too slow."

One of the major obstacles came from the absence of the world's biggest historical emitter and second-largest emitter currently. But with a Joe Biden presidency approaching, climate cooperation among major polluters is set for a seismic shift. Biden appointed John Kerry – the key U.S. official in shaping the Paris climate accord – the U.S.'s first climate envoy, expected to take the country out of the climate change limbo by facilitating a transition away from coal, oil, and natural gas toward renewable energy. "Five years ago today, the world gathered to adopt the Paris Agreement on climate change. And in 39 days, the United States is going to rejoin it," Biden tweeted on Saturday.

Read more: Climate cooperation could signify return to China-U.S. diplomacy

Across the pond, China has committed to leveling off carbon emissions no later than 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2060. "China will scale up its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions by adopting more vigorous policies and measures," said Chinese President Xi Jinping, who called for a "green revolution" during the 75th session of United Nations General Assembly held in September. He reiterated on Saturday some commitments for 2030, including lowering CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by over 65 percent from the 2005 level, and increasing the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25 percent.

Read more: Full text: Xi Jinping's speech at Climate Ambition Summit 2020

"By the term 'green revolution,' it means we have to undergo a revolution of not just production mode but also lifestyle," Fang Li, China director of the World Resources Institute, told CGTN. Consumers are both contributors and victims to emissions and hence must be involved in this "revolution." Her institute estimates that the water used to produce food that has been wasted could sustain Beijing for eight years.

"The declaration made by Xi that China will go carbon neutral by 2060 sent shockwaves into the entire global environmental system," Solheim said. Japan and South Korea, which heavily rely on fossil fuels, followed up to make carbon-neutral pledge by 2050.

India – the fourth largest emitter – intends to cut emissions intensity by 33 to 35 percent below 2005 levels, along with generating 40 percent of electricity from non-fossil-fuel resources by 2030.

"It's widely anticipated that China, the U.S., the EU, and other member states can sit at the table and look for feasible solutions in the next few years," Fang added. Both she and Solheim agree that constructive competition will probably dominate future climate actions. "There's nothing bad if we have a green competition on the verge of irreversible climate change," said Solheim.

(Video editor: Chen Shi)