Reporting has never been tougher in my eight years of working as a journalist. Since international relations constitute a large portion of my reporting, simmering geopolitical tensions between China and the U.S. as well as the wider Western world is making it harder to get genuine interviews.

Though writing about bilateral relations has become second nature to me, I find myself clueless in front of conflicting information and news taking sharp turns.

Back in the spring of 2018, I had never imagined that the trade war would be the start of an escalating brouhaha over the economy, hi-tech, military superiority and even human rights. All these amount to ideological competition, many experts of American studies said during interviews, often to their great dismay.

Even though quite a few politicians and academics feared the start of a Cold War 2.0 between the two juggernauts, I could still get interviews from various angles, though doing so had cost me more time and energy. But day by day, the rhetoric has become daggers drawn, while the rivalry has overtly become a clash of values. If China-U.S. ties could be described as topsy-turvy in 2018 and 2019, it's fair to say that they've been in a downward spiral over the past year in light of the disruptive blame game over the pandemic.

The press is rife with one-sided stories, hugely affected by their own interests and also catering to a public sentiment colored by nationalism and populism. Seeking the truth and then presenting it objectively amid the roller coaster of the China-U.S. heat-up is an unnerving process.

Sources of tensions are increasingly manifold. The just-concluded Alaska meeting – the first high-level face-to-face between China and the U.S. during the Joe Biden administration – went awry shortly into the opening session. The EU soon after announced sanctions against China over "severe human rights abuses in Xinjiang," the first of its kind in 30 years. In the latest whirlwind, cotton has become the focal point in the geopolitical sparring, with several clothing retailers facing boycotts by Chinese consumers after a ban on Xinjiang cotton.

It seems the divide between Beijing and Washington continues to grow, bandying words blatantly while diplomatic demeanor has absconded.

Wall Street no longer lobbies Washington for closer economic ties with China. /Reuters

Wall Street no longer lobbies Washington for closer economic ties with China. /Reuters

While there's little good news in bilateral ties, I can feel the aspiration from people of conscience committed to reviewing policies of both sides to repair the bruised relationship. However, at a time when anti-China policy is consensus among the U.S. bipartisan elite and when Wall Street no longer lobbies Washington for closer economic ties with China, there's not much left that they can do.

"I think we should focus first on areas where we can feel our common humanity," said Tim Stratford, former U.S. trade representative for China affairs, on the sidelines of a cultural event recently held by the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) in Beijing. Before this talk, I had interviewed him twice, both on tough issues including the tariff war and the strife on technology and intellectual property. Each time the scope of interview topics for him expanded from trade only to a range of bones of contention.

Read more:

AmCham chief: China, U.S. have to deal with each other

Ex-AmCham chairman: China, U.S. must live in same world despite disagreement

Stratford has lived and worked in China since 1982 and served multiple roles in facilitating American business operations and developing U.S. trade policies toward China. The former chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in China suggested both sides move more slowly and make sure not to break things. "As we look at the great achievements in bilateral relations since Kissinger's visit 50 years ago, I think we should not throw away those positive things so quickly."

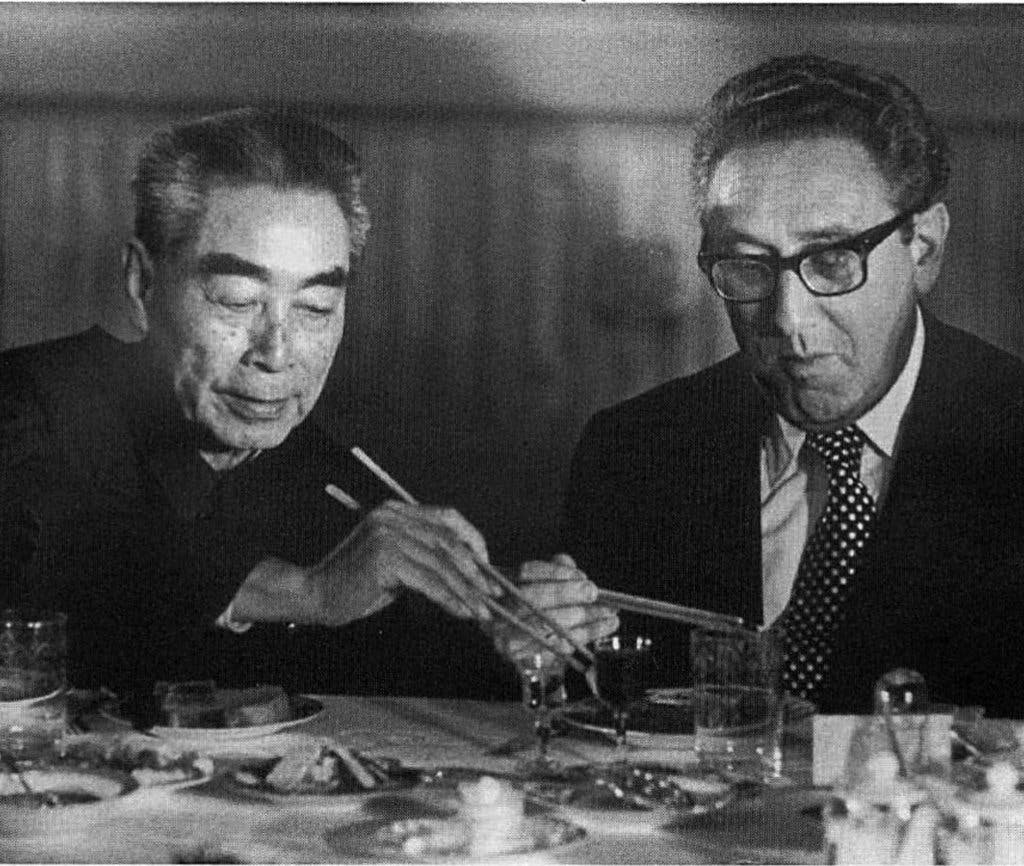

Zhou Enlai (L) and Henry Kissinger in Beijing, 1971. /Henry Kissinger Archives

Zhou Enlai (L) and Henry Kissinger in Beijing, 1971. /Henry Kissinger Archives

Speaking at a Chatham House event on Friday, Henry Kissinger warned of a grave conflict if the U.S. and its Western allies fail to reach a new understanding with China, which will soon be more advanced in some areas.

"If we don't get to that point and if we don't get to an understanding with China on that point then we will be in a pre-World War One-type situation in Europe, in which there are perennial conflicts that get solved on an immediate basis but one of them gets out of control at some point," the 97-year-old diplomat said.

Humanity constitutes a universal foundation that leads up to understanding among human beings. It's something beyond nation and race, economy and politics.

"If you add the human element to the beauty of art, it's a very powerful way for people to feel the common humanity," Stratford said. The veteran trade official who's overseen a spectrum of bilateral events is reminded of ping-pong diplomacy which helped thaw the Cold War ice back in the 1970s.

Like Stratford, many in the auditorium are nostalgic of this historical engagement. Zhao Bin, senior vice president of U.S. chip tycoon Qualcomm, is one of them.

"China-U.S. relations started from the ping-pong diplomacy. But nowadays the world has changed … Kungfu could become a new kind of mediation mechanism to help ease the tensions between the U.S. and China." He talked excitedly about a documentary on Kungfu diplomacy made by Laurence Brahm, an activist and filmmaker dedicated to bridging the gap between China and the Western world.

I'd seen Zhao on various occasions over the past couple of years but never got the chance to sit and talk to him. He'd always been on a hectic schedule on one hand, and semiconductor chips is a highly sensitive issue given the tangle with Huawei, on the other.

The veteran lawyer, once a graduate from the department of Chinese language and literature of Peking University, believes in the power of art and culture to solve the real problems, just like Tian Haojiang. Tian, 65, is the founder and artistic director of iSING! International Young Artists Festival, a program that brings singers from the U.S. to China to help them sing opera in Chinese.

04:39

"It's now a very difficult period for the relationship between China and the U.S. But I believe you have to keep working in what you believe in," said Tian, who went to the U.S. in the early 1980s and has started singing at the Metropolitan Opera since 1991. He told the story of an American soprano who had been in the music program for three straight years, noting that she just wanted to sing in China.

These cultural events, moreover, highlight the similarities between cultures rather than what divides them. "Recently when you look at the international scenario, there's a lot of emphasis on what's separating people, on the differences among countries, which are completely natural," observed Tatiana Lacerda Prazeres, now a senior fellow at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing and non-resident senior fellow of the CCG.

"But at the same time, sometimes we need to take a break, take a breath, and realize we, as human beings, share a lot in common, common values." The former senior advisor to the WTO director-general and former foreign trade secretary of Brazil believes art and culture connect people and hence underpin political and economic links between countries.

When trade meets rising barriers, protectionism and unilateralism, the cultural event is vital to clearing away the miasma while reminding people that the two countries across the Pacific have shared values.

In the modern globalized world, there is little chance of a second Cold War happening between the two powers because there are so many areas of cooperation. Yet for the political and thought leaders in either country, finding common values and interests only serves to start the conversation at the highest levels. Without support from the public, communication would cease and people would only be taking at each other.

What would truly strengthen bilateral ties is for Chinese and Americans to find commonalities at the grassroots levels, where ignorance can drive prejudice. A lot of work still needs to be done at all levels, so I hope my reporting in the future can reflect the fruits of such efforts.

(Video made by Qi Jianqiang)