Representative image: The mine countermeasures ship USS Patriot (MCM 7) sails with JS Enoshima (MSC-604) during Mine Warfare Exercise (MIWEX) 2JA 2020 in Mutsu Bay, Japan, July 21, 2020. /U.S. Navy Photo

Representative image: The mine countermeasures ship USS Patriot (MCM 7) sails with JS Enoshima (MSC-604) during Mine Warfare Exercise (MIWEX) 2JA 2020 in Mutsu Bay, Japan, July 21, 2020. /U.S. Navy Photo

Editor's note: Abhishek G Bhaya is an International Editor with CGTN Digital. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Last week, the U.S. Navy carried out a freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) in India's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the western Indian Ocean without prior permission, sparking an outrage in New Delhi which saw the operation as a blatant disregard of its domestic as well as international maritime laws.

The incident also revealed an obvious rift between two members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, in their perception of "freedom of navigation" and "rules-based order" that the bloc claims to defend under a nebulous Indo-Pacific strategy.

While it was not the first time that the U.S. Navy transgressed into India's fishing waters, what rattled the mandarins in New Delhi more was a public statement issued by the 7th Fleet of the U.S. Navy asserting its action against "India's excessive maritime claims" in a language that didn't appear coming from a "friendly" Quad ally.

As screenshot of the statement released by U.S. 7th Fleet Public Affairs. /U.S. Navy

As screenshot of the statement released by U.S. 7th Fleet Public Affairs. /U.S. Navy

The U.S. statement asserted that India's requirement of prior consent for military exercises or maneuvers in its EEZ or continental shelf was "inconsistent with international law."

India claimed otherwise. In a statement released by Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), it reminded the U.S. that the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) doesn't allow for foreign military exercises or maneuvers in the EEZs of a coastal state.

The MEA statement, that came two days after the incident following much uproar in the strategic circles in New Delhi, said that India's concerned were conveyed to the U.S. through diplomatic channels.

A screenshot of the statement released by India's Ministry of External Affairs. /Government of India

A screenshot of the statement released by India's Ministry of External Affairs. /Government of India

Hint of racism and imperialism

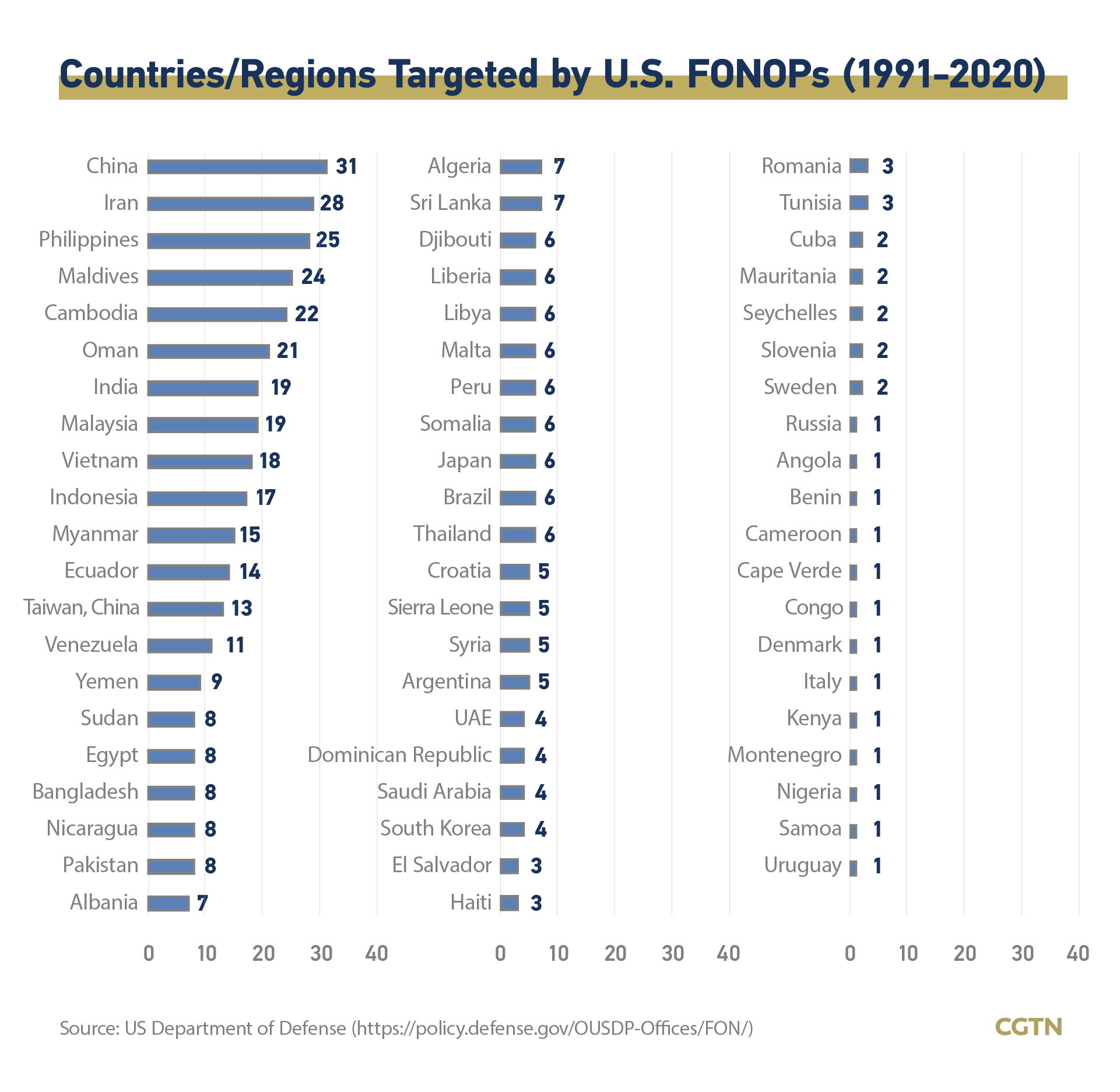

The U.S. Navy has been carrying out FONOPs since 1991, and has repeatedly asserted that these operations are conducted against both friends and foes without discrimination. However, a quick glance of the annual FONOP reports released by the U.S. Department of Defense for each fiscal year, makes it evident that a vast majority of these military operations are targeted at Asian and non-Western countries.

It is not surprising that China and Iran are the top two targets of such missions, attracting a total of 31 and 28 FONOPs. In recent years, the U.S. has carried out FONOPs against China with increased frequency and brazenness. In the past two years alone, it conducted as many as 14 such exercises in the Chinese EEZs in South China Sea and East China Sea. This is a constant source of provocation for Beijing and also among the primary causes of heightened China-U.S. tensions.

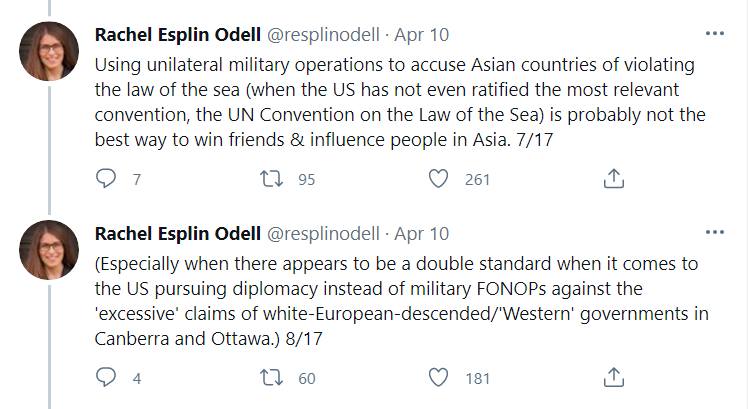

"First, though the U.S. does conduct FONOPs against not only rivals but also allies & partners, it still picks & chooses. Most notably, the U.S. has never conducted formal Freedom of Navigation operations against Australia or Canada, despite objecting to their 'excessive' claims," American analyst Rachel Esplin Odell said in a Twitter thread exposing the U.S. double standards on the issue.

Read also: Let's talk about the slavery that still exists in U.S. cotton 'prison farms'

"Though not against Australia & Canada, the U.S. has indeed conducted FONOPs against most other countries in the Indian & Pacific oceans that make what the U.S. govt deems to be 'excessive' maritime claims," said Odell, a research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

Another glaring irony is that the U.S. hasn't yet ratified UNCLOS, and yet it is most zealous in demanding that other states comply by its own interpretation of the maritime law. In contrast, China and India were among the first nations to sign the UNCLOS in December 1982 and subsequently ratify it in June 1996 and June 1995 respectively, within two years of the international law coming into force in November 1994. The U.S. only signed in July 1994.

"Using unilateral military operations to accuse Asian countries of violating the law of the sea (when the US has not even ratified the most relevant convention, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea) is probably not the best way to win friends & influence people in Asia," Odell reasoned.

A screenshot of couple of tweets from Rachel Esplin Odell. /Twitter via @resplinodell

A screenshot of couple of tweets from Rachel Esplin Odell. /Twitter via @resplinodell

Read also: US police officer who pepper-sprayed Black-Hispanic lieutenant fired

"Especially when there appears to be a double standard when it comes to the U.S. pursuing diplomacy instead of military FONOPs against the 'excessive' claims of white-European-descended/'Western' governments in Canberra and Ottawa," the American analyst added hinting at a racist and even imperialist undertone to these military operations.

Odell advocated that the U.S. should adopt a less militarized approach toward freedom of navigation instead of using its military might to impose its version of the so-called "liberal rules-based international order" on a world of "mostly formerly colonized nations."

"Indeed, the very fact the US deems as 'excessive' the maritime claims of such a broad swath of states in Asia suggests that perhaps we would do well to adopt a more compromise-oriented approach that does not deliberately disregard the security concerns of littoral states, especially non-Western formerly colonized nations, who have legitimate reason to fear foreign naval power given the history of its use in their subjugation," she added, defending the concerns of coastal countries that have protested U.S. FONOPs.

Ambiguous law, divergent views

The divergent views on "freedom of navigation" stem from the varying interpretations of the relevant UNCLOS sections by several coastal states and a few maritime powers, particularly the U.S.

Since the conclusion of UNCLOS in 1982, the general concept of an EEZ and the right for a coastal state to exercise sovereign rights over economic activity and resources have become customary international law. Experts however point out that as a relatively new concept in international law, the specific scope of rights and responsibilities in the EEZ is dynamic and ever-evolving.

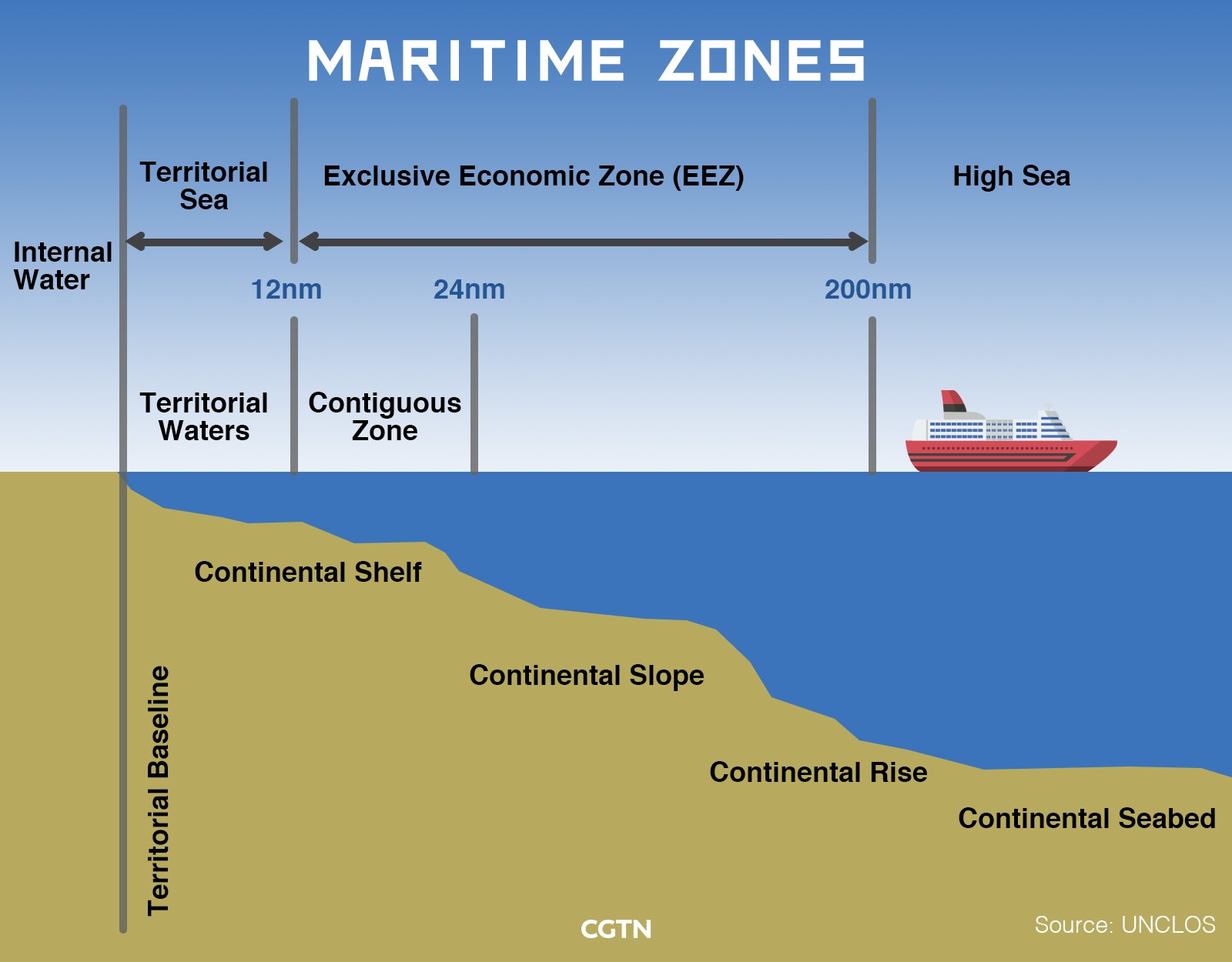

UNCLOS sets the width of the territorial sea at 12 nautical miles, with a contiguous zone at 24 nautical miles from the baseline; and establishes EEZs extending to 200 nautical miles from baselines.

However, the UNCLOS does not clarify the specific issue of military activities in the EEZ and a major source of contention continues to be whether maritime states may unilaterally conduct certain military operations in the EEZ of the coastal state without permission, states a 2012 research paper, authored by Jing Geng, currently a PhD researcher in international law at Catolica Global School of Law in the Portuguese capital Lisbon.

"Some maritime powers support unfettered military activity in the EEZ by emphasizing the freedom of navigation. Conversely, some coastal states object to military activity in their EEZ by expressing concern for their national security and their resource sovereignty," Jing noted in the paper that takes a close look at the legality of foreign military activities in the EEZ under UNCLOS.

China, India concur on EEZs

China and India are among the countries that seek greater control over foreign military activities in their EEZs. While ratifying UNCLOS, both the Asian countries had declared that in their understanding the treaty did not authorize foreign states to conduct military exercises in EEZ without prior permission. China and India have also passed domestic laws to back this perception, which is precisely what the U.S. FONOPs continue to challenge.

"This divergence in perspective regarding the legality of foreign military activities in the EEZ is partly due to varying interpretations of Article 58, which permits maritime states to engage in 'other internationally lawful uses of the sea related to these freedoms, such as those associated with the operation of ships, aircraft and submarine cables and pipelines, and compatible with the other provisions of this convention'," explained Jing.

"Thus, nations such as the U.S. perceive this provision to permit naval operations in the EEZ as an activity 'associated with the operation of ships' and more generally, as protected within the scope of the freedom of navigation," she added.

Who made U.S. the 'global-cop'?

The guided-missile destroyer USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) transits the Arabian Gulf, Oct. 27, 2020. /U.S. Navy Photo

The guided-missile destroyer USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) transits the Arabian Gulf, Oct. 27, 2020. /U.S. Navy Photo

It could be surmised that the U.S. conveniently uses this ambiguity in the UNCLOS to carry out FONOPs as part of a strategic plan to not only define international maritime laws as per its own convenience, but also to perpetuate its maritime dominance.

"There is rich irony in the fact that amongst the 168 nations who have either acceded to or ratified UNCLOS 1982, the US is conspicuous by its absence. The UN Secretariat has not charged any country with the role of overseeing or enforcing the implementation of UNCLOS. It is, therefore, intriguing to see that the U.S. has arrogated to itself a 'global-cop' role in its implementation," former Indian Navy chief, Admiral Arun Prakash opined in a piece published by The Indian Express.

Describing the 7th Fleet's latest FONOP in India's EEZ as "an act of impropriety," Prakash contended that "the time has, perhaps, come for signatories of UNCLOS 1982 to convene another conference to review laws and resolve issues of contention."

As a power that commands arguably the largest and the most sophisticated blue water navy, the U.S. continues to disregard the legitimate concerns of other coastal states that are born out of their fears of exploitation from a colonial past.

"At the end of the day, international law is about might being right. What the U.S. does as FONOPs, only the U.S. can do," Manoj Joshi, a distinguished fellow at New Delhi-based thinktank Observer Research Foundation told The Hindu newspaper.

Repercussions for Quad

Joshi admitted that last week's incident brought to the fore the "huge differences" on how the two Quad partners perceive "freedom of navigation" and a "rules-based order" in the Indo-Pacific region.

"I presume when you say rules-based order, you're talking about UNCLOS. I can't see on what basis the Quad can implement UNCLOS. Do we do it on the U.S. based understanding or Indian understanding? There are huge differences," he said.

India is also worried that U.S. FONOPs, if not challenged, could give way to a likely future scenario for other foreign navies to attempt similar maneuvers in its fishing waters. "Perhaps, UNCLOS itself needs revisiting," Joshi remarked, concurring with Admiral Prakash

In the light of these differences, India may increasingly find it untenable to support the Quad's proclamations of "freedom of navigation" and "rules-based order" in totality, impeding the strategic objective of the four-nation bloc, which many observers believe is a front to contain China.

It is also expected that Indian policymakers henceforth may possibly have a better appreciation of China's identical objections to U.S. FONOPs.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)