A screenshot from "Angola for Life: Rehabilitation and Reform Inside the Louisiana State Penitentiary" a 2015 documentary on the "plantation slavery" at Louisiana State Penitentiary, Louisiana, U.S., produced by The Atlantic. /The Atlantic

A screenshot from "Angola for Life: Rehabilitation and Reform Inside the Louisiana State Penitentiary" a 2015 documentary on the "plantation slavery" at Louisiana State Penitentiary, Louisiana, U.S., produced by The Atlantic. /The Atlantic

Editor's note: Abhishek G Bhaya is an International Editor with CGTN Digital. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

"You don't see the world as it is, you see it according to who you are.”

This saying by American educator Stephen Covey sums up the twisted allegations of "forced labor" with which the U.S. is trying to implicate the cotton industry in China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

As Washington and its allies along with the Western media push an aggressive propaganda campaign against the alleged "human rights" violations in Xinjiang without offering any credible evidence, one needs to take a closer look at the murky history of "forced labor" and "plantation slavery" in the U.S. cotton industry, which some say still continue, albeit under a political and legal camouflage.

"There's a lot of hypocrisy involved with the manufacturing of cotton in the United States. While slavery is legally banned in the U.S., the practice continues in the form of prison labor for convicted felons," China-based American expat Robert Vannrox told CGTN Digital, asserting that prison labor continues to be used in cotton farming in the U.S.

"Slavery is alive and kicking in the United States. Just that you don't call it slavery anymore," said Vannrox, who has previously worked with the U.S. government and military.

Many may find these claims bewildering but Vannrox is factually correct. The U.S. is perpetuating slavery, by all accounts, under the garb of prison labor. A dark chapter that is widely, and perhaps deliberately, overlooked by the West but needs reminding every time they take a moral high ground on the subject.

Slavery is legally banned in the U.S. but the practice continues in the form of prison labor for convicted felons. /Getty

Slavery is legally banned in the U.S. but the practice continues in the form of prison labor for convicted felons. /Getty

Watch and read: Is the West's Xinjiang campaign driven by U.S. plans to derail BRI?

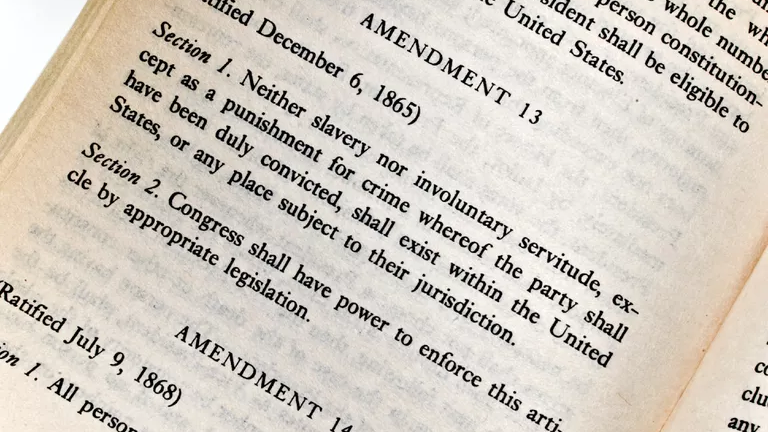

While it is widely known that the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865 abolished slavery, not many seem to grasp a crucial legal exception. Section 1 of the Amendment provides: "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Beyond the legalese, this simply means: Imprisoned felons have no constitutional rights in the U.S.; and they can be forced to work as punishment for their crimes. Slavery from the back door, if you will.

The discriminatory legal and judicial system in the U.S. has ensured that a large number of African American men are declared felons and therefore eligible for prison labor, which is just another form of slavery. "In the United States, if you're a Black person, chances of your becoming a felon is very high. One third of Black men in America are felons," said Vannrox.

A 2017 report by Population Association of America substantiates Vannrox's claims. "We estimate that 3% of the total U.S. adult population and 15% of the African American adult male population has ever been to prison; people with felony convictions account for 8% of all adults and 33% of the African American adult male population," the report stated.

'Cotton production prisons'

According to Vannrox many of the cotton farms in the U.S. are run by prison laborers under harsh conditions, which is a modern version of slavery. "In Arkansas, they have set up prisons where they actually farm cotton. The funny thing and the hypocrisy that is involved is that many of these prisons are former slave plantations," he said.

The Cummins Unit is one of the biggest cotton production prisons in Arkansas. /Wiki Commons

The Cummins Unit is one of the biggest cotton production prisons in Arkansas. /Wiki Commons

Read also: China backs Xinjiang firms, residents in lawsuits against Adrian Zenz

"The biggest cotton production prisons in Arkansas are Cummins Unit (Lincoln County) and the East Arkansas Regional Unit (Brickeys)," Vannrox noted.

The Cummins Unit with a capacity of 1,725 is one of the largest prisons in Arkansas. The prison farm (formerly known as the Cummins State Farm) is built in an area of 16,500 acres (6,700 hectares) and occupies the former Cummins and Maple Grove plantations. Cotton is among the chief cash crops, along with rice and corn, that the prisoners harvest in the facility.

The U.S. is the third largest cotton-producing country behind India and China. Texas, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas are the major cotton producing U.S. states. Vannrox maintained that most of the cotton in the U.S. comes from the American prison system funded by the U.S. government.

An archived New York Times report from June 16, 1964 about two New York State prisons receiving "subsidies under the Government's new cotton program" establishes a direct link between prison labor and cotton plantation, which Vannrox insisted continues even today.

A screenshot of The New York Times archived report from June 1964 about two New York State prisons receiving subsidies under the government's new cotton program. /The New York Times

A screenshot of The New York Times archived report from June 1964 about two New York State prisons receiving subsidies under the government's new cotton program. /The New York Times

'Slavery reinvented in Angola prison'

As recently as 2015, American media platform The Atlantic in its documentary "Angola for Life: Rehabilitation and Reform Inside the Louisiana State Penitentiary," portrayed a rather murky scenario at the country's largest southern slave-plantation-turned-prison.

The facility is named "Angola" after the African country that was the origin of many slaves brought to Louisiana. It is also popularly known as "The Farm" and "The Alcatraz of the South."

"Crops stretch to the horizon. Black bodies pepper the landscape, hunched over as they work the fields. Officers on horseback, armed, oversee the workers," The Atlantic wrote describing the first scenes from its documentary in a report.

"To the untrained eye, the scenes from the documentary could have been shot 150 years ago. The imagery haunts, and the stench of slavery and racial oppression lingers through the 13 minutes of footage."

The documentary raised disquieting questions about America's "subhuman" treatment of its prisoners. "Those troubling opening scenes of the documentary offer visual proof of a truth that America has worked hard to ignore: In a sense, slavery never ended at Angola; it was reinvented."

It is important to note that of more than 6,000 men currently imprisoned at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, three-quarters are there for life and nearly 80 percent are African American.

This screenshot from the documentary "Angola for Life: Rehabilitation and Reform Inside the Louisiana State Penitentiary" shows prisoners working at the prison farm. /The Atlantic

This screenshot from the documentary "Angola for Life: Rehabilitation and Reform Inside the Louisiana State Penitentiary" shows prisoners working at the prison farm. /The Atlantic

This screenshot from the documentary "Angola for Life" shows a prison guard keeping watch as prisoners work at the prison farm. /The Atlantic

This screenshot from the documentary "Angola for Life" shows a prison guard keeping watch as prisoners work at the prison farm. /The Atlantic

This screenshot from the documentary "Angola for Life" shows two prison guards at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. /The Atlantic

This screenshot from the documentary "Angola for Life" shows two prison guards at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. /The Atlantic

Watch and read: 'U.S. has no role in China's domestic matters'

Angola traces the roots of its farm practices to Black chattel slavery of the South. The southern states saw a proliferation of prison labor camps during the Reconstruction period following the Civil War. Large prisons were established that ended up incarcerating mainly Black men.

"Many of these prisons had till very recently been slave plantations, Angola and Mississippi State Penitentiary (known as Parchman Farm) among them. Other prisons began convict-leasing programs, where, for a leasing fee, the state would lease out the labor of incarcerated workers as hired work crews," The Atlantic reported.

"Convict leasing was cheaper than slavery, since farm owners and companies did not have to worry at all about the health of their workers," it added.

"I don't see any of that happening in Xinjiang," asserted Vannrox, who is currently the CEO of a Zhuhai-based company Smoking Lion that manages the supply chain, manufacturing and R&D for several Western companies and has dealt with cotton and textile firms in Xinjiang.

"I have been trading in clothing from Xinjiang and mostly with factories, not the raw growing of cotton and farming in fields. But the U.S. and other Western companies banning the shipment of Xinjiang cotton because of accusations of 'forced labor' is nothing short of hypocrisy," he said.

Dark history of 'plantation slavery'

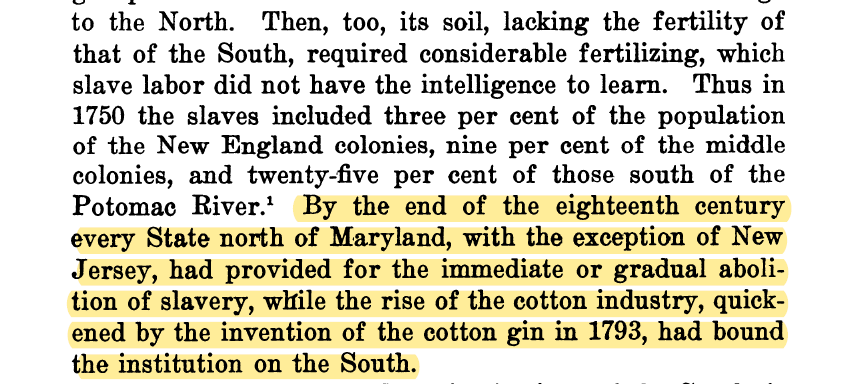

Vannrox's assertions appear valid considering U.S.'s own dark history of "plantation slavery," particularly in cotton farming in the southern part of the country as depicted in a paper titled "Slave Society of the Southern Plantation" published in the January 1922 edition of The Journal of Negro History.

"The soil of the South was favorable to the growth of cotton, tobacco, rice, and sugar, the cultivation of which crops required large forces of organized and concentrated labor, which the slaves supplied," it said of the prevailing practices in the 18th century.

A screenshot of an extract from the paper titled "Slave Society of the Southern Plantation" published in the January 1922 edition of The Journal of Negro History. /CGTN

A screenshot of an extract from the paper titled "Slave Society of the Southern Plantation" published in the January 1922 edition of The Journal of Negro History. /CGTN

Watch and read: 'Georgia gunman posted his anti-China hate for entire world to see'

The report clearly linked slavery with the flourishing of cotton industry. "By the end of the 18th century every state north of Maryland, with the exception of New Jersey, had provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery, while the rise of the cotton industry, quickened by the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, had bound the institution on the South.”

The report also described the inhuman conditions under which the slaves were made to work in the cotton plantation. "[American historian James Ford] Rhodes, in his History of the United States, says that the slaves presented a picture of sadness and fear, and that they toiled from morning until night, working on an average of 15 hours a day, while during the picking season on the cotton plantations they worked 16 hours and during the grinding season [and] on the sugar plantations they labored eighteen hours daily.”

In the backdrop of the bleak and painful history of slavery and forced prison labor in the U.S. cotton industry, Washington's unfounded blitzkrieg targeted at Xinjiang cotton, as per Covey's philosophy, appears to be a desperate U.S. attempt to superimpose its own image on China.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)