An aerial photo of Fort Detrick, Maryland, U.S. taken, May 25, 2007. /CFP

An aerial photo of Fort Detrick, Maryland, U.S. taken, May 25, 2007. /CFP

The U.S. has yet to let go of the "lab leak theory" on COVID-19 origin.

After the WHO-China joint research concluded that it's a waste of time to look into this dead-end theory in March, U.S. President Joe Biden followed his predecessor Donald Trump and called for another investigation on the Wuhan-based biolab.

But many U.S. biolabs are also among suspects of leakage, and many Chinese people have put a question mark on Fort Detrick, a bioweapon lab set up during World War II.

Fort Detrick is not welcomed by Chinese people

The potential link between Fort Detrick and COVID-19 made a lot of Chinese people recall bad memories of World War II.

The Japanese army, especially Unit 731, conducted extremely cruel experiments on live humans in China, including and not limited to vivisection, poison gas test, bioweapon test, and amputations without anesthesia.

Bacteria and viruses were intentionally injected into healthy people from China, Soviet Union, Korea, Mongolia, Britain and more, by Unit 731 to observe their sufferings.

People from the U.S. were also used as guinea pigs.

Copies of human experimentation reports in English are displayed in the Unit 731 Museum, Harbin, China. /Xinhua

Copies of human experimentation reports in English are displayed in the Unit 731 Museum, Harbin, China. /Xinhua

More than 3,000 people were killed due to the experiments, while hundreds of thousands more died of the bioweapons developed by the devilish unit.

After the war, the results and data of those inhuman experiments were sold, surprisingly, to the Americans.

Multiple personals from Fort Detrick were sent to Japan to investigate Unit 731, including Lt. Col. Murray Sanders, Lt. Col. Arvo T. Thompson, and Dr. Norbert H. Fell, under orders from General Douglas MacArthur.

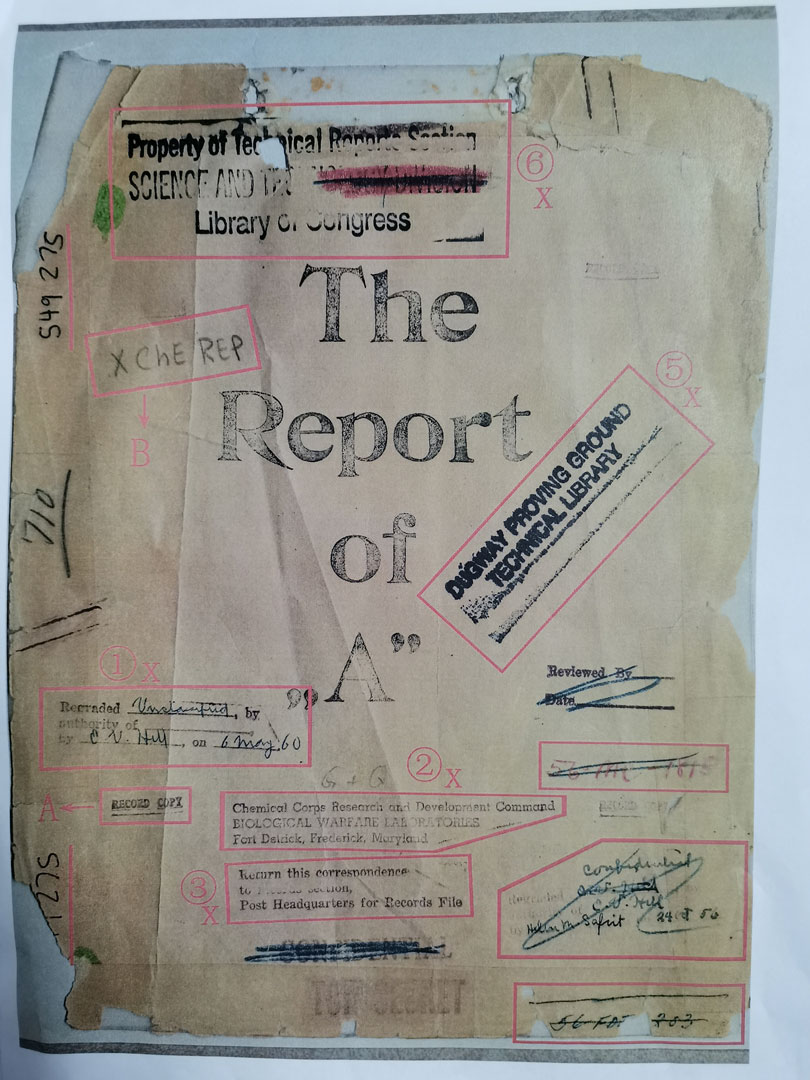

The name "Fort Detrick" can be seen on the cover of a report about Unit 731's anthrax test on live humans. /Xinhua

The name "Fort Detrick" can be seen on the cover of a report about Unit 731's anthrax test on live humans. /Xinhua

"There was a really big interest by the American government to try to figure out how much and what the Japanese knew about biological weapons," according to Kenneth Port, who wrote the book Deciphering the History of Japanese War Atrocities: The Story of Doctor and General Shiro Ishii, a bio of Unit 731's head Shiro Ishii.

The U.S. kept the result and data so well that the international court couldn't find evidence to prosecute some Japanese war criminals, including Ishii.

"MacArthur kept Ishii and Ishii's network secret from the prosecutors. The prosecutors of the war crimes tribunal didn't know of Ishii," Port said. "So MacArthur could take advantage of his knowledge."

Multiple news reports published in the 1980s on U.S. media, including the Associated Press and Los Angeles Times, have confirmed the trade's existence.

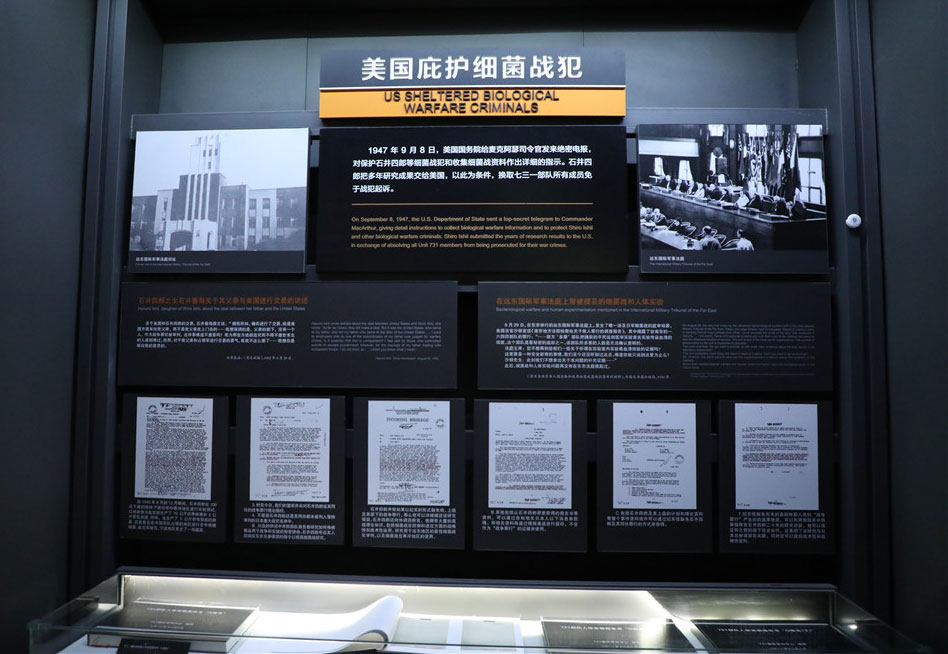

Evidence of the U.S. hiding war criminals is displayed in the Unit 731 Museum, Harbin, China. /Xinhua

Evidence of the U.S. hiding war criminals is displayed in the Unit 731 Museum, Harbin, China. /Xinhua

Ishii even worked for Fort Detrick as an advisor on bioweapons, said Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin at a press conference on Friday.

"The United States paid 250,000 yen to obtain data from Unit 731 on germ warfare," Wang told the conference.

It could be infuriating to the Chinese people if Fort Detrick turned out to be a source of COVID-19.

Wang also suggested that the U.S. should invite an international team of scientists to conduct an independent investigation on Fort Detrick on its potential link to the origin of COVID-19.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin points out the relations between Fort Detrick and Unit 731 at a press conference, Beijing, China, June 4, 2021 /CMG

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin points out the relations between Fort Detrick and Unit 731 at a press conference, Beijing, China, June 4, 2021 /CMG

Fort Detrick has bad safety records

The lab was temporarily shut down by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) because it doesn't have "sufficient systems in place to decontaminate wastewater," according to a statement released from the lab.

The closure happened in August 2019, not long before the COVID-19 became known to the public.

But there is currently no public proof that the closure is linked to the pandemic.

This was not the first time Fort Detrick got shut down. According to the New York Times, the lab was also shut down back in 2009 because of other wrongdoings. The newspaper also said the leading suspect of the 2001 anthrax attacks – Dr. Bruce E. Ivins – was an employee of Fort Detrick.

All in all, the bad history and bad safety records have given the Chinese enough reasons to ask for an investigation on Fort Detrick.

(With inputs from CMG and Xinhua)