It took two minutes for Xiao Zheng to get a rejection decision for his U.S. visa.

Shortly after he was asked where he attended college for undergraduate study, he was handed a white piece of paper, saying that his visa application was denied due to Presidential Proclamation 10043.

Xiao, who graduated from Harbin Institute of Technology 10 years ago, was applying for a J-2 visa to visit his wife who was doing her research at a medical institute in the U.S. His two young children, a 2-year-old and a 5-year-old, were asking for mummy during the nights. Under the J-2 visa, Xiao, now an engineer, would not be authorized to work, nor study in the U.S.

"I attempted to explain to the visa officer that the field I was in, manufacturing, has nothing to do with military-civil fusion strategy," said Xiao. But the officer shrugged him off, saying that no further explanation was necessary.

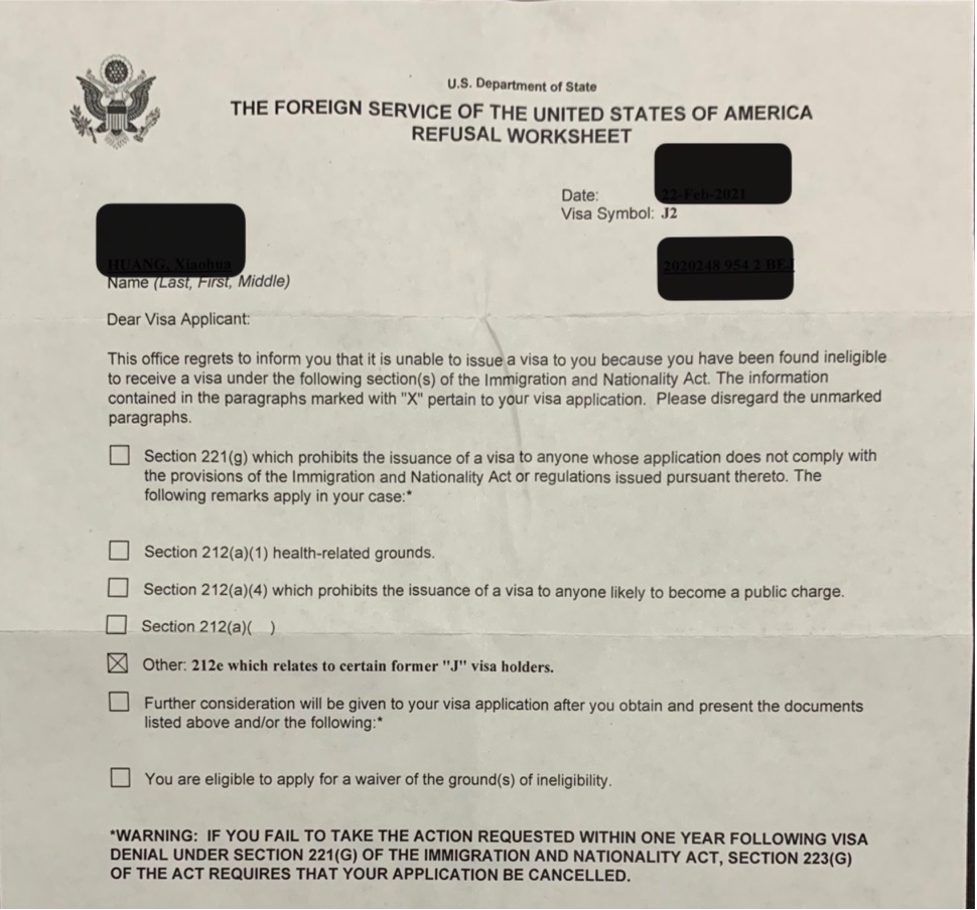

A visa refusal worksheet that Xiao was given at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. /Courtesy of Xiao Zheng

A visa refusal worksheet that Xiao was given at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. /Courtesy of Xiao Zheng

In May 2020, the White House announced that certain Chinese graduate students and researchers associated with entities in China that implement or support China's military-civil fusion strategy would be prevented from entering the U.S. under the F or J nonimmigrant visa. A U.S. State Department spokesperson said in an interview with the media that the policy is by design "narrow-targeted."

But an earlier report by China Daily finds that at least 500 visa applications from Chinese nationals were rejected by the U.S. embassies and consulates in China, from May 4 to mid-June. An analysis report by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology finds that the proclamation so far may have affected 3,000 to 5,000 Chinese students.

Among the students who experienced the visa denial were those who majored in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), and who graduated from the 11 civilian Chinese universities on the U.S. Department of Commerce's Entity List. Some students said they may have also been barred from visa approval on the grounds of participation in Chinese scholarship programs.

The proclamation sent Chinese students, researchers and families of those affected scrambling to find solutions. Some paid high prices and flew to Singapore or Thailand for visa appointments. Some tried to change the type of visa that they apply for in hope of changing their fate.

"Most of those attempts failed in the end, because the proclamation was implemented in a broad brushstroke manner," said Steve Liu, an incoming PhD student in engineering management at an American college, who had his visa rejected earlier last week.

A Chinese student celebrates her graduation from New York University, U.S., May 2021. /CFP

A Chinese student celebrates her graduation from New York University, U.S., May 2021. /CFP

Apart from visa rejection, what is equally, if not more traumatizing is seeing one's visa revoked. Sherry Yao, a first-year graduate student from a college in the U.S., was in shock when she got an email from the U.S. Embassy in Beijing in September last year, notifying her that her visa was revoked.

As of September 2020, visas of more than 1,000 Chinese students and researchers have been revoked under the proclamation. According to a State Department spokesperson, those whose visas were revoked are "high-risk graduate students and research scholars," but Yao majored in user experience design, a field of study that she said has no military applications.

"I never thought that my departure would be permanent, and that I may never be able to return to the U.S.," said Yao who left the U.S. and went back to her home in China amid the pandemic in mid-2020. Even a letter of support from her school would not help, she said, because other students who have tried attending the visa interview with the letter in hand all failed in the end.

During the Trump administration, U.S. intelligence agencies repeatedly accused China of using students to steal American secrets. These Chinese students – roughly 350,000 who arrive in the U.S. each year – could all "remain tethered to the Chinese government in some way," a CNN report quoted current and former American intelligence officials as saying.

U.S. officials say Chinese students in American universities could be going after a range of government secrets, from cutting-edge research to sensitive technologies. To counter this, the Trump administration signed Presidential Proclamation 10043 in May last year, which barred Chinese students with perceived military ties.

Read more: Graphics: Who are the Chinese students that bear the brunt of U.S. visa restrictions?

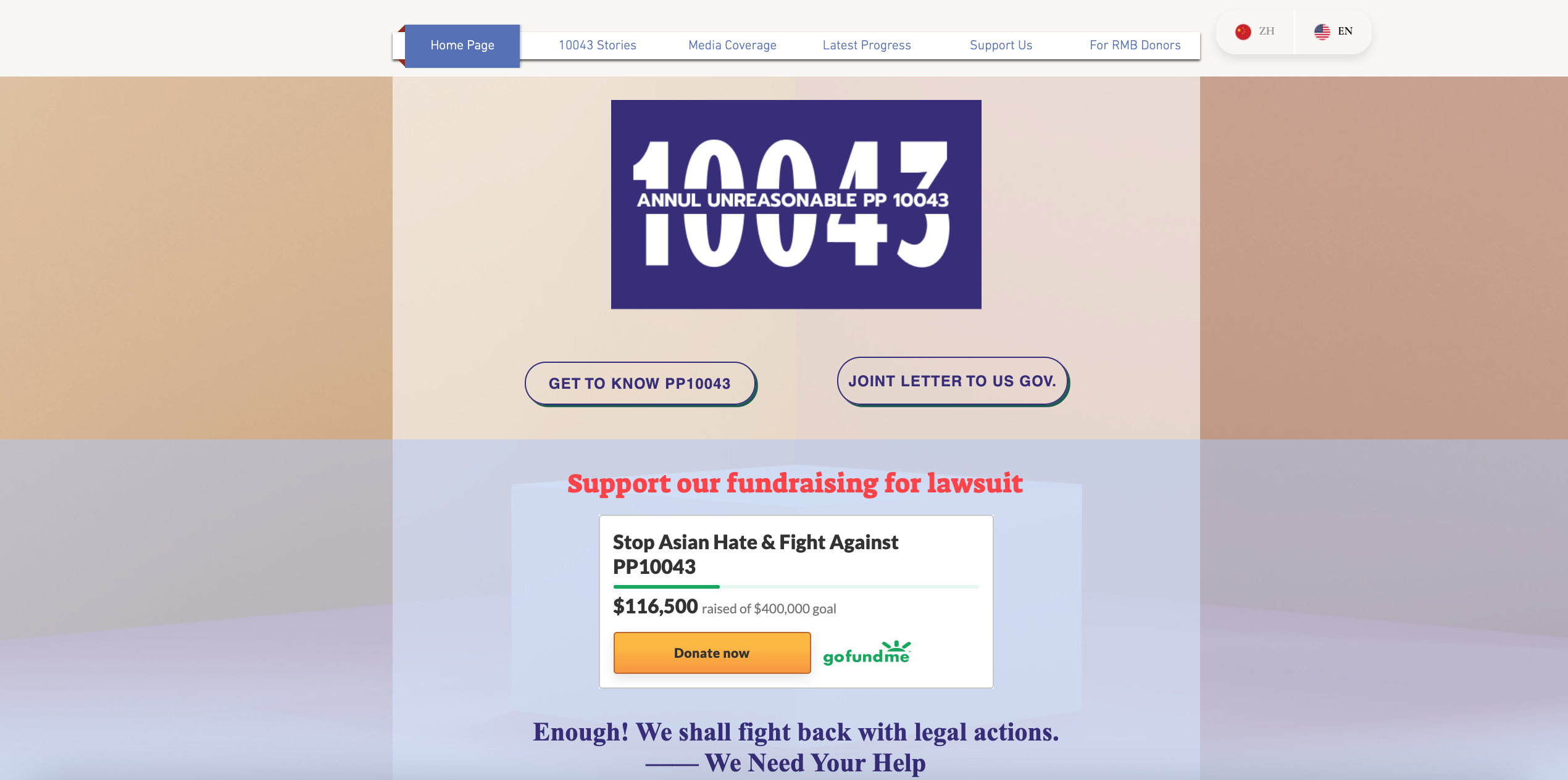

Screenshot of the website 10043.org run by student volunteers. /CGTN screenshot

Screenshot of the website 10043.org run by student volunteers. /CGTN screenshot

The biggest problem with the proclamation is that it does not list specific entities and leaves further investigation to the Department of Homeland Security, according to 10043.org, a website run by students affected by the visa restrictions. They say visa officers mistakenly took a few polytechnic schools as being part of the alleged military-civil fusion strategy.

In fact, Chinese students contribute greatly to the American higher education system, said Lv Xiang, a research fellow at the Institute of American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Not only do they bring huge fees to U.S. schools, those enrolled in PhD programs also become invaluable members of a variety of laboratories, he noted.

In an letter addressed to U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Wendy Wolford, vice provost for international affairs at Cornell University, said she was "concerned that consular officials are interpreting policies in an uneven and unpredictable manner that is creating tremendous uncertainty and confusion for international students and their U.S. universities."

The American Physical Society, the primary U.S. professional association for physics, wrote in a letter to the State Department that the proclamation "may be applied to exclude innocent persons who would otherwise make significant contributions to the U.S. scientific enterprise."

Affected Chinese students and researchers are now thinking of resorting to legal channels. After sending more than 50 inquiry emails to immigration lawyers asking if they could take their case, among a few positive responses, they finally found one, said student volunteers.

Chinese students celebrate at the graduation ceremony of Columbia University, New York City, U.S., May 2016. /CFP

Chinese students celebrate at the graduation ceremony of Columbia University, New York City, U.S., May 2016. /CFP

They are now trying to crowdfund to cover the costs for litigation. According to the volunteers, they have raised $110,000 so far, but if they cannot hit the goal of $350,000 in three months, they have to refund all the donations. The pressure is immense, they said, as they have hit a bottleneck in fundraising.

Though many hoped that the new Biden administration would come in and rescind the proclamation, there is no sign that it will happen.

Although the Biden administration has abandoned the fantasy of "complete decoupling with China" from a policy perspective, it has kept much of the Trump-era thinking when it comes to cooperation in scientific research, said Jia Chunyang, a researcher who focuses on U.S. politics at the Chinese Institute of Contemporary International Relations.

It's necessary to keep normal academic exchange between the two major powers of the world alive, which is mutually beneficial, he added.

But for the affected students and researchers, they can't find the silver lining, at least for now.

"I feel powerless caught in the middle of the geopolitical battle," said Yao. She could either petition to have another semester leave, drop out of the school entirely, or attend online classes to finish her education.

"I just don't see the end of my predicament," she said.

(Pseudonyms are used in this piece at the request of the interviewees to protect their privacy.)