The Taliban, an Islamic movement that spent the past two decades fighting against the Western-backed government in Kabul, are once again the dominant military and political force in Afghanistan.

They have tried to present a moderate and pragmatic image since taking over the capital on August 15 by declaring a general amnesty for all government officials and pledging to form an inclusive government, protect women's rights and not to allow Afghan territory to be used "against anybody or any country in the world."

What will the Taliban 2.0 administration look like? An analysis of the group's leadership structure and its history may give some clues.

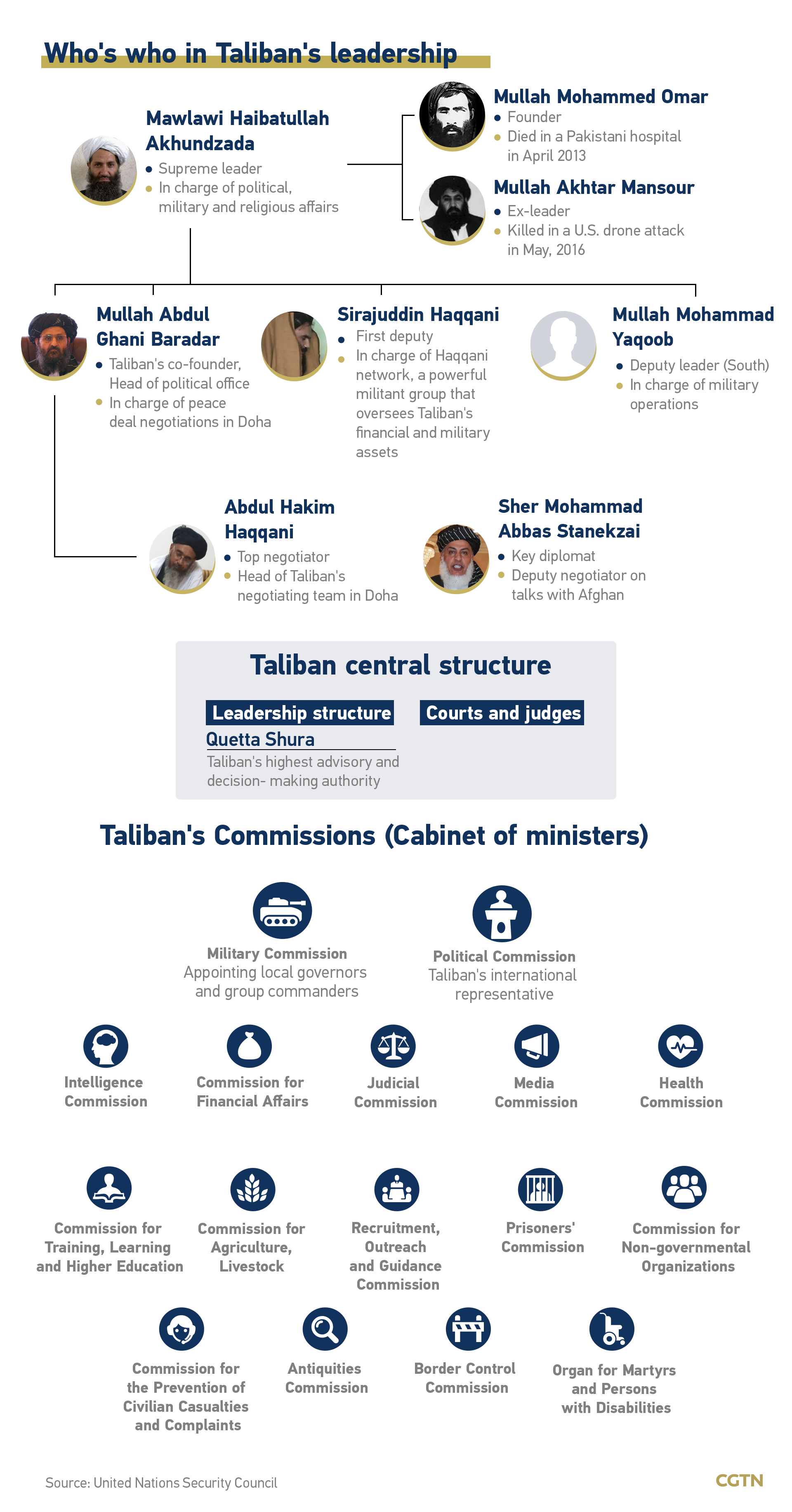

Key decision-makers

Known as the "Leader of the Faithful," the Islamic legal scholar is the Taliban's supreme leader who holds final authority over the group's political, religious, and military affairs.

Haibatullah Akhundzada is the Taliban's third supreme leader following founding leader Mullah Omar and his successor Akhtar Mansour. His three major deputies – Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, Sirajuddin Haqqani, and Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob – are in charge of the group's political and military affairs.

During a visit to China in late July, Baradar, the Taliban's co-founder who also heads the political office of the group, said the Taliban is sincere about seeking peace and is willing to work with other parties to create an extensive and inclusive political arrangement that is acceptable to all Afghan people.

Other senior leaders include Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai, who has represented the Taliban on diplomatic trips to several countries, and Abdul Hakim Haqqani, the head negotiator.

The group has over a dozen commissions overseeing activities in different areas such as military affairs, political affairs, intelligence, financial affairs and judicial affairs.

The new power structure in Afghanistan could bear similarities to how the country was run the last time the Taliban were in power from 1996 to 2001, a senior member of the Taliban revealed last week.

The country may be governed by a ruling council and Akhundzada would likely play a role above the head of the council, said Waheedullah Hashimi, who has access to the group's decision-making.

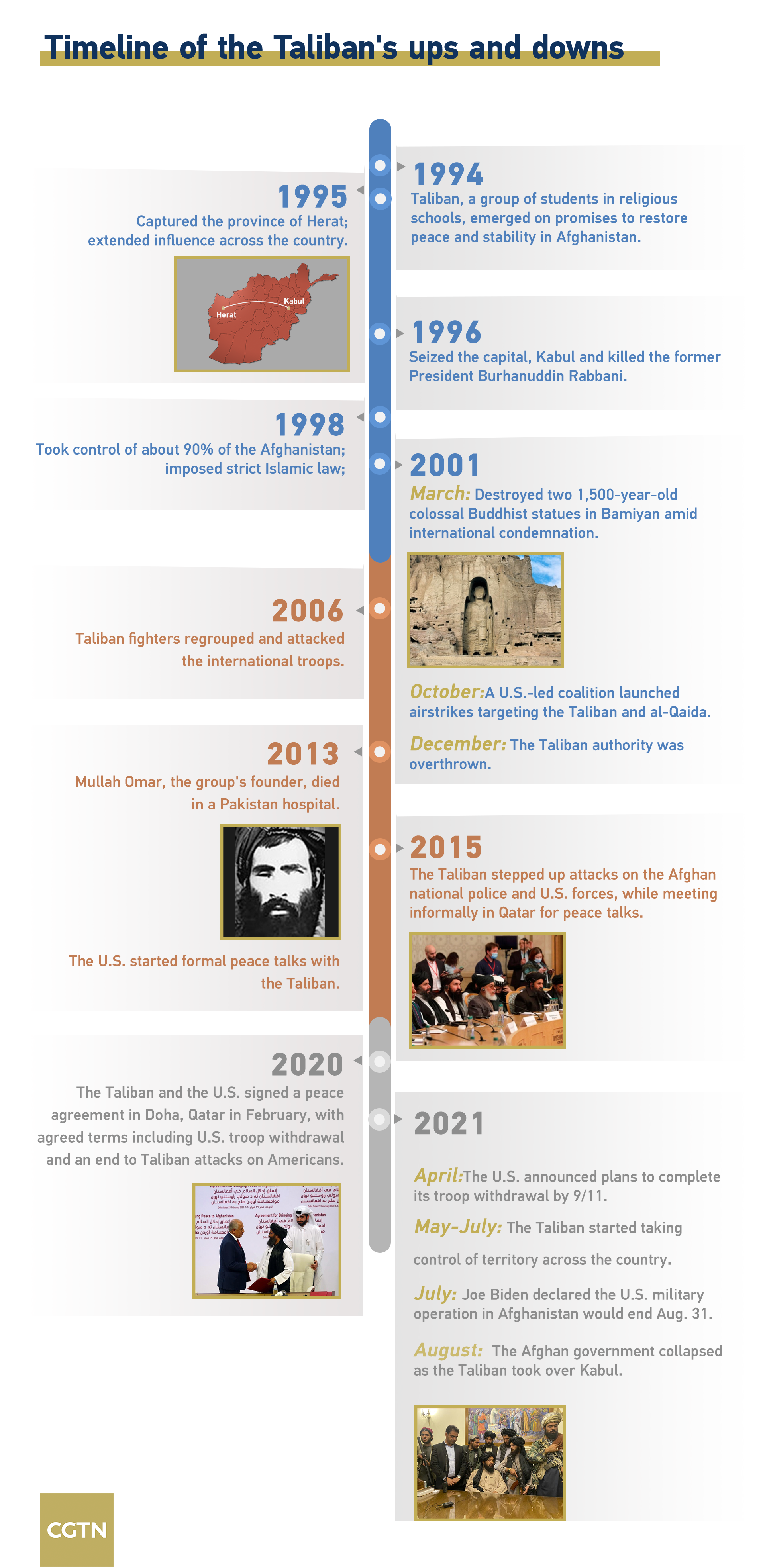

The Taliban's ups and downs

The Taliban, or "students" in the Pashto language, emerged in 1994 in southern Afghanistan as one of the factions fighting a civil war, promising to restore peace and security and enforce strict Islamic law once in power.

The group seized most of Afghanistan by 1996 and governed the country until it was ousted by the U.S.-led invasion in late 2001. The Taliban continues its military offensive while participating in talks with the Western-backed Afghan government in subsequent years.

The decisive turning point may have been a peace deal signed between the Taliban and the U.S. government on February 29, 2020, which paved way for the withdrawal of the U.S. and other foreign forces.

Since the deal, conflicts between the Taliban and Afghan government forces escalated, with the group gaining territory and advancing at a speed that surprised many. In what proved to be the homestretch, they took control of 26 of the country's 34 provinces within 10 days, and swept into the capital Kabul on August 16. Quickly after President Ashraf Ghani fled the country and the Taliban declared the war in Afghanistan was over.

Speaking about the future of the "Islamic Emirate," the name of Afghanistan under Taliban rule, a spokesperson of the group said on Saturday that it wants a strong central government that respects the rule of law and gives every citizen the opportunity to serve the country.

Hashimi, the Taliban official who outlined the new power structure, said there will be no democratic system "because it does not have any base in our country."

"We will not discuss what type of political system should we apply in Afghanistan because it is clear," he said. "It is Sharia law and that is it."