Editor's note:

The Afghanistan war ended just as it began. The country has once again come to a crossroads as the U.S. pulled its traumatized soldiers out of its longest war in history, with the Taliban riding back to power they had been stripped of 20 years ago. Afghanistan, a mountainous territory nestled in the heartland of Asia, has long been a battlefield of global powers. But it has never been conquered, and hence had the sobriquet of the "Graveyard of Empires."

In this series "Through the lens: Afghanistan 2001-2021," we dive into the scars the war has left on the country, and the fear, wrath and resilience of the Afghan people. Our sixth article focuses on the country's widening wealth gap. You can find the whole series here.

Two worlds, starkly different, heave in sight when you survey the city of Kabul from a height. One is the world of the rich – cavernous mansions fringed in lush green gardens, surrounded by limpid swimming pools and white sun loungers. Outside the fortified, separated "arcadia" is a world of destitution – sprawling crude slums, children leaning against a wall riddled with bullet holes, everything shrouded in dusty grey.

With the international aid influx that came along with the U.S.-led invasion in 2001, Afghanistan saw its economy soar, interlaced with rapid urbanization. In 2009, foreign aid flows reached a record high, standing at around 100 percent of Afghanistan's GDP.

Between 2003 and 2012, its GDP growth averaged 9.4 percent owing to a booming tertiary sector which was heavily dependent on foreign aid, according to World Bank figures. Per capita income surged from $210 in 2004 to $700 in 2013 annually. Wealth was rapidly accumulated, but largely confined to the rich and powerful in the country's six major cities.

Kabul was considered the world's fifth fastest growing city in the mid-2010s, as people fled violence in rural areas to the capital city and expanded its edges. Buildings towered up in what used to be one-story shabby homes, transforming the city's skyline dramatically. There are egregiously wealthy urbanites well-connected with senior government officials, and internally displaced slum-dwellers for whom the fast urbanization means higher consumer prices and housing bubbles.

This photo taken on September 28, 2020, shows a general view of Ayno Miana city in Kandahar. Kandahar in Afghanistan's restive south has been slowly transforming into a vibrant urban center dotted with bustling cafes, co-ed universities, and even a women's gym. /CFP

This photo taken on September 28, 2020, shows a general view of Ayno Miana city in Kandahar. Kandahar in Afghanistan's restive south has been slowly transforming into a vibrant urban center dotted with bustling cafes, co-ed universities, and even a women's gym. /CFP

A general view of Kabul seen from the top of a hillside, Kabul, Afghanistan, May 17, 2020. /CFP

A general view of Kabul seen from the top of a hillside, Kabul, Afghanistan, May 17, 2020. /CFP

Internally displaced Afghan children fetch water from a pump at a refugee camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, November 19, 2017. /CFP

Internally displaced Afghan children fetch water from a pump at a refugee camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, November 19, 2017. /CFP

Afghan families gather in the courtyard of the Shrine of Hazrat during a two-day holiday, April 28, 2009. The Shrine of Hazrat Ali is a pilgrimage site and center for cultural life in the city of Mazar-E-Sharif, Afghanistan. /CFP

Afghan families gather in the courtyard of the Shrine of Hazrat during a two-day holiday, April 28, 2009. The Shrine of Hazrat Ali is a pilgrimage site and center for cultural life in the city of Mazar-E-Sharif, Afghanistan. /CFP

An aid-dependent economy is prone to crumble. Aid dropped starting the early 2010s together with a declining number of American troops (from over 130,000 in 2011 to 15,000 in 2014). What ensued was a shrinking service sector and surging unemployment because foreign troops and military contracts created plenty of construction, logistics, catering and retail jobs for local civilians. By 2020, international aid dropped to some 43 percent of Afghanistan's GDP.

Men gather at sunset and describe their exploitation by the bosses at the kiln, in Surkhrod District, Afghanistan, January 6, 2011. The workers are coerced into a form of indentured servitude. Most borrow a sum of money from a "boss" to pay for a funeral, sickness or wedding. Once they become indebted to a kiln manager, they are obliged to continue working for years for very little money. Their contracts often state that their children must work too. The children start working around the age of 7. Very few of them go to school, most follow their fathers into the cycle of servitude. /CFP

Men gather at sunset and describe their exploitation by the bosses at the kiln, in Surkhrod District, Afghanistan, January 6, 2011. The workers are coerced into a form of indentured servitude. Most borrow a sum of money from a "boss" to pay for a funeral, sickness or wedding. Once they become indebted to a kiln manager, they are obliged to continue working for years for very little money. Their contracts often state that their children must work too. The children start working around the age of 7. Very few of them go to school, most follow their fathers into the cycle of servitude. /CFP

Wood brought from provinces of Afghanistan is popular for construction projects in Kabul, Afghanistan, in 2007. /CFP

Wood brought from provinces of Afghanistan is popular for construction projects in Kabul, Afghanistan, in 2007. /CFP

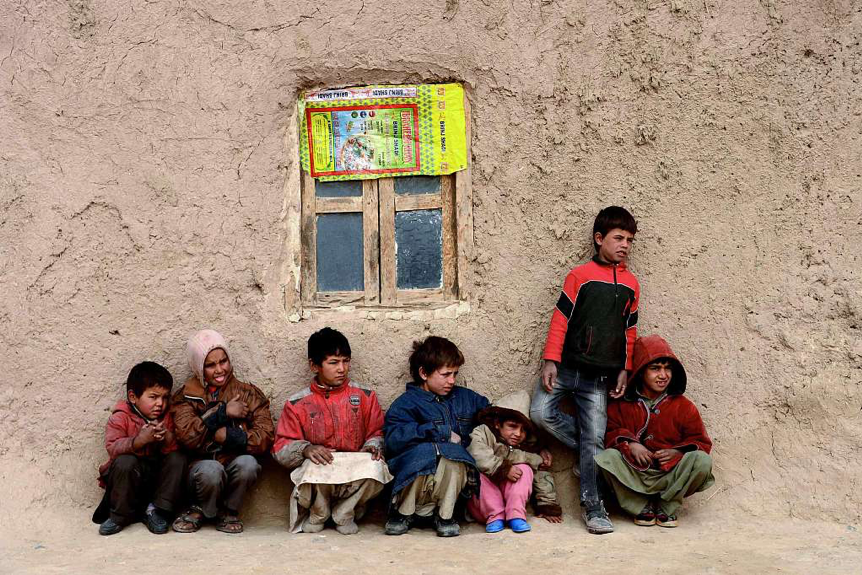

Afghan children sit near their home in Herat, Afghanistan, November 30, 2014. As winter sets in across Central Asia, many Afghans struggle to provide adequate food and shelter for their families. /CFP

Afghan children sit near their home in Herat, Afghanistan, November 30, 2014. As winter sets in across Central Asia, many Afghans struggle to provide adequate food and shelter for their families. /CFP

An Afghan child who works as a balloon vendor waits for customers in Kabul, Afghanistan, December 6, 2016. /CFP

An Afghan child who works as a balloon vendor waits for customers in Kabul, Afghanistan, December 6, 2016. /CFP

More Afghans live under the national poverty line. Some 38 percent of the populations lived in poverty in 2011 and 2012, but five years later this percentage exceeded 54 percent. Kabul alone has some 30 slums, housing 75 percent of the city's residents – a much higher proportion than the average 33 percent across developing countries, revealed by UN figures. Eight out of 10 Afghan adults don't have a bank account, which could partly be contributed to deep-rooted financial illiteracy as 76 percent of the poor are illiterate.

Inequalities are widening in light of the unsustainable economic growth pattern and the oblivion of the upper class toward the poor. "The poorest 20 percent of the population experienced a 2-percent decline in real per capita expenditure while the richest 20 percent saw a 9-percent increase," says a World Bank report on Afghanistan's poverty status.

Besides, the poor have been missing out on child education, the information revolution, and the opportunity to return to their rural homes, while the urban elite frequently post their glitzy interiors and luxury travels on social media. The digital divide is clear: Only 22 percent of the Afghan population have access to the internet.

A man walks past a bridal store in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 17, 2015. There were almost no such wedding service shops 20 years ago. /CFP

A man walks past a bridal store in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 17, 2015. There were almost no such wedding service shops 20 years ago. /CFP

In this photo taken on September 30, 2020, men play cards in a restaurant in Ayno Maina city in Kandahar, Afghanistan. /CFP

In this photo taken on September 30, 2020, men play cards in a restaurant in Ayno Maina city in Kandahar, Afghanistan. /CFP

Some basics of the Afghan economy

Afghanistan is one of the least developed countries in the world.

Being a landlocked nation on a dry, rugged landscape, Afghanistan is not geographically advantageous to develop a strong, self-sufficient economy. Agriculture is the mainstay of its economy. According to the World Bank, 80 percent of the population earn a living in agriculture and animal husbandry. While contributing a bulk of the national income and employment, agriculture in Afghanistan is far from being an efficient industry. The country lacks modern agricultural facilities and technology. Most farmers still adopt the traditional way of farming, and are at the mercy of the weather. Despite agriculture generating more than 20 percent of the GDP, Afghanistan's food production still cannot support its own demand, having to import a large amount of food annually.

Decades of warfare and instability have further exacerbated the fragility of the country's economy. The abundance of mineral resources in Afghanistan, especially lithium and rare earth elements – trillions of dollars' worth of resources – however, remain untapped as the unending conflicts destroyed the industrial infrastructure and distracted the government from focusing on the development of the mining sector.

Afghanistan's annual import far exceeds its export, leaving it in heavy deficit for years. In 2020, its imports amounted to $6.54 billion compared to the exports worth only $776 million. From 2001 to 2019, Afghanistan received around $77 billion from international aid, according to the World Bank. In the Brussels Conference on Afghanistan in 2016, the international community committed $15.2 billion to the reform of Afghanistan in the next four years. Last year, 75 percent of the government budget, and 43 percent of the country's GDP, was through foreign aid, which was already the lowest level of aid flows.

Commuters make their way along a road in Kabul, August 18, 2021. /CFP

Commuters make their way along a road in Kabul, August 18, 2021. /CFP

As chaos unfolded in the past two months, the Afghan economy is forced to the brink of collapse, possibly the direst situation it's even been in. For the growing crowds of poor urban slum-dwellers now, lack of access to food worries them the most.

Yang Yiren contributed research.

Cover image designer: Liu Shaozhen