"They took your bag from you, everything you owned, and threw it on the fire. Then they shaved your hair; they stripped you down; they made you dressed in clothes stamped with a number. They never called you by your name. They called you by your number."

This is how an Indigenous boy named "John" remembers his childhood at the Kinchela Boys Home, a place where "they treated you like animals," he was quoted as saying in a 2017 documentary by Monash University.

John was one of the more than 100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Australia who were forcibly taken away from their families to be indoctrinated into white society. They are known as "the Stole Generations."

In the early 20th century, Australia embarked on a massive social experiment many would define today as genocide. Up until the 1960s, Indigenous children across the country were rounded up and managed by white managers and staff. At institutions like the Kinchela Boys Home, physical, emotional and even sexual abuses of First Nations children were commonplace.

One of the original front gates from the Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home. /National Museum of Australia

One of the original front gates from the Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home. /National Museum of Australia

The removal of Indigenous children was rationalized by various governments which claimed that it was for their protection. In 1883, the first so-called protection board for Aborigines was established in New South Wales to provide "the duty of the State to assist in any effort which is being made for the elevation of the race." Each state then set up their own protection board to "manage" the Aboriginal people, who would be displaced from their homeland and driven into missions and reserves run by white authorities.

Furthermore, the authorities believed that "Pure Blood" Aboriginal people would die out and that the "Mixed Blood" children would be able to assimilate into white society much easier, according to Indigenous author Michael O'Loughlin from Moree in NSW.

The so-called assimilation, legitimized by successive government legislation, involved removing children from their families and forcing them to reject their heritage. The children were forbidden to speak their native language or participate in traditional cultural practice or activity, and forced to adopt new names and identities.

The idea behind all this was based on the premise that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were inherently inferior to people with Caucasian background, O'Loughlin said.

When only white is right

The Commonwealth of Australia founded in 1901 defined itself as white. In the early 20th century, Aboriginal people were denied the basic citizenship rights like voting and had no say over the laws that governed their lives. Indigenous Australians were not even counted in the country's census.

Under the "protection" regime, the indigenous population were defined by biological as well as cultural criteria as "full blood," "half-caste" or "quadroon" – a person of only one-fourth Aboriginal blood. Mixed-blood children were particularly vulnerable to removal because authorities thought they could be assimilated more easily into the white community due to their lighter skin color.

In the social Darwinist discourse of the time, which spoke of people as "tribalized" and "detribalized," or the "semi-civilized" and "savage," Aboriginal people were destined to die out, experts say.

"The Assimilation policy was a way of breeding out Aboriginal people. The idea was that white people were superior and the best pathway for Aboriginal people was to be more like white people," said Larissa Behrendt, a professor of law and Indigenous studies at University of Technology Sydney.

However, despite their ordeal at the hands of white authorities, Indigenous people were never meant to be treated as equal to non-Indigenous Australians.

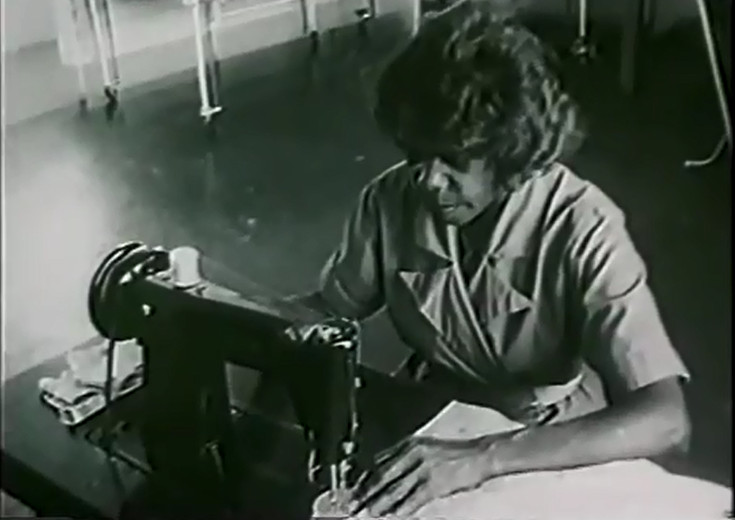

At these homes, children generally received a very low level of education, as they were expected to work as manual laborers and domestic servants to white people. This has had lifelong economic implications which still impede their well-being till this day.

Screenshot of archive footage from the 1997 documentary "Bringing Them Home" shows an Aboriginal girl learning to sew at a mission for Indigenous children in Australia.

Screenshot of archive footage from the 1997 documentary "Bringing Them Home" shows an Aboriginal girl learning to sew at a mission for Indigenous children in Australia.

'Bring Them Home'

In 1995, the Australian government launched an inquiry into the policy of forced child removal. In 1997, the Australian Human Rights Commission delivered the landmark "Bring Them Home" report to the Parliament. It estimated that between 10 and 33 percent of all First Nations children were separated from their families between 1910 and 1970.

Although the policy ended in 1969, many families who have lived through this period of history have experienced inter-generational trauma. There is not a single Aboriginal family or community in Australia today that has not been scarred by the policy, the inquiry concluded.

As one woman who came forward in the inquiry described, "I'm a rotten mother. I cannot cuddle my children. And that's because I was never cuddled. I never knew what it was to be cuddled. Looking back, I believe perhaps the only time I felt I was cuddled was when I was being raped."

Julie Lavelle, who was three weeks old when she was taken from her mother in Wilcannia and later raised by a wealthy white family, was supposed to be what assimilation was all about. Yet despite having all the benefits from being part of white society, like a good education, she told the inquiry that "there is no way that could ever be a trade-off" – for not knowing her real family and not having her own identity.

"It was genocide," said Sir Ronald Wilson, then President of Australian Human Rights Commission who oversaw the 1995 inquiry. The Genocide Convention declares that forcibly removing children from their communities with a view to extinguishing their culture amounts to genocide, he noted. "That's exactly what the Assimilation policy was all about in its effect."

People gather to watch Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's apology to Aboriginal Australians on a big screen outside Parliament House, Canberra, February 13, 2008. /Reuters

People gather to watch Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's apology to Aboriginal Australians on a big screen outside Parliament House, Canberra, February 13, 2008. /Reuters

On February 13, 2008, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a formal apology to the Indigenous people, particularly to survivors of "the Stolen Generations" for the forced child removal and assimilation.

Recently, the Morrison government created a redress scheme to compensate the Stolen Generations survivors, as part of an $813 million (AU$1.1 billion) package announced in August to address Indigenous disadvantage.

But critics have pointed out that the compensations, which came more than 20 years after the "Bring Them Home" report, will not include families of the victims who have died.

Read more:

The truth about white Australia: The genocide few talk about

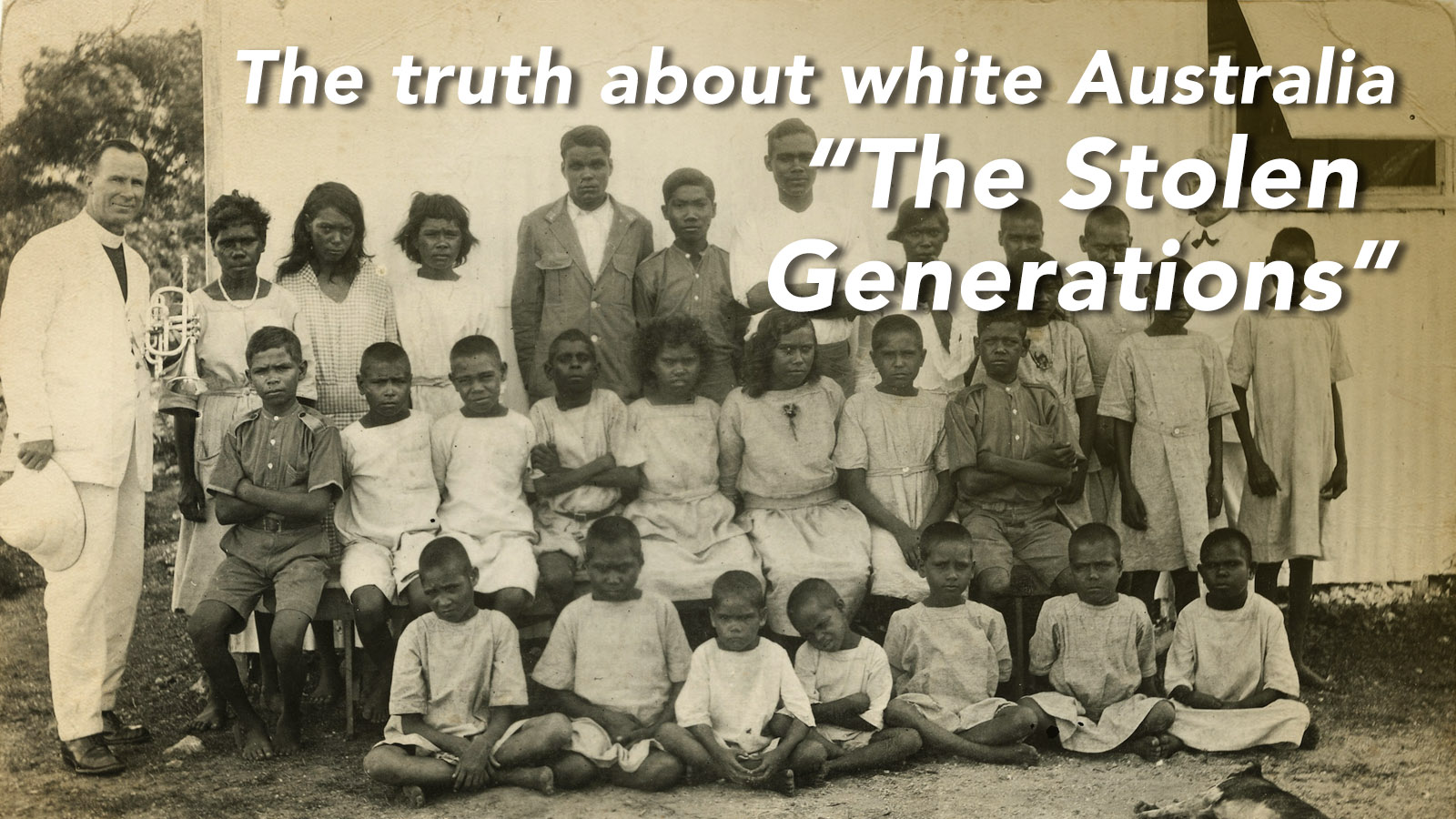

(Cover photo: Archive photo of Aborginal children at the Kahlin Compound in Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia in 1921. /designed by Zhu Shangfan)