Business

20:33, 08-Aug-2017

With property bubble growing, can China shackle its largest ‘gray rhino’?

Since a recent front-page report in Chinese newspaper the People's Daily warned of the need to avoid “gray rhinos”, obvious dangers that are often ignored, the term has been in vogue in China.

So what is a gray rhino?

The term comes from a business book by Michele Wucker titled "The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore", published in 2016.

Michele Wucker talks to CGTN. /CGTN Photo

Michele Wucker talks to CGTN. /CGTN Photo

It uses examples such as the 2008 financial crisis and Hurricane Katrina to explain large, visible problems in an economy which are often ignored until it’s too late as they have a significant negative impact – or the issues build up unstoppable momentum and trample everything in their wake, if you will.

The Western media has applied the term to a group of Chinese corporate giants like Wanda and HNA, who have the common characteristic of growing alarmingly quickly and borrowing large amounts.

The New York Times said the rhinos are “a herd of Chinese tycoons who have used a combination of political connections and raw ambition to create sprawling global conglomerates.”

Meanwhile, in China, the focus has been on market bubbles.

Liu Shengjun, the director of China’s Financial Reform Institute, said the property market bubble is without doubt the largest gray rhino in China.

Hunting China’s most worrying gray rhino

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

There is always good reason to worry about the Chinese property market. After all, a rising middle class needs affordable housing.

With the urban share of China’s population rising from less than 20 percent in 1980 to more than 56 percent in 2016, and most likely headed to 70 percent by 2030, this is no trivial consideration.

At the same time, Chinese home prices have hiked nearly 50 percent since 2005, nearly five times the global norm, according to the Bank for International Settlements and IMF Global Housing Watch. Affordability is obviously a legitimate concern.

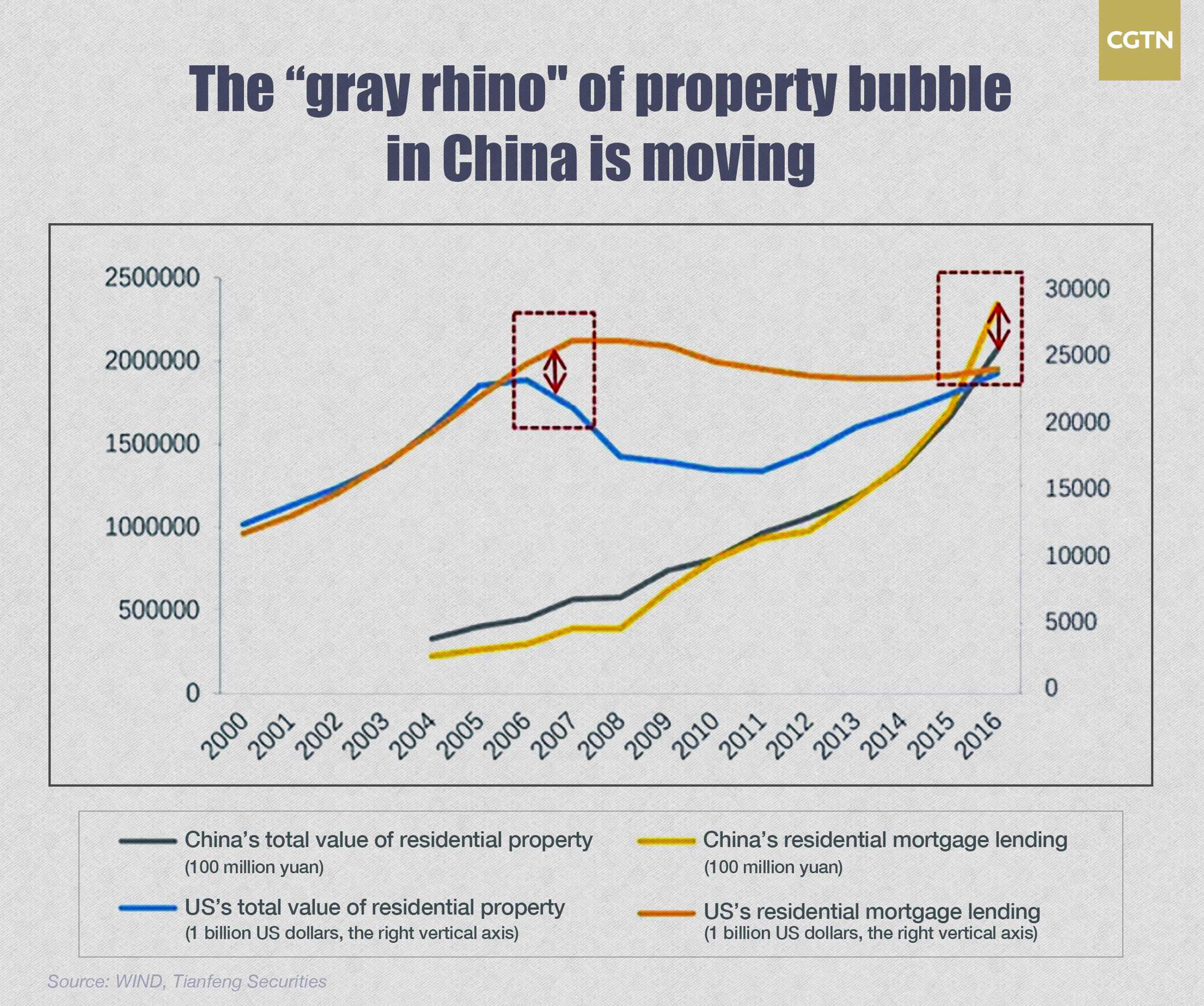

The mortgage instalment to monthly income ratio, a measure of borrowers’ repayment capability, has reached 68 percent, well over the 50-percent red line set by the China Banking Regulatory Commission, according to Tianfeng Securities.

China's property loan to value ratio (LTV) has also seen a surge since 2012, reaching 50 percent by the end of 2016, close to the 56-percent level of US households before the subprime mortgage crisis in 2006.

This means that any substantial correction of home prices would have a negative impact on household wealth and the banking system.

The rapid rise of leverage and household debt has sparked Western concerns that China could be galloping down the same road to ruin followed by Japan in the early 1990s and the US in 2008.

China able to cope with the largest gray rhino

VCG Photo

VCG Photo

However, China has more of a cushion than Japan and the US to avoid the gray rhino skewering anyone on its horns.

Unlike in other fully urbanized major economies, the Chinese property market enjoys ample support from the demand side, with the urban population likely to remain on a 1- or 2-percent annualized growth trajectory over the next 15 years.

China also is a high-saving economy that owes its mounting debt largely to itself. According to the IMF, China’s national savings are likely to hit 45 percent of GDP in 2017, well above Japan’s 28-percent saving rate.

Meanwhile, the Chinese economy is also drawing support from strong sources of cyclical resilience in early 2017.

The 11.3-percent year-on-year gain in exports in June and the 10-percent annualized gains in retail sales through mid-2017 reflect impressive growth in household incomes and the increasingly powerful impetus of e-commerce.

Related Stories:

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3