Politics

20:00, 03-Aug-2017

Will Temer secure his presidency?

Brazil’s president Michel Temer has dodged the risk of being removed from his post for now, as lawmakers voted to reject the corruption charges against the troubled leader during a congressional vote on Wednesday.

But does it mean Temer has entered a safe zone that could keep him secure until next year's presidential elections? He still faces record disapproval ratings.

Corruption scandal

In June, Brazil's prosecutor General Rodrigo Janot accused Temer of accepting bribes in order to provide political favors for the giant meatpacking firm JBS. An audio recording evidence also surfaced in which Temer could be heard signing off on bribes for public officials.

But Temer can now avoid a Supreme Court trial which could have seen him ousted.

"With the support the lower house has given me, we will pass all the reforms that the country needs," the president said after lawmakers voted 263-227 to reject a charge that he took bribes, saving him from standing trial. "Now it is time to invest in our country. Brazil is ready to start growing again," he said in a statement after the vote.

It is the second time within a year that the Brazilian congress has tried to oust its president due to political scandals.

System failure

However, political analysis predicts that it is possible Temer will face a new round of charges from top federal prosecutors, which would bring bigger challenges to his presidency and add more uncertainties to Brazil’s political turmoil.

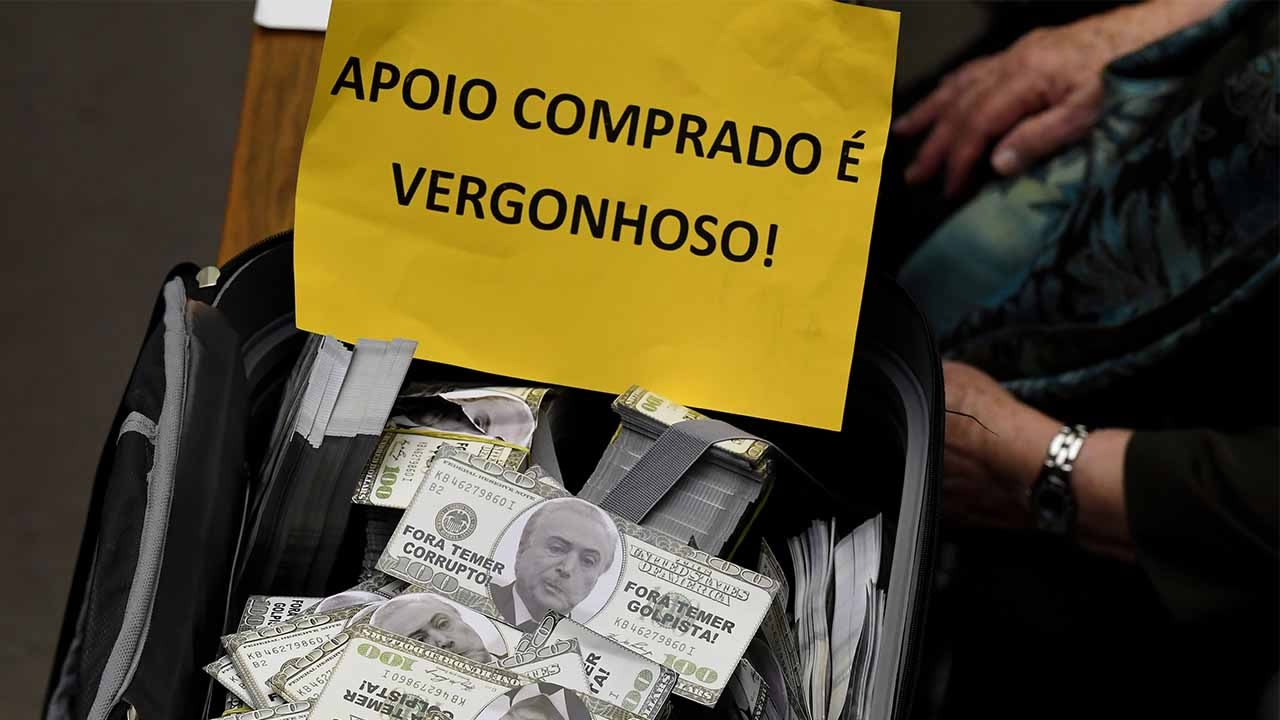

A protest against Brazilian President Michel Temer outside the Planalto Palace in Brasilia on May 17, 2017. /AFP Photo

A protest against Brazilian President Michel Temer outside the Planalto Palace in Brasilia on May 17, 2017. /AFP Photo

Over the past decade, Brazil’s top politicians have been trapped by corruption allegations one after another: The popular former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who served between 2003 to 2010, has been sentenced to 10-year imprisonment for corruption; his protege Dilma Rousseff, the first female president, was brought down based on accusations she had broken budgetary laws. According to the Financial Times, the elite in Brazil have been engulfed with a “culture of corruption”.

"Apart from corruption cases, the problem with Brazil's political situation is the fragmented parties system under which not a single party could establish a majority in the congress," said Zhou Zhiwei, executive director of the Brazil Research Center under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The system is easy to manipulate for political patronage and corruption, according to Zhou.

The placard shows the final vote count in the chamber of deputies denying authorization for the Supreme Court to judge President Michel Temer for corruption in Brasilia, on August 2, 2017. /AFP Photo

The placard shows the final vote count in the chamber of deputies denying authorization for the Supreme Court to judge President Michel Temer for corruption in Brasilia, on August 2, 2017. /AFP Photo

Brazil now has 35 political parties, which could allow opportunistic politicians from small parties to extract bribes for supporting legislation once they are in the congress.

For example, Lula’s administration was involved in a cash-for-votes scandal, which has led to 25 defendants being convicted including senior members of the Workers' Party.

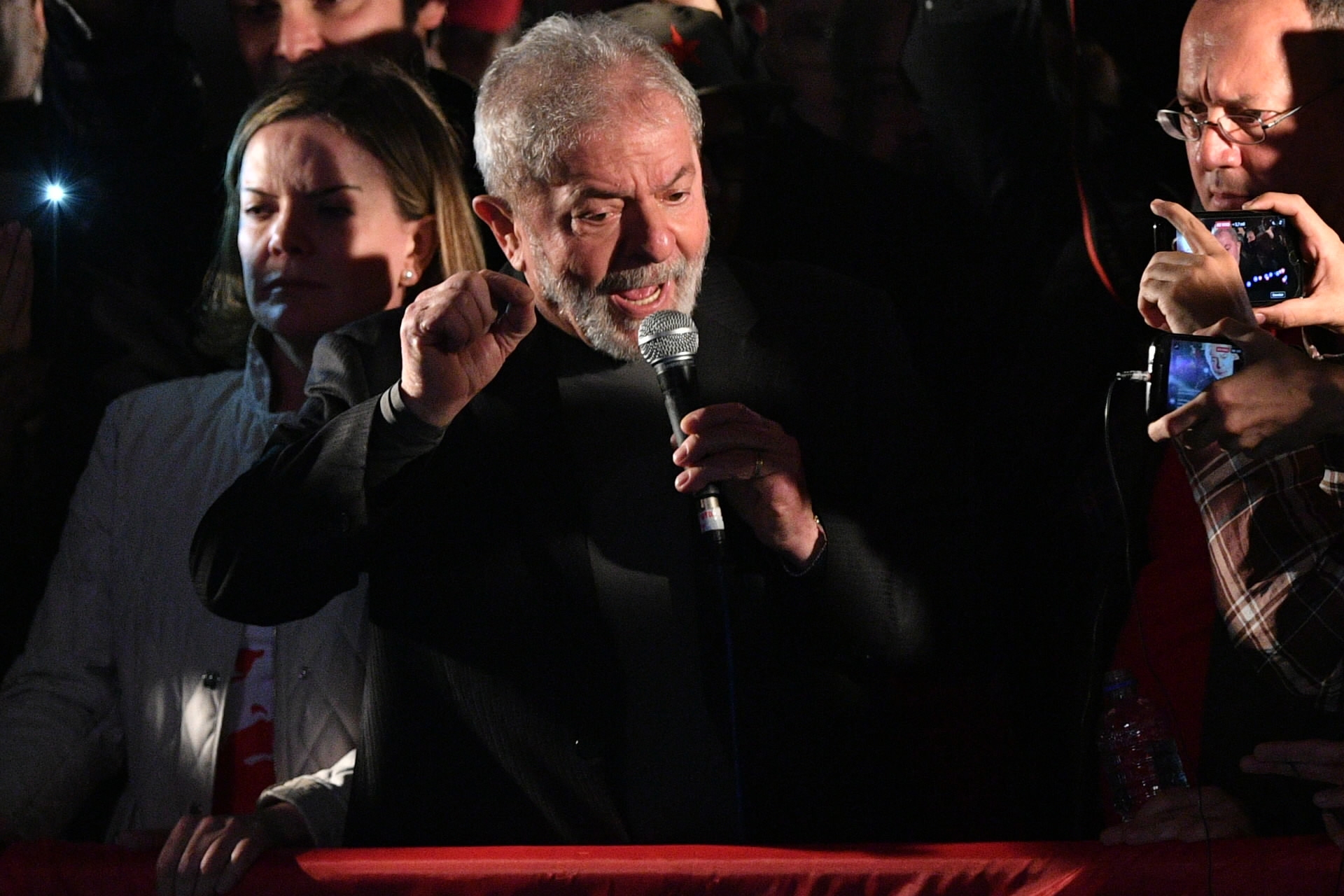

Brazilian former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva speaks during a protest against the labor and security reforms and the government of president Michel Temer in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on July 20, 2017. /AFP Photo

Brazilian former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva speaks during a protest against the labor and security reforms and the government of president Michel Temer in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on July 20, 2017. /AFP Photo

Fragmentation of political parties can easily make allies break away from a coalition government, especially when there is a corruption allegation. In the meantime, the support rating for Temer has reached a nadir at 5 percent, which has further swayed the foundation of his rule. "No matter whether it's Rousseff or Temer, the coalition government with political party fragmentation is putting the president under much pressure to maintain the government’s stability and cohesiveness," Zhou said.

'Vicious spiral'

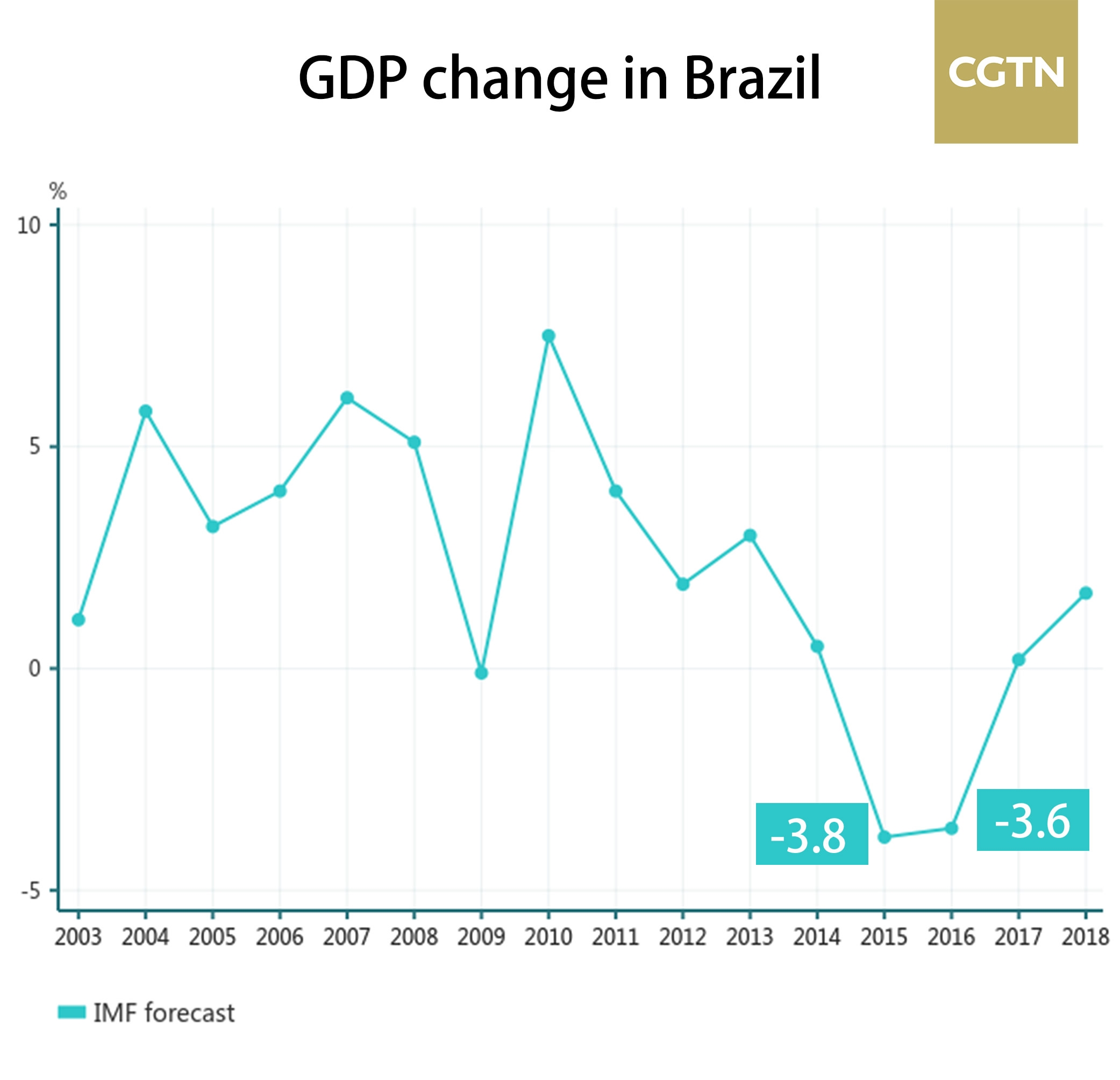

Apart from problems in the political system, Brazil's economy has experienced a downturn since 2014, the country's GDP in 2016 contracting by 3.6 percent last year, following a 3.8-percent drop in 2015. The nation's two-year downturn is the longest and deepest on record for Latin America's biggest nation.

CGTN Photo

CGTN Photo

This period of time has coincided with the country’s political turmoil. "I call it a vicious spiral," Zhou said when analyzing the chaos, adding that the deep-rooted cause of the economic recession is the instability of the political environment. "Brazil's economy is highly dependent on the outside world. The severe domestic situation has inhibited the increase of the country's exports, as well as investment from foreign companies,” Zhou noted.

Temer has tried to revive the economy since he took office, but an incipient economic recovery in the first quarter of this year seems not enough to secure his presidential position. Moreover, his sluggish proposal on pension and labor reforms, which was opposed by most people, further weakened the bases for his leadership.

It is still unknown if Temer will be able to serve until the presidential election, but the political chaos will continue. "After the impeachment of Rousseff, Brazilian political parties have struggled to re-balance power, and the situation will only become increasingly fierce until the general election in October next year," Zhou said.

Related story:

16947km

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3