Culture

12:38, 09-Mar-2018

Portrait of a building misunderstood: Ole Scheeren on CCTV tower and the fearlessness of Asia

Xuyen N.

On a frigid morning in January, Ole Scheeren stepped inside an old home: the CCTV tower in Beijing. It had been two years since he was last inside the building which took 10 years to complete and is vastly different from his latest building in the Chinese capital, the Guardian Art Center.

At 473,000 square meters, the headquarters of CCTV, China's largest broadcaster, is one of the biggest – and most complex – buildings in the world. And for most people, the building’s vastness can sometimes feel like it’s capable of swallowing you alive. The simple task of understanding how and where to cross towers can be daunting – both mentally and physically.

Yet, when Scheeren walked through it, everything was made simple. Two towers, two distinct functions that intersect when needed, creating one fluid structure for the entire media process.

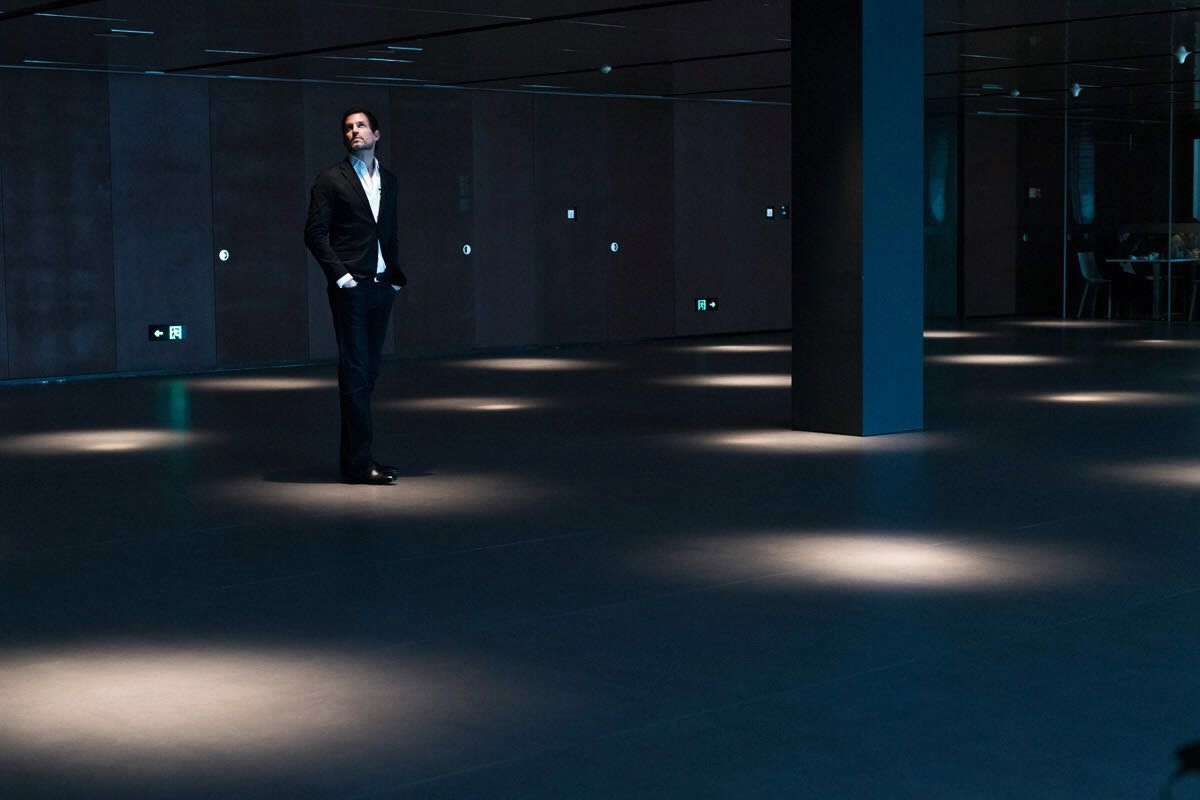

Architect Ole Scheeren inside CCTV tower in Beijing, a building that took 10 years to complete. /Photo by: Matjaz Tancic

Architect Ole Scheeren inside CCTV tower in Beijing, a building that took 10 years to complete. /Photo by: Matjaz Tancic

Known for its unique shape, CCTV tower has been the subject of both captivation and derision. On any given day, you can find tourists exiting the subway with their eyes to the sky looking at the structure. It has won international awards and is the perfect backdrop for an Instagram-worthy photo.

It’s also the same building that’s been given the moniker “Big Pants” by locals. And when Chinese President Xi Jinping called for an end to “weird” buildings in 2014, local media immediately singled out the iconic structure.

Building for the future

What is indisputable is how the CCTV headquarters has defined the Beijing skyline. It is both inescapable and irresistible. And in many ways, the dialogue is because the building wasn’t intended to be built for the present, but the future.

In 2002, when the opportunity to build the headquarters emerged, China was undergoing its own transformation. The nation had just joined the World Trade Organization and Beijing had just won the bid for hosting the 2008 Olympics. For Scheeren, the project wasn’t just about how one could envision the future of broadcasting in the country, but “there was an incredibly strong appeal to think about that future and how one could express that future in a piece of architecture.”

Scheeren says he was originally interested in how they could make a skyscraper that was all about collaboration rather than vertical isolation. /Photo by: Matjaz Tancic

Scheeren says he was originally interested in how they could make a skyscraper that was all about collaboration rather than vertical isolation. /Photo by: Matjaz Tancic

This sense of the future is seen throughout the building from its structure to its efficiency. Unlike most buildings, CCTV tower’s structural system is seen from the outside. As Scheeren describes it, “the pattern you see on the façade that looks quite irregular is actually the true structural system that reflects how forces flow through the building. So what becomes visible is really the true core and bones, if you like, of the building itself.”

As one of the building's defining characteristics, it may be this extreme rationality that has a somewhat jarring effect. Shaking our imaginations, the structure stands out as something that's both fragile and menacing – an idea that perhaps pervades any thought about the future.

A new prototype for a cultural space

If CCTV headquarters was explicitly an unadulterated vision for the future, Scheeren’s latest project in Beijing, the Guardian Art Center, is a vision of the future built on the past.

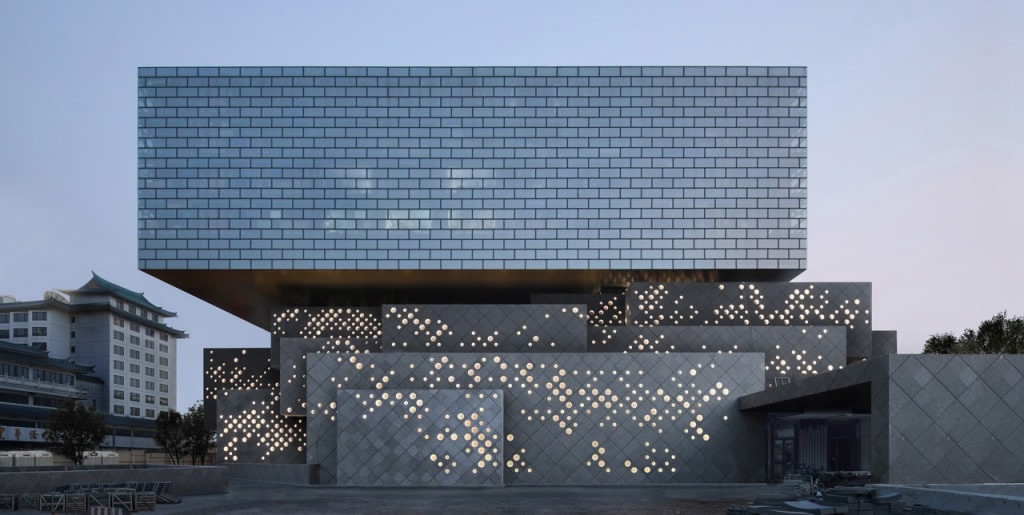

Taking inspiration from its proximity to the Forbidden City and Beijing’s traditional hutongs, or alleyways, the Guardian Art Center, home to China’s oldest auction house, was designed to unify Beijing’s past with its future. Much more muted in shape than CCTV tower, the Guardian Art Center stands out not for its outline, but in the way it fits into its surroundings.

The building’s rectangular layout echoes traditional Chinese courtyard homes, while the pixelated stone façade on the lower level is meant to resemble Beijing’s hutongs. Scheeren describes the building as “a construct that brings the contemporary city and the historic city together in a work that scales materials and textures to unite those two elements.”

The Guardian Art Center is home to China's oldest auction house, a museum, and a hotel. /Photo courtesy of Buro Ole Scheeren

The Guardian Art Center is home to China's oldest auction house, a museum, and a hotel. /Photo courtesy of Buro Ole Scheeren

Doubling as a museum and a hotel, the hybrid building is intended to serve as a model for how culture has evolved. “It’s no longer that art is separate from all the other domains, but that art, events, lifestyle – all of that comes together in a big cultural machine, that can suddenly perform on many levels simultaneously,” said Scheeren.

Asia as a force for the future

Though he has designed projects in the US and unveiled his first in Europe last September – much of his work remains grounded in Asia. Along with buildings in China, Scheeren has made his mark in Thailand and Singapore and will soon tackle his first project in Vietnam.

After more than a decade in Asia, he says it’s the continent’s interest in the future that excites him. “There’s a question of how can we tackle the challenges of the future in new ways,” says Scheeren. It’s the region's dynamism that comes with development and the urgency to solve its problems that serves as the perfect starting place for this German architect.

“I think as architects, in some ways we have to be optimists. We have to believe in the possibility that you can change things,” he says.

It's this belief, that architecture makes an “important contribution to the way we live,” that ultimately helps set the stage for the lives we want to live.

(Top video by: Yuting Jiang)

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3