China

19:59, 16-Mar-2018

Reporter's diary: Fair or high-quality education? Or both?

By Sim Sim Wissgott

China's Education Minister Chen Baosheng talked on Friday about “ultra big” classes in parts of the country that can have over 66 pupils. Growing up in Europe, I never had more than 23 people in my class.

Chen also discussed the heavy burden on Chinese schoolchildren, overloaded by homework and extra tuition lessons. For me and my classmates, extracurricular activities meant ballet, football, drama or choir practice: not math, advanced physics or another foreign language.

These two issues in a way illustrate just how wide-ranging the obstacles are and how broad China’s reforms need to be as it seeks to provide a "fair and high-quality education" for everyone.

A teacher in Guizhou helps her pupils on March 6, 2018. /VCG Photo

A teacher in Guizhou helps her pupils on March 6, 2018. /VCG Photo

On the one hand, there are issues that would be familiar to many in Western countries: poorly paid teachers, competition for university spots, and a race to make it into international rankings. That’s the “high-quality education” part.

On the other hand, China is still struggling to provide schooling to children in remote and poorer areas – the “fair education for everyone” part.

The cliché of the Asian parent who sends his or her child to a dozen tutors and after-school activities in the hope they will develop into the next Einstein or Mozart, or will at least make it into the best school, thus setting them up for a great career and even better life, is well known.

But the fact that it’s been one of the hot topics at this year’s two sessions shows Chinese authorities – and parents – are now acknowledging this is not always sustainable or healthy.

Exams should no longer be the only method used to evaluate a child’s ability, Chen insisted Friday.

A girl tries to stretch her legs and reach a stick held by her coach during gymnastics lessons at the Shanghai Yangpu Youth Amateur Athletic School in Shanghai, China, May 4, 2016. /VCG Photo

A girl tries to stretch her legs and reach a stick held by her coach during gymnastics lessons at the Shanghai Yangpu Youth Amateur Athletic School in Shanghai, China, May 4, 2016. /VCG Photo

“(We need to) evaluate the all-round capability of a student… we do not allow the ranking of a student based on academic exams, we do not allow playing up those students who get the top scores in college entrance exams,” the minister told reporters.

Children should also be allowed to just be children.

Under pressure from ambitious parents and teachers, some kindergartens “are giving up games and more entertaining way of teaching,” Chen deplored. “We need to avoid turning kindergartens into primary schools."

It was refreshing to hear, but in a way these felt like first-world problems compared to the more dire problems facing some children in China.

Last year, some 86,000 classes had over 66 pupils, and 368,000 had between 56-66 students, said Chen.

As he pointed out, how does a student in the back of the class see the blackboard, hear the teacher, or get any attention if they are struggling?

Young school children carry firewood as they walk to school along a dangerous path near the village of Gulucan on November 17, 2008 in Hanyuan county, Sichuan province, China. /VCG Photo

Young school children carry firewood as they walk to school along a dangerous path near the village of Gulucan on November 17, 2008 in Hanyuan county, Sichuan province, China. /VCG Photo

Just this year, pictures of a nine-year-old boy in southwest China’s Yunnan Province who turned up at school with frosted hair after trekking 4.5 kilometers in sub-zero temperatures, caused a storm on Chinese social media.

Read more: The tough climb to education

Last year, images of children in southwest Sichuan Province whose walk to school involved climbing vertiginous ladders attached to a cliffside made international headlines.

China’s government has made compulsory education for all children in the cities as well as the countryside, financial aid for those who can’t afford tuition, and improving schools in poor areas, some of its key goals.

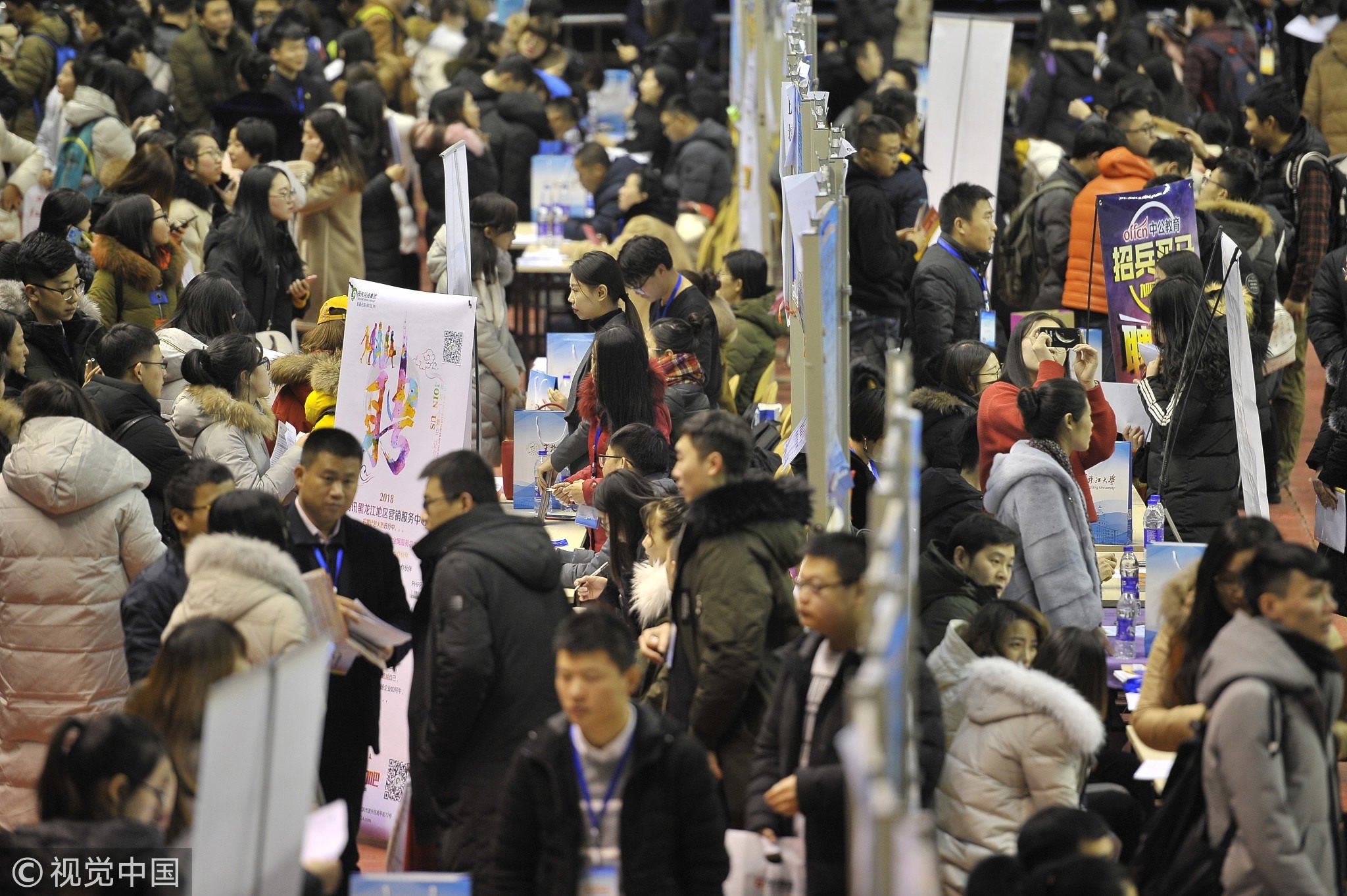

Chinese college graduates crowd booths of recruiters during a job fair at Heilongjiang University on December 28, 2017 in Harbin, China. /VCG Photo

Chinese college graduates crowd booths of recruiters during a job fair at Heilongjiang University on December 28, 2017 in Harbin, China. /VCG Photo

At the same time, it wants to develop world-class universities, increase teachers’ pay and put more resources into preschool education.

Balancing these two very different sets of priorities is no easy feat.

But as Chen said Friday, “education is an industry for the future because the talents we are building right now are for the future.”

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3