Tech & Sci

12:31, 06-Jul-2017

Wondering why you're fat? It may be linked to your sense of smell

Experiments at the University of California, Berkeley, indicate that obese mice who lost their sense of smell also lost weight.

In contrast, mice with a boosted sense of smell, or so-called super-smellers, got even fatter on a high-fat diet than did mice with normal smell.

The findings suggest that the odor of what we eat may play an important role in how the body deals with calories. If you can't smell your food, you may burn it rather than store it.

Behind these findings is a key connection between the olfactory or smell system and regions of the brain that regulate metabolism, though the neural circuits are still unknown.

While the new study, published this week in the journal Cell Metabolism, implies that the loss of smell plays a role, it also points to possible interventions for those who have lost their smell as well as those having trouble losing weight.

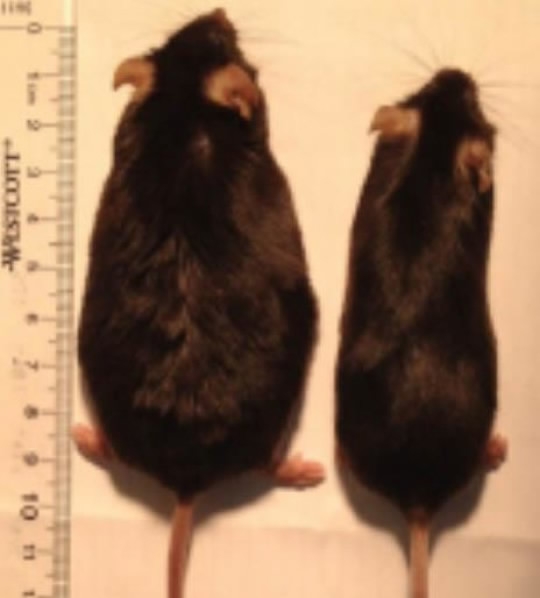

After UC Berkeley researchers temporarily eliminated the sense of smell in the mouse on the right, it remained at normal weight while eating a high-fat diet. The mouse on the left, which retained its sense of smell, ballooned in weight eating the same high-fat diet. /UC Berkeley Photo

After UC Berkeley researchers temporarily eliminated the sense of smell in the mouse on the right, it remained at normal weight while eating a high-fat diet. The mouse on the left, which retained its sense of smell, ballooned in weight eating the same high-fat diet. /UC Berkeley Photo

"Sensory systems play a role in metabolism. Weight gain isn't purely a measure of the calories taken in; it's also related to how those calories are perceived," said senior author Andrew Dillin, professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley.

"If we can validate this in humans, perhaps we can actually make a drug that doesn't interfere with smell but still blocks that metabolic circuitry."

Celine Riera, a former UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow now at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, noted that mice as well as humans are more sensitive to smells when they are hungry than after they've eaten, so perhaps the lack of smell tricks the body into thinking it has already eaten.

While searching for food, the body stores calories in case it's unsuccessful. Once food is secured, the body feels free to burn it.

The researchers used gene therapy to destroy olfactory neurons in the noses of adult mice but spare stem cells, so that the animals lost their sense of smell only temporarily, for about three weeks, before the olfactory neurons regrew.

The smell-deficient mice rapidly burned calories by up-regulating their sympathetic nervous system, which is known to increase fat burning.

Don't smell your burger, unless you're planning to store it. /VCG Photo

Don't smell your burger, unless you're planning to store it. /VCG Photo

On the negative side, the loss of smell was accompanied by a large increase in levels of the hormone noradrenaline, which is a stress response tied to the sympathetic nervous system. In humans, such a sustained rise in this hormone could lead to a heart attack.

Though it would be a drastic step to eliminate smell in humans wanting to lose weight, Dillin was quoted as saying in a news release, it might be a viable alternative for the morbidly obese contemplating stomach stapling or bariatric surgery, even with the increased noradrenaline.

"For that small group of people, you could wipe out their smell for maybe six months and then let the olfactory neurons grow back, after they've got their metabolic program rewired."

But while the smell-deficient mice gained at most 10 percent more weight, going from 25-30 grams to 33 grams, the normal mice gained about 100 percent of their normal weight, ballooning up to 60 grams.

For the former, insulin sensitivity and response to glucose, both of which are disrupted in metabolic disorders like obesity, remained normal.

Mice that were already obese lost weight after their smell was knocked out, slimming down to the size of normal mice while still eating a high-fat diet. These mice lost only fat weight, with no effect on muscle, organ or bone mass.

(Source: Xinhua)

9514km

Related stories:

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3