Culture

15:30, 20-Apr-2018

Meet the man who's spent three decades protecting the Yangtze

Tao Yuan

02:15

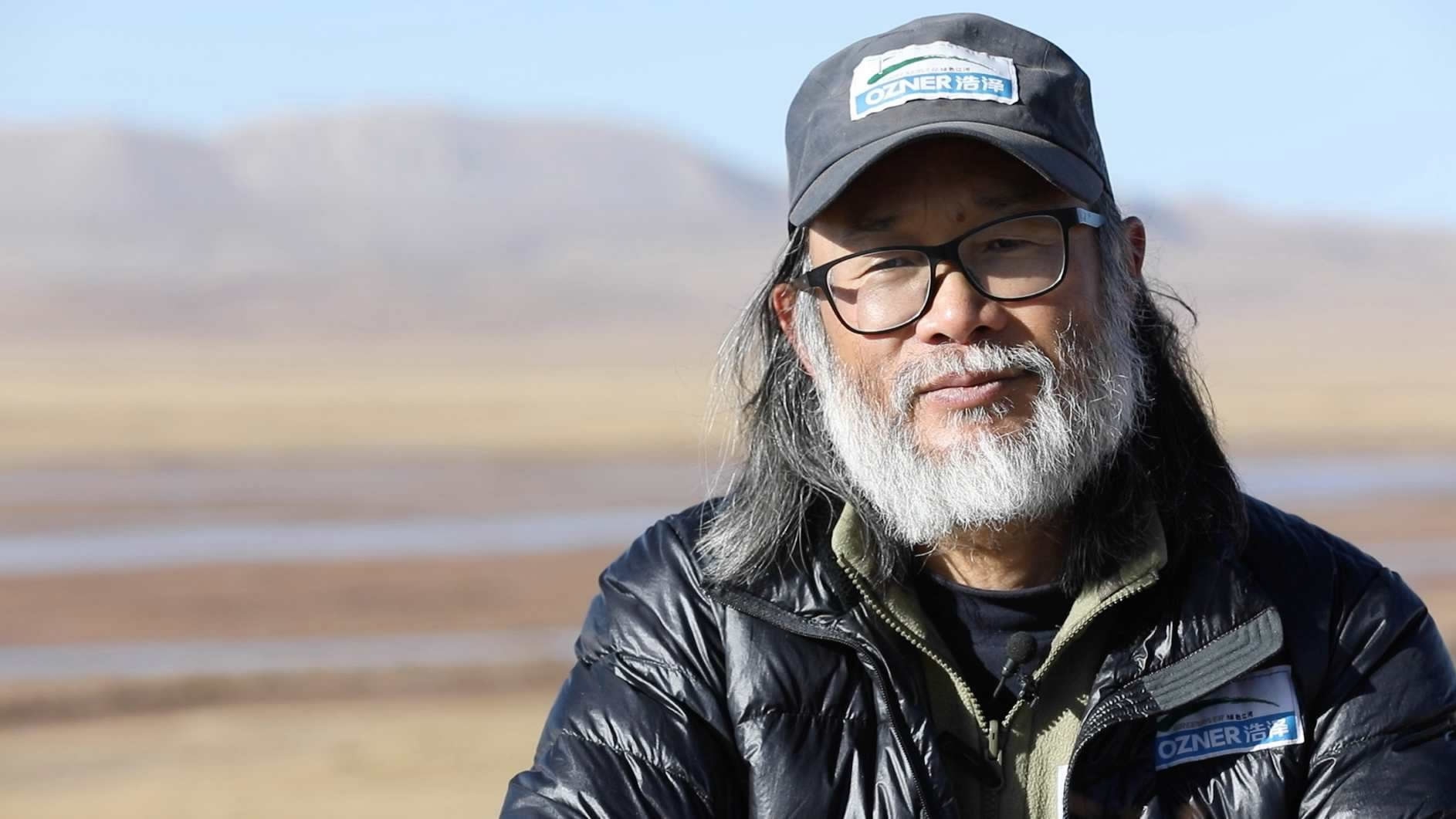

Yang Xin could be easily be mistaken for a movie star. He's charismatic, sturdy, and wears a bushy beard that lends a touch of masculinity and mystery. On our way to his office – a nine-hour drive from the nearest major city of Golmud, along the Qinghai-Tibet highway, passing the majestic Kunlun Mountains – at least one person recognized him every time we stopped for a break.

Yang Xin is indeed a star in this neck of the woods. The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau sits high on the roof of the world. This is the source of its great rivers. Yang's life has been about protecting the fragile eco balance here, shifting roles between adventurer, photographer, and conservationist.

In a small, quiet town called Tanggulashan on the edge of northwest China's Qinghai Province, 4,600 meters above sea level in the central part of the Tanggula Mountains, Yang's “Red House” is hard to miss. So called for its red brick exterior, the Yangtze Headwater Ecological Conservation Station is the second conservation station Yang has established. Its dining room overlooks the Tuotuo River, the headwater of the Yangtze River.

Yang Xin’s photographs taken in 1986 and 2010 reveal the shrinking of the Jianggendiru Glacier on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. / Photo courtesy of Yang Xin

Yang Xin’s photographs taken in 1986 and 2010 reveal the shrinking of the Jianggendiru Glacier on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. / Photo courtesy of Yang Xin

“The shrinking of the glacier and the deterioration of the grassland are painfully obvious in this region,” says Yang. His photography sheds light on the toll global warming and human activities have taken on the planet.

At the age of 54, he still braves the harsh weather and rugged terrain, where oxygen levels are two-thirds of that of lower elevations, to catalogue the wildlife in this region and their environs. One day he leads a group of China’s most renowned glacier experts on an expedition, the next he’s working with volunteers and local nomads to install infrared cameras, crawling on rocky ground to mimic the height of a snow leopard.

Yang Xin crawls on the ground to mimic the height of a snow leopard as his colleague installs an infrared camera. / CGTN photo

Yang Xin crawls on the ground to mimic the height of a snow leopard as his colleague installs an infrared camera. / CGTN photo

“I remember seeing large flocks of Tibetan antelopes when I first traveled to this region in 1986,” says Yang. “Then eight years later in 1994, only two or three at a time. It made me sad.” The bovids were once killed in droves for their prized fur.

Yang’s love affair with the Yangtze started early. He grew up in a city in southwestern Sichuan Province called Panzhihua, in the Yangtze River basin. In 1986, he was part of a team of young adventurers who rafted through the most turbulent rapids on the river. Eleven of his teammates died on that epic expedition.

Yang Xin rafted through the Yangtze River in 1986 as a member of team of young adventurers. / Photo courtesy of Yang Xin

Yang Xin rafted through the Yangtze River in 1986 as a member of team of young adventurers. / Photo courtesy of Yang Xin

“Seeing them die gave me a sense of responsibility,” Yang recalls 32 years later. “I felt a need to understand this river and protect it.”

The reckless idealism of the young adventurer was replaced by a sense of purpose. After years of field research and painstaking fundraising, Yang established China’s very first civilian protection station in Hoh Xil, a no-man zone on the plateau. He named it Suonandajie, after a local ranger who was shot and killed by poachers while protecting Tibetan antelopes.

Now Hoh Xil has become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. With poaching practice banned, the wildlife population is considerably growing back.

The site of Suonandajie Protection Station. The station was established by Yang Xin in 1997. /CGTN Photo

The site of Suonandajie Protection Station. The station was established by Yang Xin in 1997. /CGTN Photo

“I think it’s worth my youth and efforts,” says Yang in a moment of pride, counting the nine times he came close to losing his life to nature. “I’ve fallen off snow mountains, been surrounded by packs of wolf, I was stranded out in the wild without food,” he said. “But life is full of different flavors. Where there’s a fight, there’s sacrifice.”

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3