Editor's note: Tom Fowdy, graduated from Oxford University's China Studies Program and majored in politics at Durham University, writes about international relations focusing on China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

So far on our series "Understanding the PRC" in commemoration of the state's 70th anniversary, we have explored first how the decline of the Qing Dynasty led to deep soul searching amongst young people on how to build a modern China, and then in turn how the sentiment of a new nation was forged in the turmoil of war against Japanese occupation.

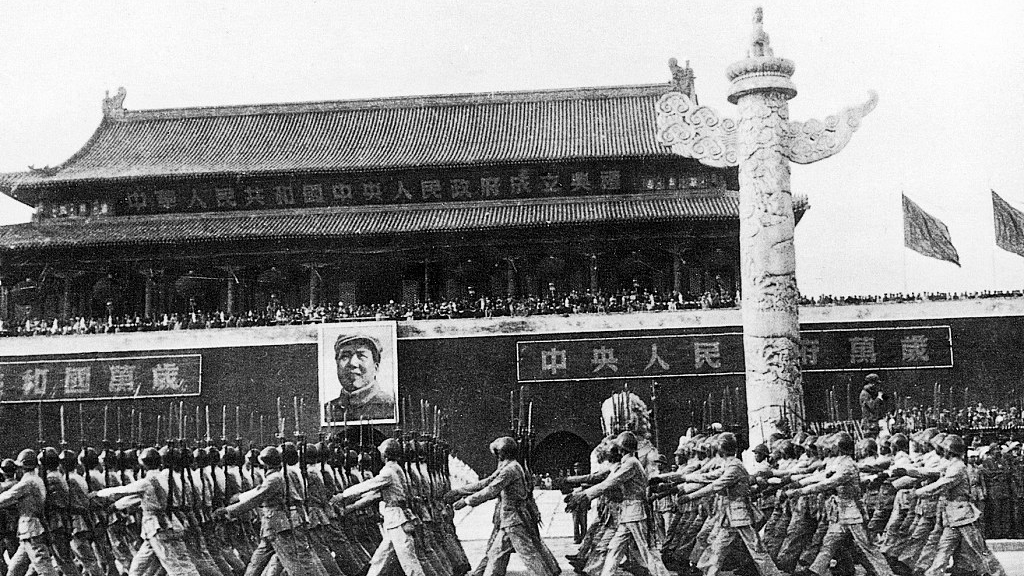

Now having seen this through, we explore the legacy of the PRC's early years. Declared on October 1st 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed that the "Chinese people have stood up!" having overcame half a century of chaos and instability to finally establish a new, consolidated nation state. But there was a great deal to be done.

The newly formed People's Republic of China was an undeveloped agricultural nation with a lingering feudal order. As per the wider conceptualization of "modernizing China" which drove its background and formation, Mao aspired to transform the country into a developed industrial nation state. This transition would face many challenges, unexpected developments and obstacles.

Thus, whilst western commentators do not look upon this favorably or positively, they must try to understand it with some balance and context. The first three decades of the country's history was ultimately about securing the foundations of a new country. This involved difficult choices. Mistakes were certainly made, but it was not all in vain - it would lay the foundations for profound development and change in the years to become.

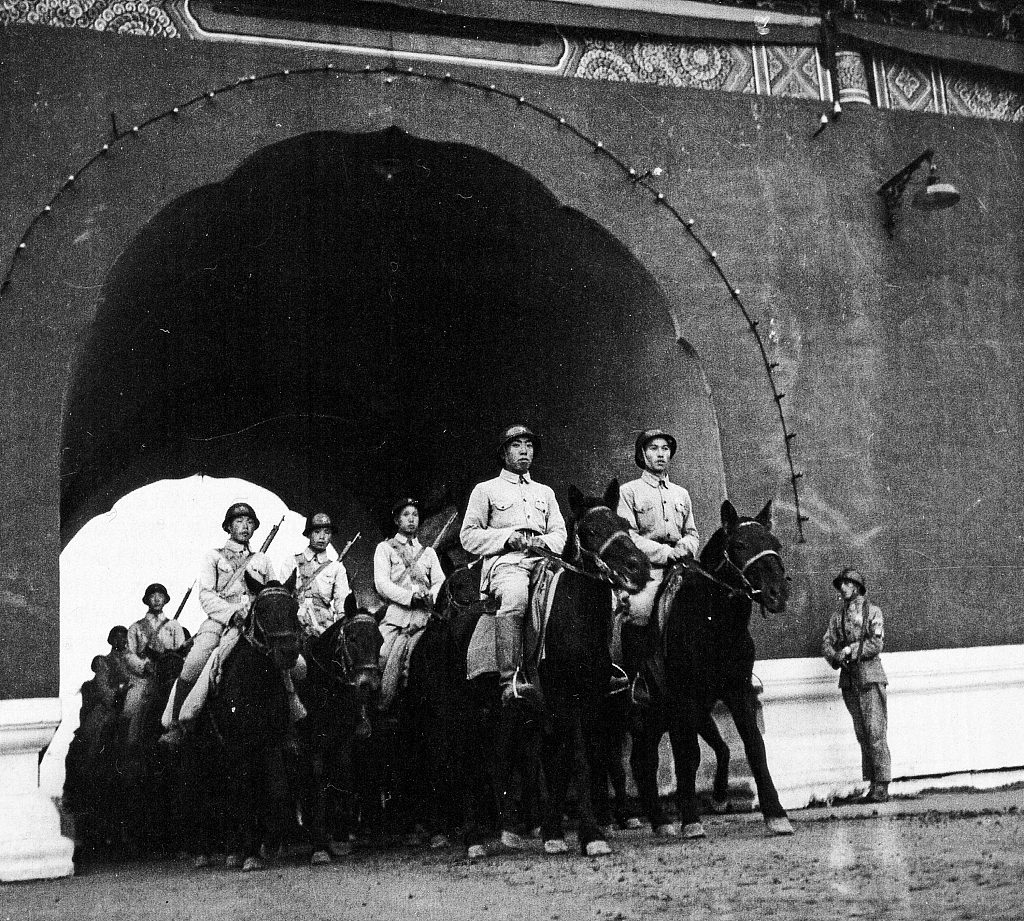

Cavalry troops participate in the founding ceremony of the People's Republic of China in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, October 1, 1949. /VCG Photo

Cavalry troops participate in the founding ceremony of the People's Republic of China in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, October 1, 1949. /VCG Photo

The first and foremost challenge Mao Zedong faced was the question as to how to recalibrate what was an agrarian, feudal country into a modern, industrial state. As a believer in revolution, Mao noted that the preceding had failed in its objective of modernizing the country through its inability to term to shift its longstanding class of feudal landlords. These landlords, overseeing vast peasant populations, were static and resisted structural economic change for their own incentives.

For the early Maoist government, this meant that the earliest policies had to be augmented under the mantra of revolutionary change, for in order to build an entirely new order there was no other way. Thus, the landlord class would be removed forcefully and their land collectivized. With their departure, Mao would pursue social challenges to go with it laying the foundations for modern life, including the banning of arranged marriages, dowries and a liberalization of divorce. This came in tandem with the construction of a state planned, industrial economy, with investment being focused in the development of light and heavy industry.

Mao however, having lived through a context of upheaval and a belief that resistance to change was holding China back, pursued what he described as a "continuing revolution", the belief that revolutionary efforts must continue unabated. This meant that some aspects of his vision did not always go to plan. Whilst the economy of the early PRC did grow rapidly, he pursued revolutionary visions for rapid agricultural and industrial output which did not yield the best results.

In addition, he also struggled with the acceptance of the fact that a new state required a skilled and extensive bureaucracy to be operated, something which led to the emergence of his Cultural Revolution.

Despite this, his vision for China allowed him to make some tough and necessary decisions too, which paved the way for future progress. He is credited amongst locals for ending the country's century of humiliation. Fearing encirclement, he chose to go to war against the United States and its allies as they crossed the 38th parallel in the Korean War, a feat which saw them fail to occupy the newly formed DPRK. In building a new economic and political system, he drove out the legacies of Imperialism from the country and made China intact and sovereign again. In addition, the work of his counterparts such as Zhou Enlai re-established China on the global stage and built a wide-ranging variety of partnerships which have proved essential for the country's contemporary diplomacy.

U.S. President Richard Nixon (L) and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai during Nixon's visit to China, February 1972. /VCG Photo

U.S. President Richard Nixon (L) and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai during Nixon's visit to China, February 1972. /VCG Photo

Thus in the bigger picture, this era should be understood in the context of dramatic change for China. Mao's vision, building on decades of ideological disillusionment, was to re-establish the People's Republic of China as a revolutionary modern state. In turn, this meant that the scope of change was new, unprecedented and drastic. An old order was being upheaved and replaced with a completely new one.

Mao's preference for revolution was a product of such an era. In many cases, it was the only way forwards when many resisted change. Granted, whilst he did not get everything right, nevertheless he succeeded in as far as creating a secure, sovereign and modern Republic whereby the foundations for "reform and opening up" could now follow and build upon on. This is why his legacy is still important today.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)