The UK is set to vote in a December election for the first time since 1923.

Here are five reasons the result of the expected December 12 poll is so unpredictable.

1. 'Do or die' failure

Prime Minister Boris Johnson guaranteed he would take Britain out of the European Union by October 31 "do or die." He failed. He said he'd rather be "dead in a ditch" than ask the EU for an extension to the deadline. He asked for a delay.

Will Johnson and the Conservatives face a backlash for failing to deliver or be rewarded for a "get Brexit done" promise?

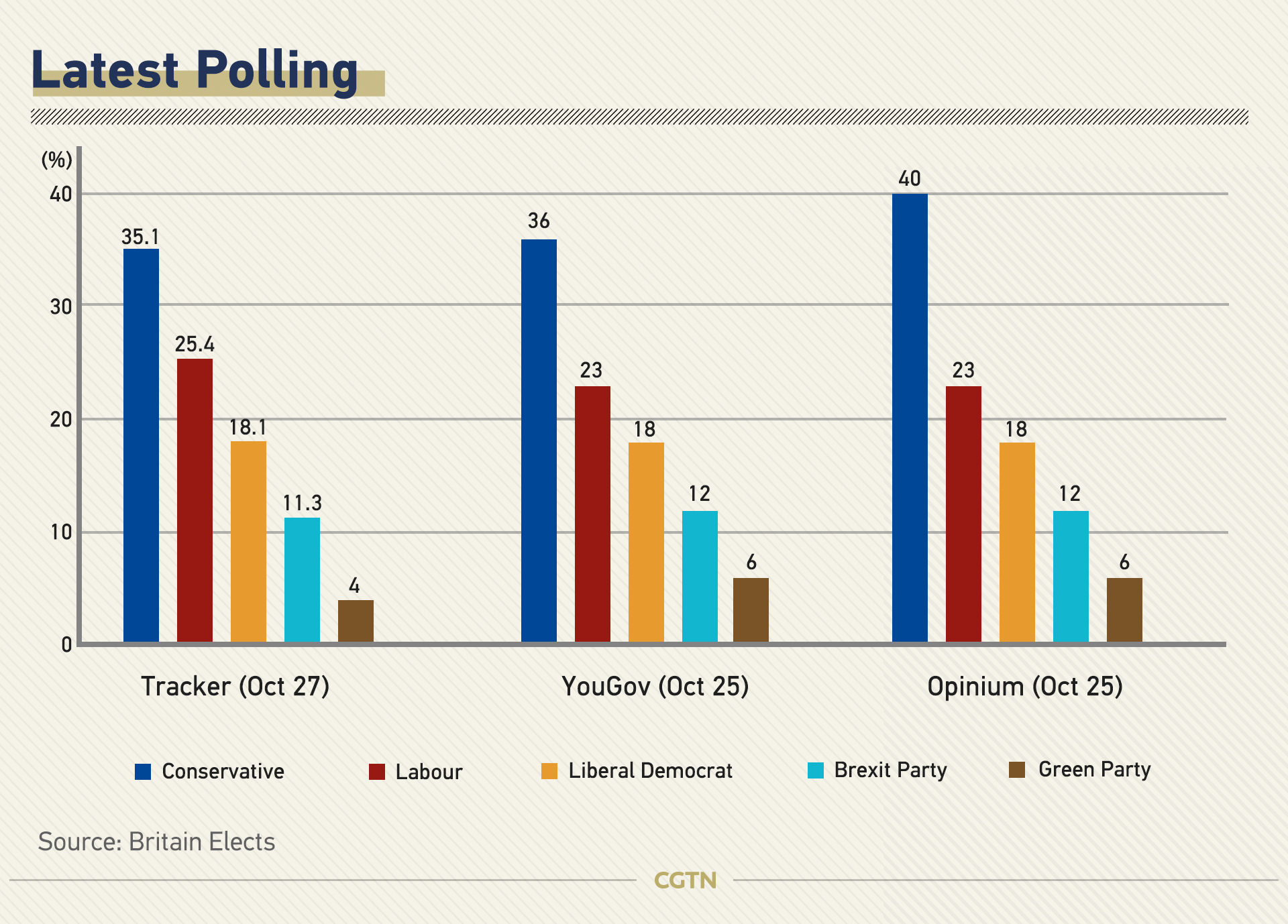

That suggests Johnson, even in the unlikely event the polls don't change as the campaign goes on, may struggle to translate the wide lead into a parliamentary majority. And it doesn't take into account Nigel Farage's Brexit Party, which could split the Conservative vote with its "pure Brexit" approach if it regains momentum.

Most polls give the Conservatives a big lead, but the double-digit advantage largely reflects their success in uniting Leave supporters. Remain backers are spread across several parties.

2. Labour's mixed messages

Labour wants to focus on its domestic policies, but it'll be tough for the party to escape the backdrop of Brexit. The parliamentary party is divided on the issue and the policy – a second referendum on a Labour-negotiated deal or Remain – isn't a simple sell to voters.

Read more:

MPs vote in favor of December 12 election

Graphics: Risky politics of a Brexit election

Party leader Jeremy Corbyn helped propel Labour to within two points of the Conservatives in the 2017 election however, having been 20 behind at the beginning of the campaign according to some polls, is confident his message and campaigning skills will bear fruit.

But the party has since been damaged by antisemitism allegations while splits over Brexit policy and the snap election are clear. More than 100 Labour MPs abstained from Tuesday's vote and 11 voted against in a sign of divisions and a lack of confidence.

3. Small parties, big disruption

The Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats finished first and second respectively in May's European Parliament elections with absolutist positions on either side of the Brexit debate. Neither are likely to replicate that success in a general election, but both have a route to a strong performance.

The Liberal Democrats have said they will cancel Brexit if elected as a majority government, a position likely to be watered down to backing a second referendum in a hung parliament.

Leader Jo Swinson will frame the election as a "last change to stop Brexit" and is confident of taking Remain-leaning seats from both major parties in southern England. The Lib Dems are also likely to pursue local pacts to boost other pre-Remain parties, like Plaid Cymru.

The Brexit Party – backing a no-deal – has been strangely quiet in recent weeks, and there have been persistent rumors that pacts could be agreed not to stand against Conservatives in some areas. If the Conservatives and Brexit Party do not strike an alliance, official or unofficial, leader Farage could scupper Johnson's hopes of winning northern Labour seats.

The Scottish Nationalist Party, meanwhile, is expecting to take seats from both the Conservatives and Labour while the Green Party could get a boost as part of a Remain alliance.

4. Voter volatility

Underlying the uncertainty of the election is the simple fact that British voters are becoming more unpredictable. Party identity is falling, with the votes likely to be shared across multiple parties.

Voter volatility has never been higher, according to British Election Study (BES). Across the three elections from 2010-17, 49 percent of British voters didn't vote for the same party. According to the BES that is partly due to weakening party ties but also what it calls "electoral shocks."

These are unique events or issues which have been hugely influential – from the 2008 economic crash to Brexit.

Brexit identity is now as important as party identity in determining a vote. That's part of the reason Labour's mixed message on Brexit is damaging and the Conservatives are set to launch a campaign that focuses heavily on Brexit, health, and law and order.

5. Christmas election

The election will be the first in December for nearly a century, and could hit turnout.

There have been concerns that poor weather, Christmas distractions, and students heading away from the areas they registered to vote could hit turnout.

However, election expert Professor John Curtice has suggested this may not be the case. The Brexit debate has energized British politics like nothing else in recent years, he argues, and the turnout in the December 1923 election was a very respectable 71 percent.