Unlike Ebola that affects tens of thousands of people, Hendra virus disease is quite low-key and only has seven human cases since its first outbreak in 1994. Despite limited infection, its mortality rate of over 50 percent can't be ignored. The fatal disease also has an intertwined history with horses.

In 1994, 21 stabled racehorses in Hendra, a suburb in Brisbane, Australia, had flu-like symptoms similar to respiratory diseases. Soon, 14 of them died and a new virus named Hendra was isolated from the horse's lung tissue. Two people who had closely taken care of these ill horses, a horse trainer and a groom, were infected. One died with severe pneumonia and the other survived an influenza-like illness.

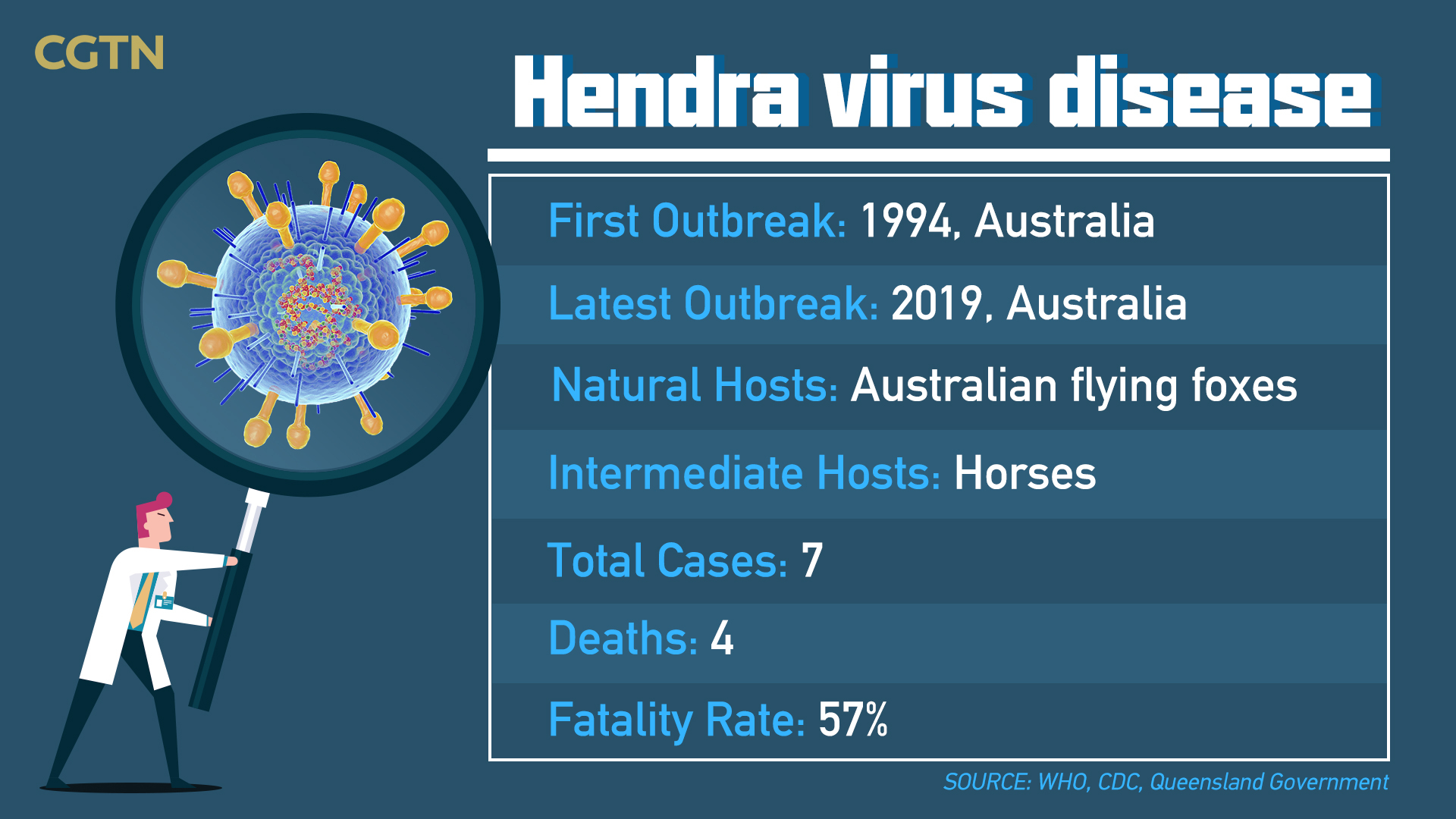

Facts on Hendra virus disease. /CGTN Graphic by Liu Shaozhen

Facts on Hendra virus disease. /CGTN Graphic by Liu Shaozhen

Apart from domesticated horses, dogs were also detected to be infected on the farm with ill horses in cases in 2011 and 2013, but showed no symptoms of illness. Under experimental conditions, more animals, such as cats, ferrets, hamsters, pigs, have all proven susceptible to Hendra virus infection.

Given that there is no neutralizing antibody in Queensland horses, the natural hosts of Hendra virus are not horses but others. Later, four species of Australian flying foxes were found to harbor the virus supported by serologic evidence, including the grey-headed flying-fox, the black flying-fox, the little red flying-fox and the spectacled flying-fox. The flying foxes have since then been recognized as natural reservoirs of Hendra virus.

A horse with its mouth wide open. /VCG Photo

A horse with its mouth wide open. /VCG Photo

Although the mechanism of bat-to-horse transmission is still a mystery, scientists speculated that horses might be infected from eating food contaminated by urine, saliva or other things from the flying foxes. According to a study made by researchers from the University of Sydney in 2017, the risk of Hendra infection was correlated with human intrusion into habitats of flying foxes.

Fruit bats (Pteropus alecto), also known as flying foxes, resting in a tree during the day in Queensland, Australia. /VCG Photo

Fruit bats (Pteropus alecto), also known as flying foxes, resting in a tree during the day in Queensland, Australia. /VCG Photo

Up to now, all of these outbreaks took place in the coasted and forested regions of northeast Australia. According to the World Health Organization, 53 Hendra virus disease incidents have been reported since 1994 and as of July 2016. Over 70 horses and seven humans were infected.

All infected humans are either veterinarians or horse trainers and have contracted the Hendra virus through direct contact with the blood, body fluids or secretions of ill horses, such as doing autopsies on horses. Patients suffer from fever, cough and fatigue. Some died from severe meningitis or encephalitis caused by the virus. Currently, no human-to-human, bat-to-human, dog-to-human transmission have been recorded.

A horse stands against the sun. /VCG Photo

A horse stands against the sun. /VCG Photo

About 'Epidemics and Wildlife'

Nowadays, 70 percent of epidemics or pandemics are connected with wildlife. As humans continue to consume game meat and encroach on the habitat of wild animals, these viruses carried by them are more likely to be transmitted to humans. In this series, CGTN shows you how wildlife are connected with each epidemic such as Marburg and Ebola.

For more:

How Ebola affects gorillas and chimpanzees?

How are African green monkeys linked to Marburg virus?

(Cover image via VCG, designed by CGTN's Chen Yuyang.)

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at nature@cgtn.com.)