It was the moment that signalled Kamala Harris's arrival in the Democratic presidential race: during a debate in June 2019, the California senator skewered former Vice President Joe Biden on busing, a scheme to combat racial segregation in U.S. schools in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

"There was a little girl in California... she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me," she said, going on to hammer a visibly shaken Biden.

Harris's jump in the polls did not last long, and the viral moment long threatened her chances at the vice-presidential nomination, with many in Biden's camp said to still be bitter about the exchange.

But it signaled she was not somebody to be trifled with, and it also demonstrated her lived experience: as a woman, a person of mixed race and a child of immigrants, all things that Biden is not but that represent key groups of Democratic voters going into November's presidential election.

Ticks all the boxes

Harris's nomination as vice president alongside Biden represents a series of historic firsts: the first Black woman and Asian American to feature on a major party's presidential ticket. She is also only the third woman to be nominated for VP.

In 2004, she became the first Black woman and first South Asian woman to serve as district attorney in San Francisco. Six years later, she was the first woman and first Black person elected as California attorney general. Making the jump to the U.S. Senate in 2016, she is now one of just two Black lawmakers and the first South Asian American in the chamber.

Read more:

Biden picks Harris: What does it mean for the U.S. presidential race?

Biden, Harris vow to 'rebuild' America in their first campaign

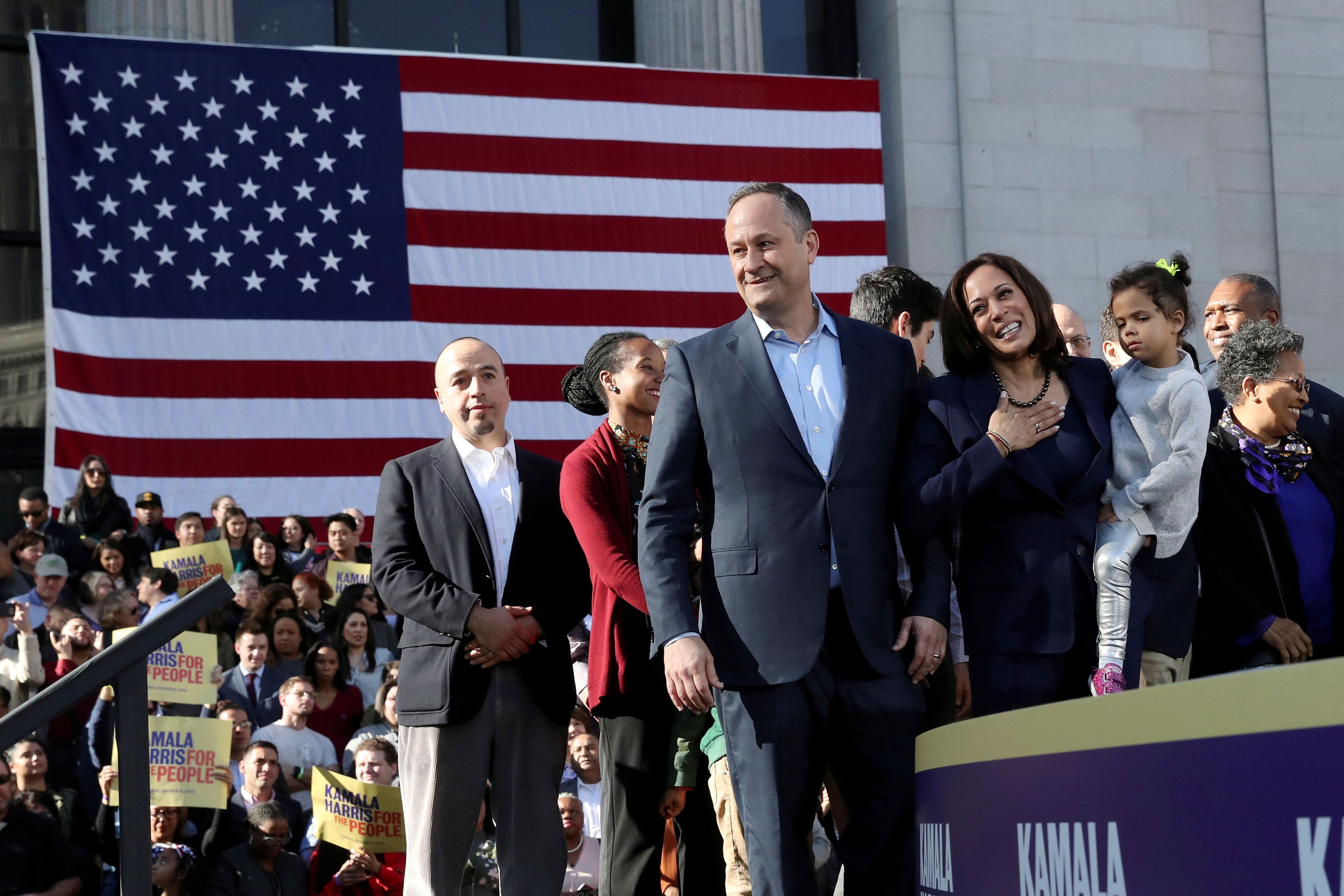

Senator Kamala Harris holds her niece Amara while standing with her husband Douglas Emhoff and her family as she holds a rally to launch her 2020 presidential campaign in her hometown of Oakland, California, January 27, 2019. /Reuters

Senator Kamala Harris holds her niece Amara while standing with her husband Douglas Emhoff and her family as she holds a rally to launch her 2020 presidential campaign in her hometown of Oakland, California, January 27, 2019. /Reuters

Harris's presidential bid petered out in late 2019 but once Biden became the presumptive nominee and promised to pick a woman as his running mate, she quickly made it to the front of a highly-qualified pack and stayed there.

Pundits repeatedly noted that the 55-year-old "ticks all the boxes": charisma, good debate skills, a great track record in elections and national political experience.

Former President Barack Obama also pointed to something else in a tweet welcoming her nomination on Tuesday: "Her own life story is one that I and so many others can see ourselves in."

Black. Indian. American.

Harris's mother Shyamala Gopalan came from Chennai, India and her father Donald J. Harris from Jamaica. The two met at the University of California at Berkeley where they were both PhD students, but divorced when Harris was seven. Raised by a working single mother along with her sister Maya, Harris grew up with different cultures, and also spent a few years in Canada.

"My mother understood very well that she was raising two Black daughters," Harris wrote in her autobiography "The Truths We Hold." "She knew that her adopted homeland would see Maya and me as Black girls, and she was determined to make sure we would grow into confident, proud Black women."

They were involved in the Black community and went to a Black church, but Gopalan also cooked Indian meals and took her daughters to India for visits. Kamala is an Indian name that means "lotus." Her middle name Devi, which she does not use, means "goddess."

A childhood picture of Kamala Harris featured in a Biden-Harris 2020 campaign ad posted by Joe Biden on Twitter. /CGTN screenshot

A childhood picture of Kamala Harris featured in a Biden-Harris 2020 campaign ad posted by Joe Biden on Twitter. /CGTN screenshot

This Indian side of Harris was relatively unknown until she launched her presidential campaign. She took it in her stride, even doing a video with Indian-American comedian Mindy Kaling where they cooked typical Indian dishes together.

Friends and colleagues note however that Harris has never tried to hide any aspect of her background, she just hasn't made a big deal of it: "I am who I am. I'm good with it. You might need to figure it out, but I'm fine with it," she was quoted as saying in a Washington Post profile last year. Asked how she would describe herself, she just said "American."

Harris's story reflects a diverse U.S. population that has long had little representation in the top echelons of government: 51 percent of people are women, 40 percent are non-white – Black, Latino, Asian or other – and about 13.5 percent are foreign born, according to U.S Census data.

Fighting for justice

Announcing her as his running mate on Tuesday, Biden described Harris as a "fearless fighter for the little guy." Obama said she had spent her career "fighting for folks who need a fair shake."

Harris herself likes to tell the story about how she already attended protests in a stroller. Her father Donald, later an economics professor at Stanford University, and her mother Shyamala, a breast cancer researcher, were both activists in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and Harris has credited them with inspiring her to seek justice and bring about change.

Instagram post by Kamala Harris. /CGTN screenshot

Instagram post by Kamala Harris. /CGTN screenshot

Her maternal grandmother back in India was already a community organizer who worked with domestic abuse victims and educated women about contraception. Her grandfather was a diplomat who, she says, "felt very strongly about the importance of defending civil rights."

In San Francisco, Harris tackled teenage prostitution and set up a reentry program to help young first-time drug offenders. As California attorney general, she managed to secure a 25-billion-U.S.-dollar settlement for homeowners affected by the foreclosure crisis and set up an online platform to make criminal justice data more transparent and improve police accountability.

In the wake of recent racial unrest in the U.S. over police killings of African Americans, Harris has called for bold police reforms, a national standard for use of force, independent investigations into excessive use of force by officers and greater police accountability.

In June, together with other colleagues in Congress, she introduced the Justice in Policing Act, banning chokeholds, mandating body cameras for law enforcement and establishing a national registry to document problematic officers.

But she has also faced criticism for her record as a prosecutor, her wavering stance on the death penalty, and policies like her crackdown on school truancy in San Francisco.

Democratic presidential candidate and former Vice President Joe Biden is greeted by Senator Kamala Harris during a campaign stop in Detroit, Michigan, March 9, 2020. /Reuters

Democratic presidential candidate and former Vice President Joe Biden is greeted by Senator Kamala Harris during a campaign stop in Detroit, Michigan, March 9, 2020. /Reuters

Critics, including in the Black community, have highlighted her failure to prosecute police killings during her time as attorney general and her lack of support for appointing special prosecutors to investigate police shootings. Many say she could have done more to tackle injustice and racism in the criminal justice system.

Defying labels

Cautious in her work and on the campaign trail – commentators have noted she tends to take small steps in dealing with a problem rather than rush in with major reforms – she has also shown she can be tough and relentless, as when she grilled attorneys general Jeff Sessions and William Barr, and Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh during Senate hearings.

She has been described as a "top cop," "tough on crime," but also as a progressive.

Kamala Harris has never fit neatly into one category or one box: from her diverse background to her career record, this will likely be a headache for conservatives who will struggle to maintain a clear line of attack against her.

Harris has often said she wants to change the system from within, rather than fight for justice from the outside. In a 2004 interview, she told the Los Angeles Times she wanted "to be at the table when important decisions are being made." In November's election, she will have a shot at one of the biggest tables there is.