Despite 2020 marking 70 years of diplomatic ties between China and India, the border tension over the past month has been heightened again.

Troops from the world's two most populous countries engaged in a physical clash in the Galwan Valley on June 15 with casualties reported.

Although the two Asian giants are not stranger to border incidents, it was the first time in decades that the border dispute turned deadly.

Read more:

Timeline: 70 years of China-India diplomatic relations

Why India-China border clashes matter

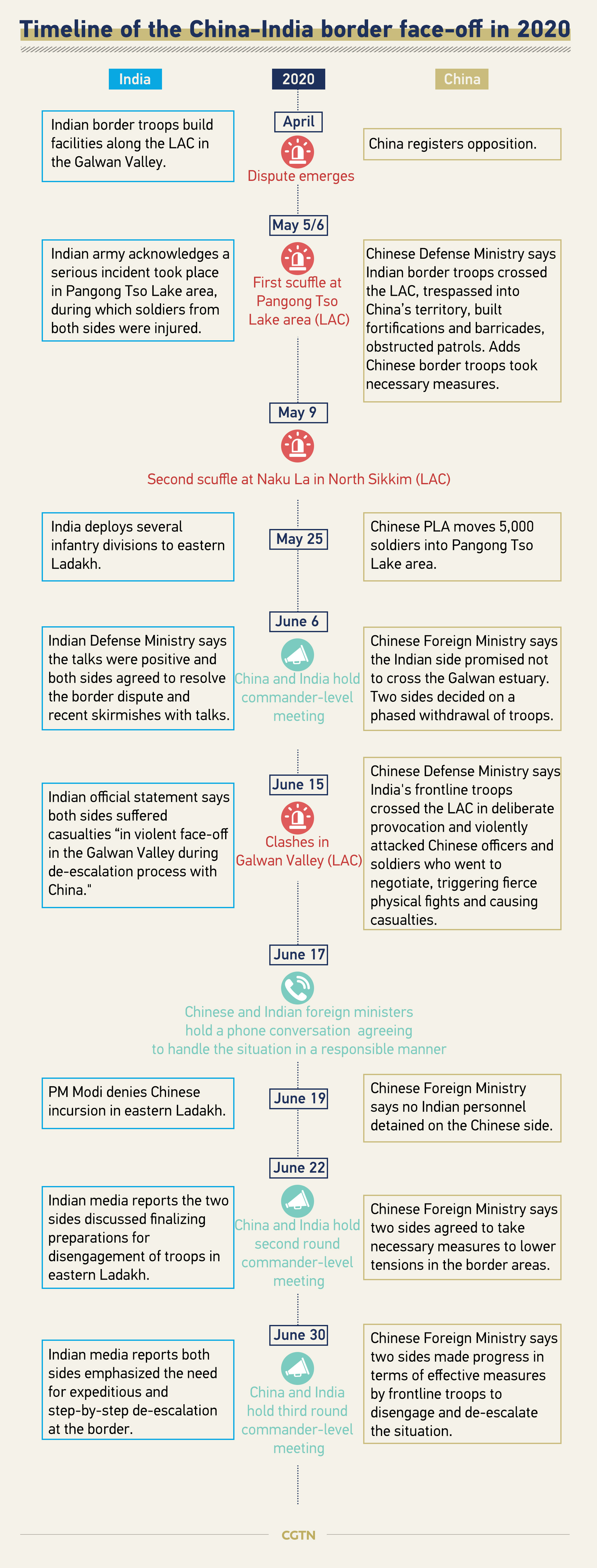

How has the standoff played out so far?

The border rift already appeared as early as April. According to the Chinese Foreign Ministry, Indian border troops started building roads, bridges and other facilities along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the Galwan Valley of eastern Ladakh, leading China to lodge representations many times.

Read more:

Chinese Defense Ministry blames India for border clash: it 'unilaterally' violates consensus

China urges India to thoroughly investigate border clash

The first standoff began in the early morning of May 6 at the Pangong Taso Lake area along the LAC, and a similar clash occurred in North Sikkim.

Media also reported that the two sides moved more troops to the eastern Ladakh region in the end of May.

To ease the tension, China and India held a commander-level meeting on June 6. Although they both claimed the talks were positive, violent clashes broke out on June 15.

As their official statements noted, China and India both accused each other of trespassing into the other's territory. The foreign ministers of the two countries held telephone talks on June 17, agreeing to cool down the tension.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a televised speech on June 19 openly denied China's incursion into Indian territory, adding no Indian military posts had been captured.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry later said another two rounds of commander-level meetings were held on June 22 and June 30 with positive progress achieved.

A conference room used for meetings between military commanders of China and India in 2009. /Reuters

A conference room used for meetings between military commanders of China and India in 2009. /Reuters

Why did the clash happen?

Indian news platform ThePrint pointed out the bone of the recent border disputes was India's series of infrastructure activities in the Galwan Valley, including road- and bridge-building.

Chinese and Indian experts meanwhile noted that the two sides' infrastructure projects in the border areas had become a catalyst for the border clash.

"This is an infrastructure game as far as the border areas are concerned," said Delhi-based defense analyst N.C. Bipindra.

Rong Ying, vice president of the China Institute of International Studies, said both countries have been strengthening their infrastructure construction for years, naturally affecting the balance of power between the two sides in the border areas.

As infrastructure can greatly improve the timely delivery of troop capabilities, such activities will result in suspicions over each other's strategic intentions, Jian Zhang, a Chinese foreign policy expert from UNSW Canberra at the Australian Defence Force Academy, explained.

A satellite image of the Galwan Valley in Ladakh, June 9, 2020. /Reuters

A satellite image of the Galwan Valley in Ladakh, June 9, 2020. /Reuters

Another major reason, according to some experts, is the link to the LAC. "They (Chinese soldiers) claim that it is their territory. Our claim is that it is our area. There has been a disagreement over it," Indian Defense Minister Rajnath Singh said when asked what happened at the border.

From China's position, Rong noted that although the boundary between China and India has yet to be formally delimited, the LAC "in general is clear".

Guan Peifeng, a professor from the China Institute of Boundary and Ocean Studies at Wuhan University, said that China is never the provocateur and that the Galwan Valley has been under China's actual control since the end of the 1962 Sino-Indian war.

According to Guan, the Indian side has never given up its Forward Policy: Last year the country abrogated Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which guarantees a "special status" to Indian-controlled Kashmir, and then established the so-called "Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir" and "Union Territory of Ladakh," which included disputed land between China and India, or India and Pakistan, in Indian territory.

India last November also published a new map that made the disputed Kalapani region along the Nepal-India border part of Indian territory, resulting in Nepal's strong opposition, Guan added.

Indian military personnel guard Bumla pass on the India-China border. /AP

Indian military personnel guard Bumla pass on the India-China border. /AP

Will Sino-Indian relations be impacted?

According to Indian and Chinese media as well as official statements, the two sides emphasized the need for reducing tensions during their third round of commander-level talks.

Read more:

Border dispute should not define China-India long-term relationship

Qian Feng, director of the research department at the National Strategy Institute, Tsinghua University in Beijing, said the meeting was a positive sign showing the tensions were cooling down.

Eurasia Group's South Asia analyst, Akhil Bery, said an amicable resolution to the dispute was likely as neither side wants to see an escalation in tensions.

Noting that the border issue is just one of the several disagreements between the two sides, Rong said China and India should properly handle it to prevent it from escalating into violent conflicts.

Prior to a final settlement, the two sides should make joint efforts to safeguard peace and tranquility along the border and not allow the issue to affect the overall interests of bilateral relations, he added.

Former Indian diplomats and academics also urged their country to stay calm and weigh the options when handling bilateral ties.

R Sudarshan, dean of the School of Government and Public Policy at O.P. Jindal Global University, argued in an opinion piece in The Hindu that it was not wise for India to focus on strengthening military might or boycotting Chinese imports when the country's economy was suffering from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Indian soldiers rest next to artillery guns at a makeshift transit camp before heading to Ladakh, June 16, 2020. /Reuters

Indian soldiers rest next to artillery guns at a makeshift transit camp before heading to Ladakh, June 16, 2020. /Reuters

"Attacking China as the enemy is not wise," Sudarshan warned, adding that in post-nuclear times, the only way to resolve disputes is through negotiations, as equal powers, with mutual respect.

Noting Beijing is New Delhi's biggest trading partner, with annual bilateral trade worth 92 billion U.S. dollars, former Indian Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran said India should avoid any "knee-jerk reactions" against China, as "it would be impossible for New Delhi to find alternative suppliers in the near future."

Chinese experts were optimistic about the prospects of bilateral relations, holding that the two sides abide by the consensus reached by the two leaders that China and India pose no threat but offer development opportunities to each other.

Zhang Jiadong, professor at the Center for American Studies, Fudan University, stressed that the two emerging powers' foreign strategy was stable. After the 1962 border war, there was no fundamental change in bilateral ties, nor did India change positions on important issues of principle, Zhang said.

Neither side intends to cause heavy casualties and the recent ones mainly resulted from objective factors like the high altitude, low temperature and dangerous terrain in the region, he added. A "mild problem" such as a cold or a slight head wound can lead to death under that environmental condition, Zhang said.

Beijing-based military analyst Zhou Chenming said the countries' leaders understood the possible consequences of the world's two most populous nations going to war.

"China and India must prioritize their economies as they are home to more than a third of the world," he noted.

Zhou also expressed confidence in a bilateral communication mechanism on border-related issues.

"Beijing and New Delhi have set up a five-level military communication mechanism – from brigades to chief commanders – for handling border disputes and hold regular meetings to share information," Zhou said.