As China wraps up its 13th Five-Year Plan (FYP) this year, all eyes are on the new FYP for 2021 to 2025 – a period that poses new domestic and international challenges.

A world of uncertainties

China issued guidelines on its 13th FYP in 2015, preparing the country for a "complicated" international environment, but no one expected at that time what the world would be facing.

Apart from the lasting confrontation between China and the U.S. over trade and technology, the COVID-19 pandemic has dragged down the global economy. The International Monetary Fund forecast a 2020 global contraction of 4.4 percent in its latest outlook released earlier this month.

Although China is the only economy in the world to show positive growth in 2020 so far, a struggling global market is casting a shadow over its growth prospects.

In a bid to maintain economic stability, China is working on what it calls "dual circulation," a new economic development pattern raised by China's top leadership in May, which aims at taking the domestic market as the mainstay while letting internal and external markets boost each other.

In line with China's efforts to boost domestic consumption, the dual circulation pattern is a natural choice for China – the world's second largest economy that is trying to reduce reliance on some key high-tech imports as well as its dependence on external demand to maintain sustainable growth amid the epidemic.

The task of deleveraging

China has been working on deleveraging to avoid systemic risks but the epidemic is making the job much harder. China's non-financial debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to sharply rise by 25 percentage points to almost 300 percent of GDP this year due to the credit stimulus and sliding nominal GDP, according to a research released in September by Wang Tao, chief China economist at UBS.

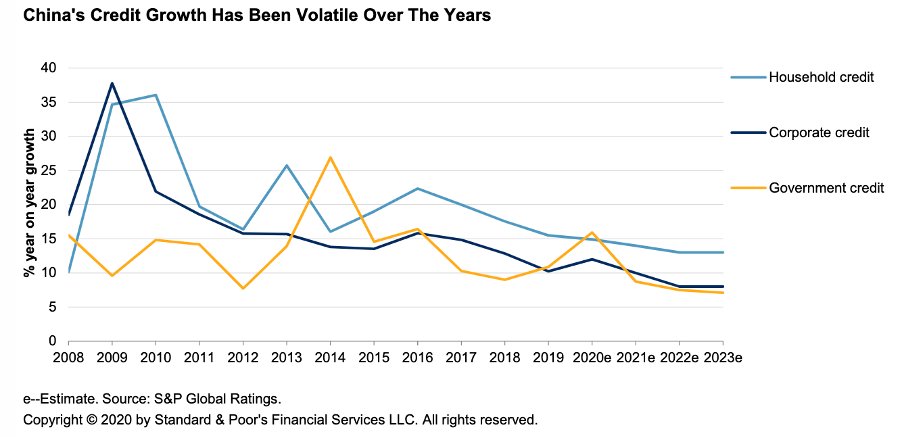

S&P made a similar prediction in June, saying total credit will rise this year but China has been reluctant to over-use debt to hit growth target.

China has been cautious about growth in corporate lending, especially in the debt-laden real estate sector.

Even amid the epidemic, China's policy makers made it clear that property bubble must be contained – no more easy loans for indebted developers.

China's central bank and the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development announced new financing rules for real estate companies in August, dubbed as "three red lines": 70 percent ceiling on liabilities to assets (excluding pre-sales), a net debt-to-equity ratio of under 100 percent, and cash holdings at least equal to short-term borrowing. Companies that step over these three red lines will be banned from more borrowing.

The debt restriction not only shows China's determination to cool down the property market and avoid speculation, but also weighs on local government income and even the broader economy.

Unbalanced development

China has opened the doors to suggestions from the public on the 14th FYP, allowing anyone to submit opinions or ideas online. Over 1 million submissions were received in two weeks starting August 16.

Livelihood issues, including an improved social security system, remain the top concerns of the Chinese people, according to data released by People's Daily.

With the elderly population (older than 65 years) jumping from only 8-9 percent during 2010-2015 to an estimated 14 percent in 2025, China's spending on elderly care and social insurance is expected to increase dramatically, requiring further reform of the pension system, the UBS report said.

Meanwhile, unbalanced development, including regional development gap and income inequalities, are obstacles to boosting domestic market and realizing urbanization.

For instance, last year, the total GDP of three provinces in northeast China, which suffered from weakening economy and population outflow, only accounted for about 47 percent of the GDP of China's richest Guangdong Province, according to official data.

Therefore, China has launched five regional development plans, involving Chengdu and Chongqing in southwest as well as the Greater Bay Area covering southern Guangdong Province and Hong Kong and Macao special administrative regions.

With continuous efforts in poverty alleviation, China's Gini Coefficient, the indicator of wealth gap, dropped to 0.465 in 2019 from the peak of 0.491 in 2008, according to data from CEIC.