05:53

When girls came back from their exam site for the Gaokao, China's annual college entrance exam, on June 8, Zhang Guimei hid in the office, refusing to come out. She wouldn't let reporters interview her nor have students bid her farewell.

This year, she sent 150 female students to college from a free all-girls high school she had founded in 2008 in southwest China's deep mountains. For the past 13 years, a total of 1,954 female students have graduated from this school, the first and only one of its kind in the country.

"To educate a girl is to change the destiny of three generations," Zhang said. The 64-year-old teacher from southwest China's Yunnan Province was presented with the July 1 Medal by Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee, at a ceremony in Beijing on Tuesday.

Read more: CPC holds ceremony to honor outstanding Party members

A fighter

Zhang was born to a family of ethnic Manchu minority group in northeast China's Heilongjiang Province in 1957. At the age of 17, she came with her sister to Yunnan as part of a team supporting the country's border regions. She met her husband in the pastoral city of Dali and worked as a teacher in a local school.

But the good times didn't last long. Her husband died of gastric cancer in the mid-1990s, five years into their marriage. Inconsolable, Zhang decided to leave this place with which she was too familiar. After her husband's funeral, she packed her stuff and went some 260 kilometers away to Huaping, an impoverished county nestled in the mountains.

There she witnessed dire poverty and the tragedies that it led to. "The destitution just sprawls in front of you, naked and straightforward," she recalled.

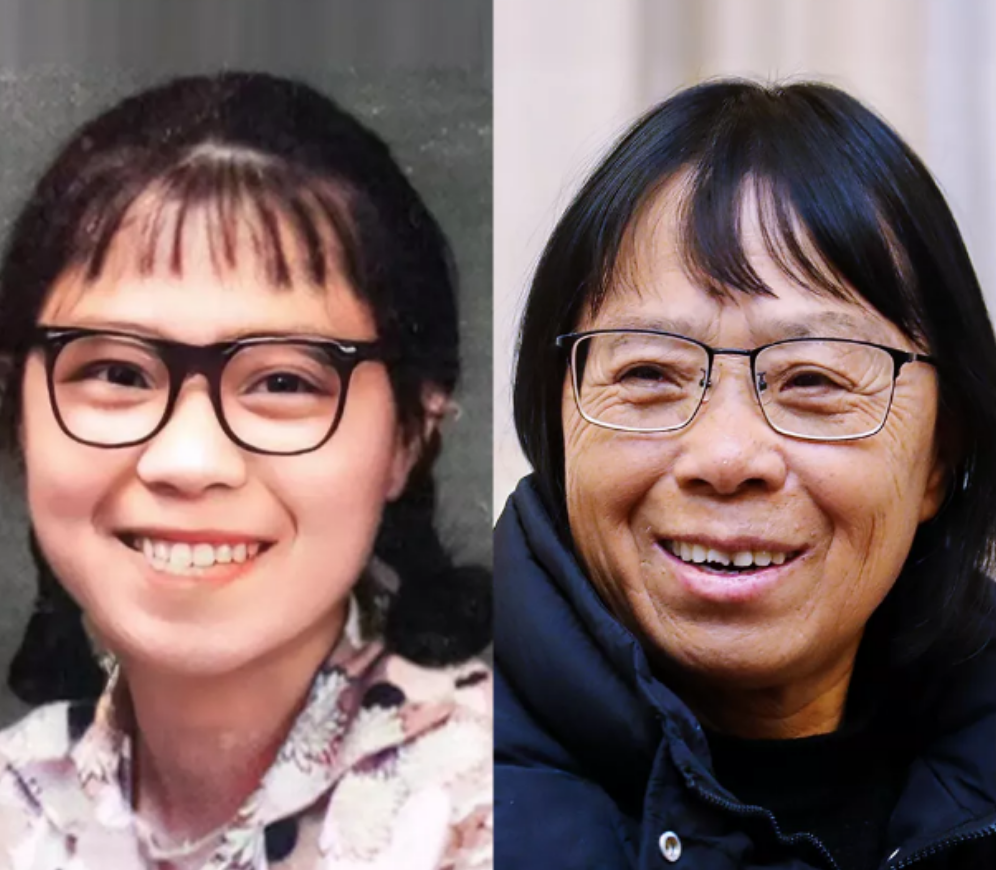

Zhang Guimei at the ages of 17 (L) and 64. /Xinhua

Zhang Guimei at the ages of 17 (L) and 64. /Xinhua

One day, Zhang saw a teenage girl sitting beside a shabby grass basket with a sickle in hand and staring at the opposite hilltop. She went to ask her if there was something wrong. The girl replied, "I want to go to school, but my parents are too poor to afford it. They have me engaged to be married, as they can get betrothal gifts (also known as "bride price") from the bridegroom." Zhang went to her home to persuade the parents, promising she could afford her tuition and living expenses, but to no avail.

Over those years, she discovered that many female students would just disappear after studying for a while. The reasons varied: to pay for the younger brother's tuition, the girl's parents would have her quit and return home for a job or work on the farm; the family received betrothal gifts, and the teenage girl would have to get married.

After becoming a "mother" at a welfare home for children in 2001, which she renamed as "Children's Home," Zhang learned more about the backgrounds of those young kids. Some of the mothers went to prison for killing abusive husbands while others died from childbirth due to medical misconceptions, leaving behind their newborns.

Zhang Guimei (R) visits a student's home in Huaping County, Yunnan Province, southwest China, July 2011. /Xinhua

Zhang Guimei (R) visits a student's home in Huaping County, Yunnan Province, southwest China, July 2011. /Xinhua

Over time, Zhang witnessed the gender gap in education up close in relatively poor rural areas. Urban and rural students already faced unequal access to quality education, and the traditional notion of male superiority only exacerbated rural girls' inferior situation. Some girls were even pulled out of class just before the college entrance exam because they had to provide for their brothers.

In 2002, Zhang came up with an idea which, to many, seemed crazy: to found a free high school for girls. That was a tough task. She had to raise money and hire teachers. Six years later, she founded the Huaping All-Girls High School. Given the rugged environment, however, nine of the original 17 teachers later resigned. With the goal of never letting a girl fall behind in schooling, Zhang often works overtime despite suffering from a bone tumor, aneurysm and chronic lung illnesses. Despite her debilitating health, she has walked to almost every household deep in the mountains, talking to the parents about the importance of education for girls.

To educate a girl is to change the destiny of three generations. A cultured, responsible mother won't let her daughter drop out of school.

- Zhang Guimei

Since the students there had weak academic backgrounds, the class day at this school is counted in minutes: five minutes to freshen up in the morning, 10 minutes to settle in for early study period, one minute to make it to the field for morning exercise. Students all pretty much have to run when going to classes, canteens and their dorms.

Zhang Guimei in a classroom with students in Huaping County, Yunnan Province, southwest China, July 2020. /Xinhua

Zhang Guimei in a classroom with students in Huaping County, Yunnan Province, southwest China, July 2020. /Xinhua

Women's education in China

Because of Zhang's endeavors to improve female education in China, more girls can change their destiny.

When the People's Republic of China wad founded in 1949, female illiteracy was much higher than that of their male counterparts. In the 1950s, the Chinese government launched campaigns that helped some 16 million females become educated.

In recent decades, wiping out illiteracy and improving the reading skills of women is regarded as one of the highest priorities in China, according to the government's guideline for helping the country's females. The female illiteracy rate for those above age 15 has decreased from roughly 90 percent in the early 1950s to 7 percent in 2019.

In 2021, China scored 0.973 in the Global Gender Gap Report released by the World Economic Forum (with a score of 1 being completely equal).