01:45

When recovery is unlikely, medical decisions usually fall on the shoulders of terminal patients' family members and doctors, who would find themselves caught in a dilemma. Unfortunately, their wish to let patients live as long as possible is not always shared by the patients who reckon the pain of keeping alive is too much to endure.

"I work in the geriatrics department and see many elderly patients who want to terminate their medical treatment," said Sun Yun, director of general medicine and geriatrics department at Shenzhen Shekou People's Hospital.

"They said that they wanted to have a say in their death and not to be a burden to their children," said Sun.

Things will change soon. Shenzhen became the first city on China's mainland to legally bind terminal patients' living wills after the city's revised medical regulation was passed in June.

The city's residents will have the final say in deciding how they will be medically treated during their last days of life, according to the new regulation.

Legal experts in China said that Civil Code, a national law that took effect on January 1, 2021, provides a legal basis for it. Article 1002 states that a natural person's life safety and dignity are protected by law and free from infringement by any organization or individual.

"The core of the dignity of life is a person's free will," said Xiong Beibei, a lawyer with East & Concord Partners Hangzhou. "Even if the consequence of refusing life-sustaining treatment is death, such dignity should be recognized by law."

"With the new regulation passed, hospitals and medical staff in Shenzhen do not have to worry about being held responsible when they choose to respect patients' living wills, avoiding possible disputes," Xiong said.

Xiong also pointed out that Shenzhen's bold exploration in the legal field can prepare for the protection of living wills in national laws in the future.

Why Shenzhen?

Shenzhen is a young city. By November 2020, only 5.4 percent of its population are aged 60 and above, while 3.2 percent are aged 65 and above, according to the latest national population census.

However, it is estimated that the city's registered population over the age of 60 will account for about 10 percent of its total population in five years. Moreover, the average life expectancy of its residents is expected to reach 84 by 2025.

An aging population and increasing longevity mean demand for end-of-life care will rise sharply in the years to come. Shenzhen has been pushing senior-friendly changes for the growing number of older adults, with the promotion of hospice care as a key aspect of these efforts.

Shenzhen, south China's Guangdong Province. /CFP

Shenzhen, south China's Guangdong Province. /CFP

In 2019, Shenzhen became a pilot city to promote hospice care, which provides services for reducing pain and addressing terminally ill patients' physical and psychological needs. By the end of 2021, nine municipal hospitals and 15 district-level medical institutions have built their teams for providing hospice care. Since then, nearly 3,000 patients have received such care.

When the Shenzhen Living Will Promotion Association was established last April, it was also tasked with promoting the cognition of hospice care as whether a patient needs this service at the end of life is clarified in a living will.

Seizing the chance to update the city's medical regulation, the association and the Shenzhen Municipal Health Commission worked together and made living wills legally effective last month.

However, some have raised ethical concerns such as whether living wills can be changed or canceled freely, and the definition of "incurable."

Li Ying, director of the association, held a meeting on July 10, arranging detailed preparations for when the new regulation will be enacted on the first day of 2023.

Li highlighted several tasks during the following months, such as producing a formal version of a living will document and helping decide the procedures of notarizing and managing living wills.

From taboo to hot topic

Over 30 countries and regions have made living wills or advance directives legally binding worldwide. However, the United States was the first to establish laws related to living wills.

It took many years for the living will mechanism to take root in China. Even today, death is rarely discussed openly in China as it is still seen by many as a social taboo, especially among the nation's senior population.

Only about 20,000 people registered their living wills through the website Choice and Dignity, which was built in 2006 to promote death with dignity, hospice care and living wills in China. Based on the website's efforts, the first living will promotion association in the mainland was founded in Beijing in 2013.

"Not all people are comfortable talking about death. In most cases, young people are more open to such discussions," said Wang Ying, director of the Beijing Living Will Promotion Association.

During the past two decades, more than 20 universities in China have set up courses on death education. But compared to a large number of students, access to death education in China is still in shortage.

Wang also pointed out that living wills need to go hand in hand with hospice care. One obstacle to promoting living wills is to find hospitals and doctors that are able to perform the wishes in a living will.

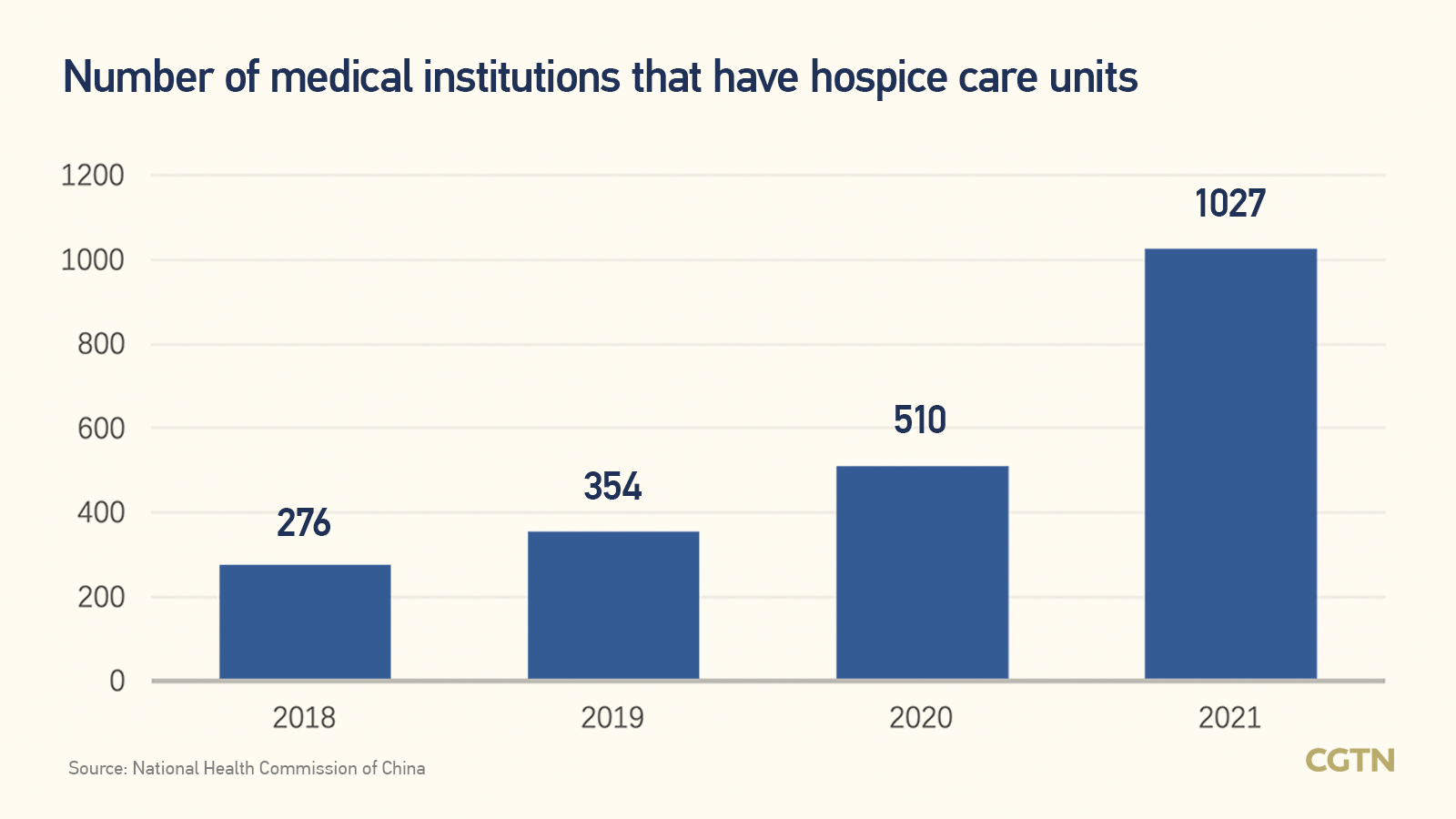

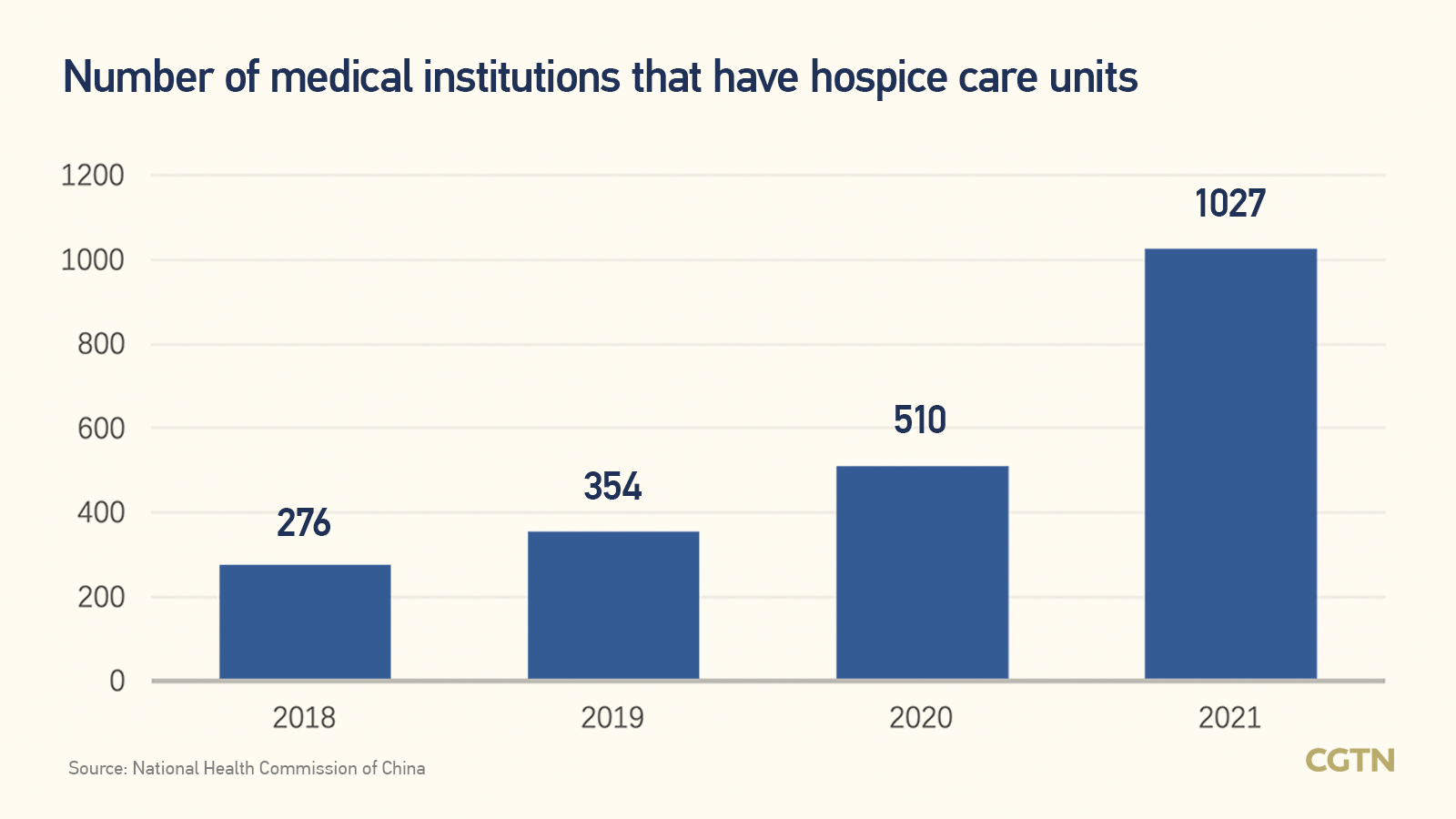

With national guidelines and standards in place, the promotion of hospice care has been rolled out in pilot cities in China since 2016. Data shows that 1,027 medical institutions nationwide have hospice care units by the end of 2021, according to the Statistical Bulletin on Health Development in China released last Tuesday.

Living wills pave the way for getting hospice care which is an important resort to minimize suffering as death approaches and improve the quality of death.

"It is the duty of medical science to let patients leave the world in the most comfortable way during their last days of life," said Gu Jin, director of Peking University Shougang Hospital.

The hospital is one of the 30 medical institutions in Beijing that have hospice care units. By April, more than 2,000 patients with terminal cancer received hospice care services in the hospital.

Text by Du Junzhi

Video edited by Yang Yiren

Infographic designed by Yu Peng