Politics

19:23, 29-Jul-2017

Why did the DPRK fire two ICBMs within a month?

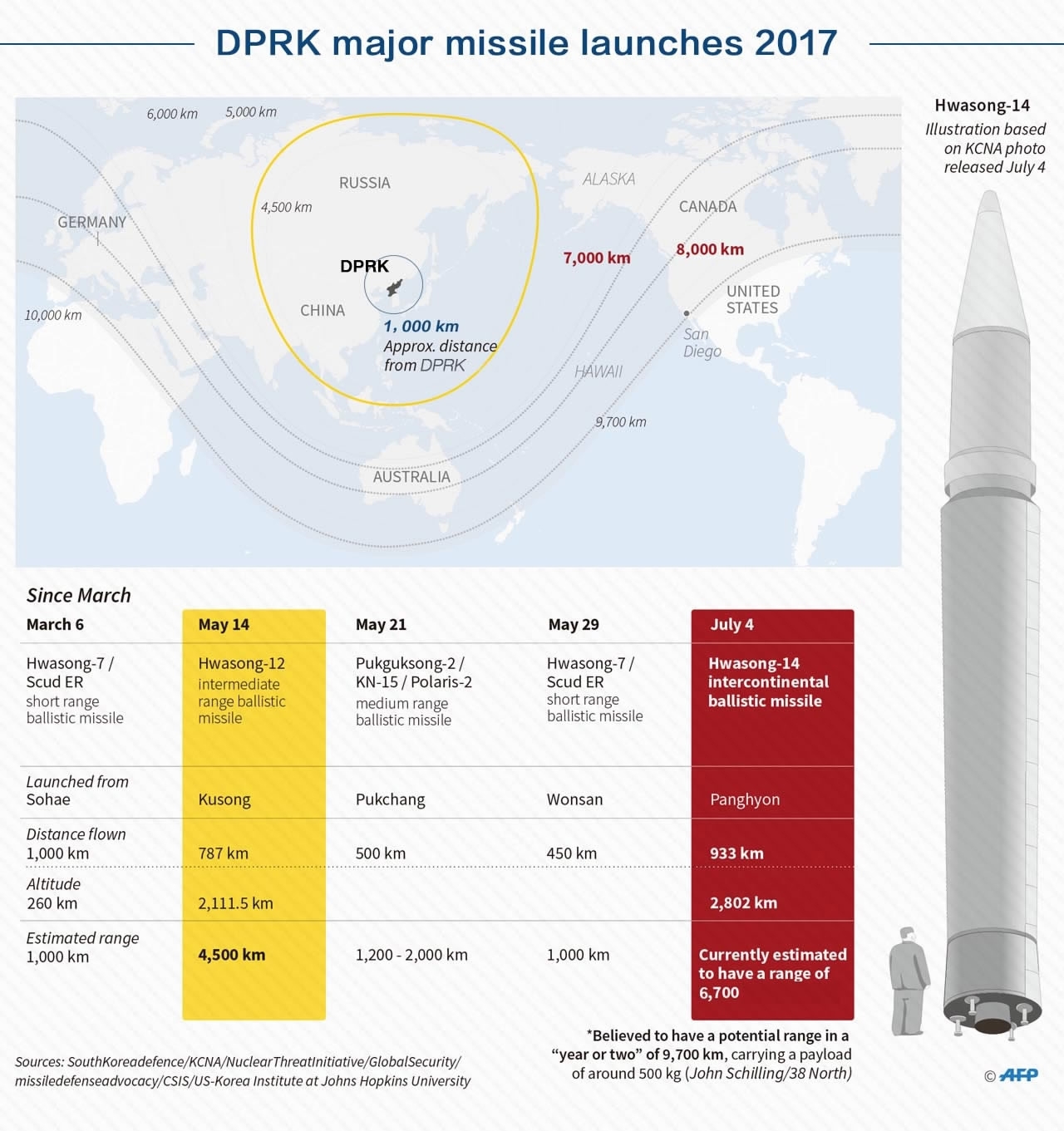

After successfully launching its first ever Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) on July 4, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) test-fired a second similar projectile late on Friday night, ignoring strong opposition from the international community and repeated calls for Pyongyang to engage in dialogue.

But why is the DPRK so determined to carry on with its missile and nuclear program, risking more sanctions and pressure from the United States?

The answer lies in the small country's deep-rooted sense of insecurity, which stems from both the devastating 1950-1953 Korean War and the escalated tension on the Korean Peninsula in recent years.

The DPRK's leader Kim Jong Un (R1) guides the second test-fire of ICBM Hwasong-14. /Reuters Photo

The DPRK's leader Kim Jong Un (R1) guides the second test-fire of ICBM Hwasong-14. /Reuters Photo

'Stern warning'

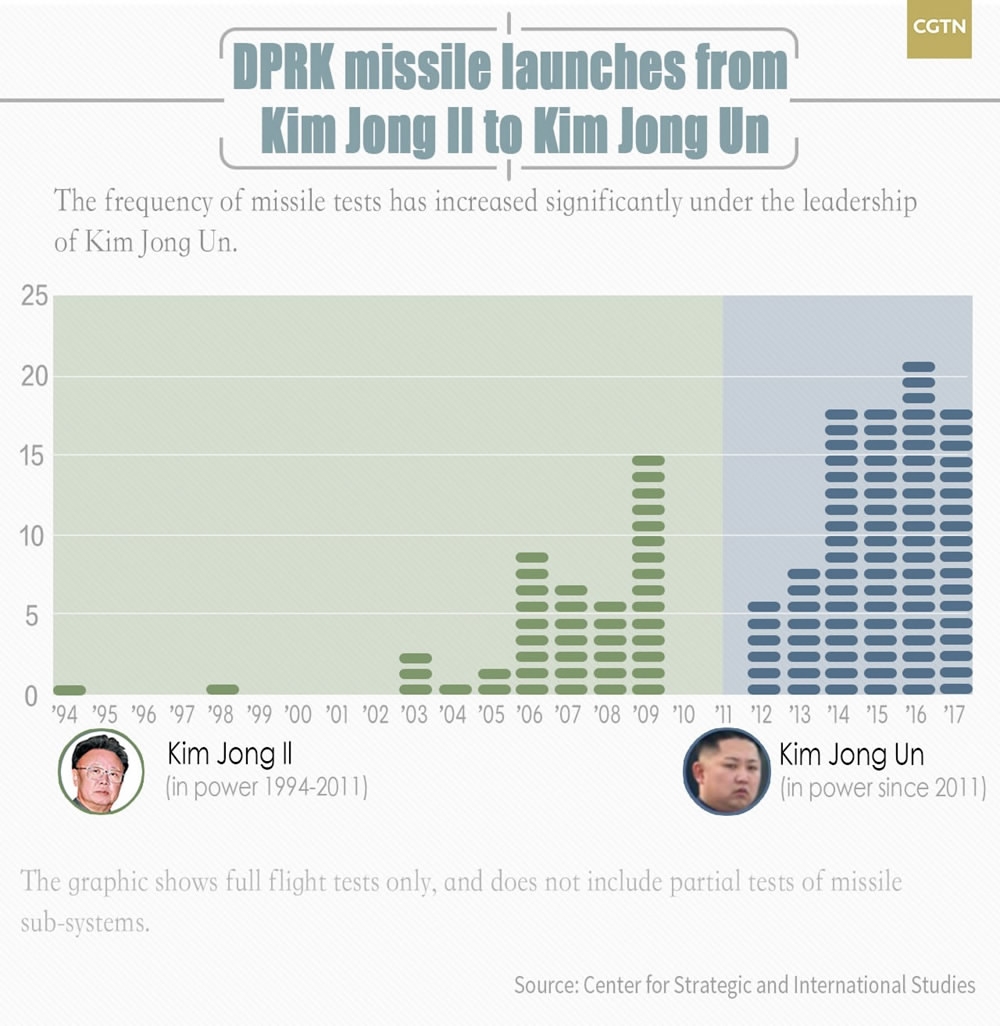

The world was not surprised by the DPRK firing two missile in less than four weeks. The country has already fired 18 missiles in 12 tests since February.

Both tests took place a day after the country marked important festivals: on July 3, the DPRK celebrated the Day of Strategic Force and on July 27 it marked the Day of Victory.

What made the two launches remarkable was that the projectiles were long-range missiles which Pyongyang said can strike the US mainland. The Hwasong-14 tested on Friday – the same model the DPRK launched on July 4 – could put New York City in its range, according to Melissa Hanham, senior research associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

The DPRK was straightforward about its intention, saying that the successful test of a second Hwasong-14 ICBM was a "stern warning" to the US, the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) reported on Saturday.

The launch aimed to test the longest range of the Hwasong-14 ICBM carrying a heavy nuclear warhead as well as the weapon system, according to KCNA, which added that the launch had "successfully tested re-entry capabilities" of the missile.

The country's leader Kim Jong Un said, "The test also confirmed all the US mainland is within our striking range".

Kim stressed that the launch, which unusually took place at a previously unknown site at night, proved that the DPRK could launch ICMBs at any place and time.

DPRK's "unswerving" efforts to test ICBMs were "stern warnings" to the US, the report said, adding that the US would pay a heavy price if it invaded the DPRK.

CGTN Graphic

CGTN Graphic

Security concerns

Why does Pyongyang keep sending "stern warnings" to Washington? Insecurity, perhaps, and a belief that continuously flexing military muscles will be a deterrent against the US.

In a statement shortly after the launch on July 4, DPRK's Foreign Ministry said now "the US would find it more difficult to dare attack the DPRK," and stressed that "this is the only way to defend oneself and safeguard the dignity of the nation in the present hostile world where the law of the jungle prevails."

Facing foes with military might such as the US and its regional allies the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Japan, the DPRK government believes that in order to survive, it must get strong enough to threaten the American heartland.

In an analysis published by The Washington Post on Friday, foreign affairs commentator Adam Taylor said the DPRK would not give up its nuclear weapon and ICBM programs, especially as it witnessed what had happened to Libya's Moammar Gaddafi and Iraq's Saddam Hussein – both were overthrown and killed after abandoning their weapon ambitions.

To make matters worse, the US is deploying a powerful Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile system in the ROK, a controversial move Washington claims is aimed to protect Seoul from Pyongyang's threat but is strongly condemned by China and Russia.

With two THAAD launchers already deployed in the country, ROK President Moon Jae-in on Saturday ordered his aides to consult with US counterparts about the deployment of four more mobile THAAD launchers.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang reiterated China's opposition to the move on the same day, saying that the deployment seriously undermines the regional strategic balance and security interests of regional countries including China.

A THAAD interceptor is launched during a successful intercept test. /Reuters Photo

A THAAD interceptor is launched during a successful intercept test. /Reuters Photo

In a commentary published by China Daily last year, Guo Xinning, vice president of the College of Defense Studies at China's PLA National Defense University, said the deployment of THAAD in South Korea would tip the "already fragile" strategic balance on the Korean Peninsula more in favor of the south and further intensifies DPRK's sense of insecurity, resulting in accelerated advancement of its nuclear weapon program.

His words are being translated into reality.

China has urged the US to address the DPRK's "legitimate security concerns" on many occasions, but Washington has neither stopped the THAAD deployment nor suspended military drills near the peninsula.

Historical roots

Friday's ICBM test was conducted one day after DPRK's Day of Victory, a public festival to mark the date when the armistice of the Korean War was signed 64 years ago.

For the DPRK, the wounds of the war, which claimed millions of lives and all but leveled the peninsula, are yet to heal.

"Its legacy of destruction lives on," CNN's Joshua Berlinger wrote on Friday, trying to explain why the DPRK "still hates the United States."

In the words of former US Air Force commander Gen. Curtis LeMay, the Americans "burned down every town" in the DPRK and "some" in the ROK. After the armistice was signed, people in the DPRK "stayed amid the ruins of the battle – their entire infrastructure decimated, their towns and cities completely obliterated."

During the three-year war, US planes dropped approximately 635,000 tons of explosives on the DPRK (more than during the entire Pacific theater of World War Two), including 32,000 tons of napalm, according to historian Charles Armstrong.

The large-scale air campaign has been viewed as the "original sin" of the US by the DPRK, Berlinger noted.

CGTN Graphic

CGTN Graphic

The DPRK, which relied on its "main backer" – the Soviet Union during the Cold War, "felt extremely insecure" with the decline and disintegration of the USSR in early 1990s, said Fu Ying, chairperson of the Foreign Affairs Committee of China's National People's Congress.

In a strategy paper written for the John L. Thornton China Center of American think tank Brookings Institution earlier this year, Fu indicated that the rapid economic growth in the ROK also added to the anxiety of the DPRK.

After failed negotiations with successive US administrations, Pyongyang is determined to possess nuclear weapons to ensure its security.

US holds the key

China, which has opposed nuclear and missile tests carried out by the DPRK and committed to the goal of the denuclearization on the peninsula, has proposed that the DPRK suspend its missile and nuclear activities in exchange for a halting of large-scale military exercises by the US and ROK, paving the way for dialogue.

But the US has made it clear that the DPRK must abandon its nuclear weapon program before the resumption of negotiations. Meanwhile, US President Donald Trump wants China to put more pressure on the DPRK to break the deadlock.

However, Fu said it is the US that holds the key to the issue, stressing that China cannot make the DPRK stop its nuclear weapon program.

China has been working hard to play its role both as a mediator and a party to UN sanctions, but it does not have the leverage to force either the US or the DPRK to address each other's concerns, she added.

Fu explained the DPRK sees the US as the source of threat to its security and that China does not hold the key to its security concerns.

In that sense, where the DPRK situation heads will depend on how Washington addresses Pyongyang's deep-rooted security issues. Beijing will continue to help, but it does not have what it takes to make it or break it when it comes to the DPRK nuclear issue.

Related stories:

SITEMAP

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3